When Freedom Came, Part 3

Elvatrice Belsches | 4/9/2015, 4:22 p.m. | Updated on 4/10/2015, 4:56 p.m.

The Free Press presents a three-part installment chronicling the African-American experience during the liberation of Richmond in April 1865 and the final days of the Civil War.

Once Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant forced the surrender of Confederates under Gen. Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, Richmond was nearly overrun by men and women flocking to its borders.

Former soldiers — both black and white — swept into the city looking for their families. Thousands of other black people also arrived, trying to locate loved ones from whom they were separated and sold in Richmond’s massive and nefarious slave trade.

Richmond’s pre-Civil War population of roughly 12,000 enslaved people, as counted by the 1860 Census, swelled to include at least 20,000 black people in Richmond and the separate town of Manchester on the south bank of the James River by summer 1865.

Directly after Richmond’s liberation by Union troops on April 3, 1865, a provost marshal’s office was set up downtown to establish order, protect residents and oversee the administration of the city. The Richmond headquarters for the federal Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, more commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, also was set up near what is 10th and Broad streets today.

According to the National Archives, the Freedmen’s Bureau was established nationally on March 3, 1865, under the auspices of the U.S. War Department, with the intent of assisting white and black people with clothing, food rations, labor contracts and educational opportunities.

Freedmen’s courts were set up in various jurisdictions throughout the South to hear cases involving newly freed black people. The bureau also undertook the task of legalizing and recording thousands of marriages entered into by enslaved men and women prior to the end of the Civil War.

The widespread elation and joy accompanying the arrival of Union troops in Richmond and the subsequent Confederate surrender at Appomattox was soon supplanted by sorrow at the news of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

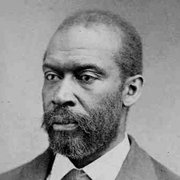

Thomas Morris Chester, the only known black reporter to cover the Civil War for a major daily newspaper, the Philadelphia Press, chronicled the scene in Richmond.

“The dreadful intelligence from Washington was received in this city yesterday about noon. The first report came that he [President Lincoln] was dead, which smote the hearts of the loyal people with deep sadness, but they resolved not to credit it. But soon the official confirmation removed all doubts, and the people were overwhelmed with profound grief…” Thomas Morris Chester, April 17, 1865

Black Richmonders’ hopes of brighter days in freedom dissipated. They also were confronted with new harsh realities, including the implementation of a new system requiring them to show special passes to move around the city and a provost marshal’s office that was indifferent at times to their complaints.

African-Americans walking the streets without a pass were subject to arrest. More than 800 black men, women and children were arrested and put in jails and former slave pens in Richmond during the first two weeks of the pass requirements, according to one record.

Affidavits filed by African-Americans with the Freedmen’s court in Richmond provide a sobering view of the abuses they endured. Men, women, elderly people and children were verbally and physically assaulted by former Confederates as well as federal guards under the provost marshal’s office. They reported being beaten and robbed. Their homes were ransacked and sometimes burned. People attested in depositions to hearing the screams of black women as they were sexually assaulted in holding cells.

Life for many black people was chaotic initially with rampant crime, victimization and new rules for arrest. Laws commonly known as the “Black Codes” were made more severe by state and city lawmakers to further subjugate the newly freed masses. One such law made black people subject to arrest and eligible to be hired out if they were unemployed.

Freedom under these circumstances was almost untenable.

“It can no longer be disguised that the military rule of this city has been squared … in accordance with the feelings of the rebels, until it has culminated in the reinstatement of one of the greatest secessionists as mayor of this city, and the reappointment of his rebellious police …” Thomas Morris Chester, June 12, 1865.

At a mass meeting at First African Baptist Church, as many as 3,000 men decided to prepare a list of grievances about the military rule and to compile the affidavits attesting to the outrages inflicted upon them.

Their concerns had been met with indifference when they took their grievances to the provost marshal’s office. So they raised money and sent a five-person delegation to Washington, D.C., to meet with President Andrew Johnson on June 16, 1865.

The meeting was reported in newspapers across the country and recorded in “The Papers of Andrew Johnson.” The delegation of black men was comprised of Fields Cook, a preacher and community leader who would run for Congress in 1869; William Williamson; William T. Snead; and the Rev. Richard Wells, who would pastor both Manchester Baptist Church — known as First Baptist, South Richmond today — and later Ebenezer Baptist Church in Richmond. The fifth delegate, who reportedly read the petition before President Johnson, was Mr. Chester, the Philadelphia Press correspondent.

