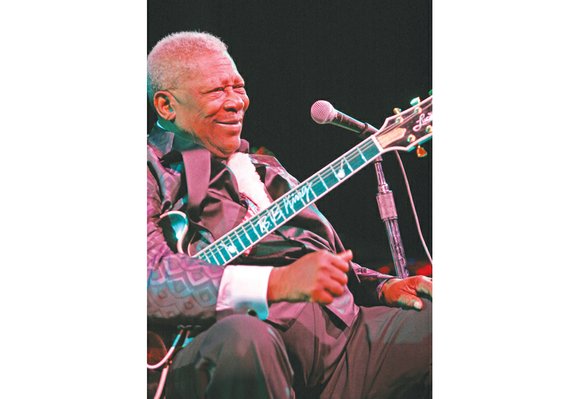

Blues legend B.B. King succumbs at 89

RFP wire reports | 5/22/2015, 11:58 a.m. | Updated on 5/22/2015, 12:04 p.m.

B.B. King believed that anyone could play the blues, and that “as long as people have problems, the blues can never die.”

But no one could play the blues like this guitar master, who died Thursday, May 14, 2015, in this Nevada tourism and gambling center where he had long made his home and where he had been in hospice care.

The music legend was 89.

Mr. King was still performing 100 dates a year well into his 80s, even though he suffered from diabetes and other health problems.

His death was attributed to a series of small strokes that was linked to his longstanding battle with Type 2 diabetes, his physician and the coroner in Las Vegas reported.

“The blues has lost its king, and America has lost a legend,” President Obama stated in a tribute.

“No one inspired more up-and-coming artists. No one did more to spread the gospel of the blues,” the president stated.

He recalled Mr. King’s concert at the White House in 2012 where the artist unexpectedly talked the president into singing a few lines of “Sweet Home Chicago” with him. “That was the kind of effect his music had, and still does. He gets stuck in your head, he gets you moving, he gets you doing the things you probably shouldn’t do — but will always be glad you did. B.B. may be gone, but that thrill will be with us forever.”

The blues genius was born Riley B. King on Sept. 16, 1925, to sharecropper parents. The initials he used were a shortened version of the “Blues Boy” nickname he was dubbed for his live performances on a Memphis, Tenn., radio station.

Along with his music, he was married twice and had 15 biological and adopted children.

His place in the pantheon of American music is well established.

Mr. King was named the third greatest guitarist of all time by Rolling Stone magazine, after Jimi Hendrix and Duane Allman, who died in their 20s, an age when Mr. King was just getting started.

A 1992 New York Times review helps explain his appeal: “Mr. King’s electric guitar can sing simply, embroider and drag out unresolved harmonic tensions to delicious extremes. It shrinks and swells with the precision of the human voice.”

He won 15 Grammy Awards, sold more than 40 million records worldwide, a remarkable number for the blues, and was inducted into the blues and rock and roll halls of fame.

His album “Live at the Regal” has been declared a historic sound and permanently preserved in the Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry.

Mr. King played a Gibson guitar he affectionately called Lucille, with a style that included beautifully crafted single-string runs punctuated by loud chords, subtle vibratos and bent notes, building on the standard 12-bar blues and improvising like a jazz master.

The result could hypnotize an audience, no more so than when Mr. King used it to full effect on his signature song, “The Thrill is Gone.”

Despite the celebrity he achieved, his farewell will be surprisingly low key.

Fans will be able to say farewell to Mr. King at a public viewing scheduled 3 to 7 p.m. Friday, May 22, at the Palm Mortuary West in Las Vegas. But there will be no memorial service.

His funeral on Saturday, May 23, will be private for family and close friends, according to LaVerne Toney, Mr. King’s business manager for 39 years.

Mr. King is to be buried next week on the grounds of the B.B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center in his hometown of Indianola, Miss., according to Allen Hammons, a member of the museum’s board of directors.

Mr. King was born in rural Itta Bena in the Mississippi Delta. His parents separated when he was 4, and his mother took him to the even smaller town of Kilmichael to live with his grandmother. His mother died when he was 9, and when his grandmother died as well, he lived alone in her primitive cabin, raising cotton to work off debts.

“I was a regular hand when I was 7. I picked cotton. I drove tractors. Children grew up not thinking that this is what they must do. We thought this was the thing to do to help your family,” Mr. King said.

His father eventually found him and took him back to Indianola. When the weather was bad and Mr. King couldn’t work the fields, he walked 10 miles to a one-room school. He quit in the 10th grade.

A preacher uncle taught him the guitar, but Mr. King didn’t play and sing the blues in earnest until he was away from his religious household in basic training with the Army during World War II.

He listened to and was influenced by both blues and jazz players, including such greats as T. Bone Walker, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lonnie Johnson, Django Reinhardt and Charlie Christian.

His first break came with gospel — singing lead and playing guitar with the Famous St. John’s Gospel Singers on Sunday afternoons from the studio of WGRM radio in Greenwood, Miss.

But he soon left for Memphis, Tenn., where his career took off after Sonny Boy Williamson let him play a song on WKEM.

By 1948, Mr. King had earned a daily spot on WDIA, the first radio station in America programmed entirely by African-Americans for African-Americans. He was initially known as “the Pepticon Boy,” pitching the health tonic between his live blues songs.

Seeking to improve on that, the station manager dubbed him the “Beale Street Blues Boy,” because he had played for tips in a Beale Street park. Soon, it became just “Blues Boy” and then just B.B.

Initial success came with his third recording, of “Three O’Clock Blues” in 1950. He hit the road, and rarely paused thereafter.

Among his Grammys: Best traditional blues album: “A Christmas Celebration of Hope,” and best pop instrumental performance for “Auld Lang Syne” in 2003; best male rhythm and blues performance in 1971 for his “The Thrill Is Gone;” best ethnic or traditional recording in 1982 for the album “There Must Be a Better World Somewhere.”

His collaboration with Eric Clapton, “Riding with the King,” won a Grammy in 2001 for best traditional blues recording.

In the early 1980s, Mr. King donated about 8,000 recordings — mostly 33, 45 and 78 rpm records, but also some Edison wax cylinders — to the University of Mississippi, launching a blues archive that researchers still use today.

He also supported his namesake blues museum in Indianola, a $10 million, 18,000-square-foot structure, built around the cotton gin where Mr. King once worked.

“I want to be able to share with the world the blues as I know it — that kind of music — and talk about the Delta and Mississippi as a whole,” he said at the center’s groundbreaking in 2005.

The museum not only holds his personal papers, but hosts music camps and community events focused on health challenges including diabetes. At his urging, Mississippi teenagers work as docents, not only at the center but also at the Holocaust Museum in Washington.

“He’s the only man I know, of his talent level, whose talent is exceeded by his humility,” said Mr. Hammons of the museum’s board.

In a June 2006 interview, Mr. King said there are plenty of great musicians now performing who will keep the blues alive.

“I could name so many that I think that you won’t miss me at all when I’m not around. You’ll maybe miss seeing my face, but the music will go on,” he said.