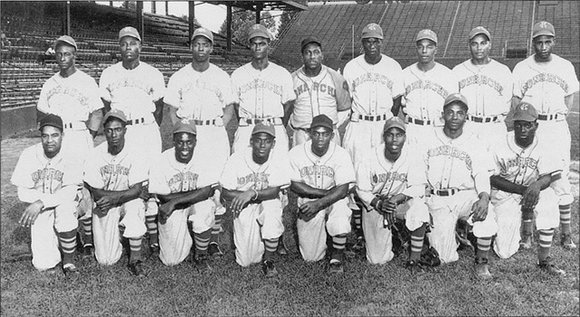

Kansas City Monarchs

World Series matchup takes us on trip down memory lane

Fred Jeter | 10/28/2014, 6 a.m.

For most of the first half of the 20th century, professional baseball was divided into two distinctly separate divisions.

There was the all-Caucasian version centered in New York City, with the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants.

Meanwhile, the hub of all-black baseball generally was considered Kansas City, Mo., where the Monarchs were a decades-long force in the Negro Leagues.

As this year’s 110th World Series continues, Kansas City again will be a focus as the Kansas City Royals take on the San Francisco Giants.

The Kansas City Royals have 10 players of color on their 25-man roster. The San Francisco Giants have nine players of color.

Black and brown athletes have graced baseball’s brightest stage since 1947, when Jackie Robinson crossed the racial divide with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Until Robinson’s breakthrough, however, players of color, including African-Americans, were confined to teams such as the Monarchs, who thrilled their own loyal fan base.

With Kansas City baseball in bold headlines today, let’s take a stroll down memory lane and examine a time the Monarchs put K.C. baseball on the map.

Test of time: The Kansas City Monarchs were the longest enduring Negro League franchise. Starting in 1920, the team continued operations until 1965. After 1950, though, black teams were reduced to barnstorming, more for amusement — Harlem Globetrotters-style — than pure competition.

Trophy case: The Monarchs won 13 titles in the Negro National and American leagues, from 1923 to 1955. They won the first Negro World Series, which was played in 1924 in Kansas City, and won again in 1942. The Negro World Series was held from 1924 through 1927 and from 1942 through 1948.

Let there be light: In 1930, the Monarchs introduced their own portable lighting system that they carried with them on the road. This was five years before white baseball teams began playing after dark.

This is reflected in the biopic, “42,” about Robinson. An early scene in the movie features Robinson playing for the Monarchs in extremely dim lighting.

Farm club: The Monarchs were among the few Negro League franchises with their own farm club — the Monroe, La., Monarchs. Alumni include Hilton Smith, now in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Star power: Many of the all-time greatest Negro League players suited up for the Monarchs. The list includes Hall of Famers James “Cool Papa” Bell, Satchel Paige, Bullet Rogan, Robinson and Ernie Banks.

After 1947, the Monarchs sold 25 players — the most by any Negro League outfit — to the big leagues, mostly for $5,000 each. Banks drew the largest check, $20,000, when he was sent to the Cubs in 1953.

Monarch Elston Howard became the first black New York Yankee in 1955.

Buck O’Neil played for the Monarchs from 1938 to 1955 (interrupted by World War II) and was manager of the team from 1948 to 1955, winning three pennants.

The Cubs hired O’Neil as a scout in 1955, and made him the first black coach in the majors in 1962.

The Monarchs played at Blues Stadium (17,476 seats), which it shared with the white minor league Kansas City Blues.

Come take a look: Founded in 1990, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum (NLBM.com) is in Kansas City at 1616 E. 18th St., in Kansas City’s historically black Vines District.

Strike up the band: Back in the day, Kansas City was known as much for its music with black cultural roots as its baseball. The Kansas City Jazz Museum is in the same complex as the baseball museum, which is within home-run distance of “12th Street and Vine,” mentioned in the song “Kansas City.”

“Kansas City” has been recorded by more than 300 artists, originally by Little Willie Littlefield. Wilbert Harrison later made it into a hit. Little Richard, James Brown and even The Beatles also recorded the tune.

The song’s lyrics below point to how the Midwest city was a prized destination for so many looking for a good time:

“Well I might take a plane, I might take a train, but if I have to walk I’m going just the same. I’m going to Kansas City. Kansas City here I come.”