The delegation outlined abuses occurring in Richmond and requested a change in who was governing the city. They also lobbied for the right of Richmond’s black churches to appoint their own pastors and the right to own the church edifices.

According to accounts, President Johnson listened attentively. He also informed the group that personnel changes among those overseeing the city and handling matters of citizen welfare and complaints were under review. He also informed them that he would do all within his power to assist them. The pass system later was dropped.

Black leaders in the city greeted education as the key to sustained uplift by black people from slavery. The Freedmen’s Bureau and black Richmonders wasted little time in formally starting schools for the newly emancipated.

Although some black people were literate prior to freedom, they could freely engage in learning after the Civil War. The freedmen themselves and New England schoolteachers were some of the first to formally open schools in Richmond.

Lucy and Sarah Chase, white sisters from Massachusetts, had moved to Tidewater during the Civil War and helped with clothing, food, housing and education for many black people who had escaped slavery and fled to Fort Monroe and Norfolk. Following Union victory at Appomattox, the sisters moved to Richmond to do the same for newly freed black people.

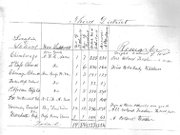

A letter Lucy Chase wrote, ironically penned on the back of a blank slave bill of sale from the slave trading firm R.H. Dickinson and Brother, tells of the extensive and significant desire and motivation of black people to learn.

“My Dear Miss Lowell — Miss Stevenson has already told you that we gathered the children in different churches on the 15th of April and opened informally at that time. Yesterday, the 19th of April, my sister and I formally opened school in the 1st African Church (the largest church in the city…) We had more than one thousand (1000) children and seventy-five adults, and found time, after disciplining them, to hear the readers, to instruct the writers, and to teach the multitude from the blackboard. Again today, we had a huge school of nine hundred … Four churches are in use here, and fifteen hundred children are already in attendance …” Lucy Chase, April 20, 1865

Some of the earliest teachers in the Freedmen’s Bureau’s schools in Richmond were black Richmonders. Among their ranks were James Bowser, husband of educator Rosa Bowser; Otway M. Steward and Peter Woolfork, who later would operate and edit the Virginia Star newspaper; and Joseph E. Farrar, a leading contractor who later would serve on the Richmond City Council.

Perhaps the greatest legacy of the Freedmen’s Bureau is its major impact on public education systems throughout the South. Virginia did not have a public school system before the Civil War. The state would establish one in 1870 as a prerequisite for officially rejoining the Union in good standing. Richmond’s public school system began in 1869.

The necessary infrastructure for establishing a statewide system of public education was developed in large part under the leadership of Ralza Morse Manly, a former Union army chaplain during the war. Rev. Manly oversaw the Freedmen’s Bureau’s educational efforts in Virginia through most of the bureau’s tenure in the state.

Many of the nation’s early historically black colleges and universities trace their beginnings to the Freedmen’s Bureau and efforts early on by religious and philanthropic groups working with societies to aid the freedmen. Among them are Virginia Union University, Hampton University, Howard University and Shaw University.

The Freedmen’s Bureau also recognized that secondary schools were needed to prepare black teachers. One of the most successful of these was Richmond Colored High and Normal School, located initially at 6th and Duval streets and later relocated to 12th and Leigh streets. Founded in 1867, Colored Normal, as it was called, taught the classics and was based on the New England model of education. Renamed Armstrong High School about 1909, the school was so successful that Northern journalists would travel to Richmond to write about its teachers and students.

Among Colored Normal’s attendees and graduates were African-Americans whose lives and contributions would have important impacts on the city, state and nation in areas of business, medicine, law, politics and education. Early graduates included educator and organizational leader Rosa Bowser, for whom the former library building on Clay Street that serves as the home of the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia was named; Dr. Sarah G. Jones, co-founder of what would become Richmond Community Hospital and the first female in Virginia to pass the state medical boards and be granted a license to practice medicine in the state; John Mitchell Jr., longtime editor of the Richmond Planet newspaper; Maggie L. Walker, pioneering female bank president, educator and organizational leader; and Marietta L. Chiles, who spent nearly 40 years teaching freedom’s first generation of black students in public schools in Richmond.

From their new freedom, black Richmonders would couple their educational attainments with a profound collectivism to transform Richmond into an epicenter of black commerce, educational excellence and social justice leadership.