Virginia is for ‘Loving’

11/4/2016, 6:27 p.m.

By Lauren Northington

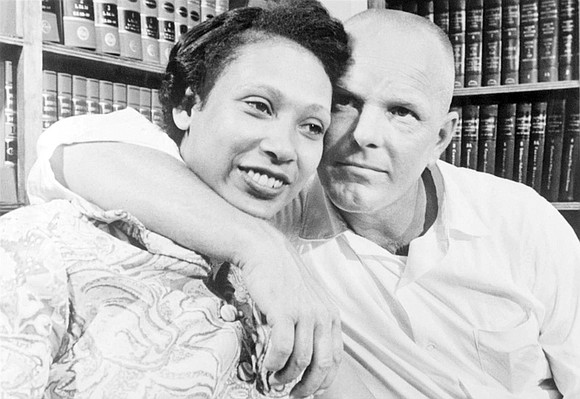

Six years after Mildred Loving’s death in Caroline County outside of Richmond, people from all over the world still post messages on a website with her online obituary.

Mrs. Loving and her husband, Richard, helped change Virginia’s and the nation’s marriage equality laws in 1967.

Richard, who was white, and Mildred, who was black and Native American, broke the law by marrying in 1958. They were arrested in their small, Central Point home for violating Virginia’s ban against interracial marriage.

Their case, Loving v. Virginia, went all the way to the U. S. Supreme Court, which overturned miscegenation laws in Virginia and 15 other states in its 1967 ruling.

The decision allowed the Lovings to return from exile to their modest Virginia homestead.

Their marriage and historic legal victory are the subject of the Universal Studios film “Loving,” which opens in theaters this Friday, Nov. 4.

The film, starring Australian actor Joel Edgerton as Mr. Loving and Ethiopian-Irish actress Ruth Negga as Mrs. Loving, was filmed last year largely in Richmond and Caroline County.

So far, the movie has received Oscar-worthy reviews.

The Lovings’ story of love without bounds continues to resonate with people everywhere. Under Mrs. Loving’s May 2008 obituary on Legacy.com, notes of admiration and thanks have been left through the years and as recently as last week. Many are from people who said her courage opened the doors for them to marry someone from another race.

Some people even posted photos of themselves with their spouse.

“Thank you for showing what our country can be at its best,” wrote Fred from Pittsboro, N.C., last week.

“Thank you for standing up for your given rights, the two of you were just amazing people: Mr. & Mrs. Loving,” stated Anne M. Gray from Los Angeles.

The Lovings married in June 1958 in the District of Columbia to evade Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which prevented marriages between white people and non-whites. The couple returned to Caroline County to establish their home.

Mr. Loving, 24, worked as a bricklayer and Mrs. Loving, 18 and pregnant, was a homemaker.

They enjoyed their life in Virginia and being surrounded by family and friends, their daughter, Peggy Loving Fortune, told the Associated Press in 2008 at her mother’s death.

But shortly after their marriage, local police busted into the couple’s home one night and arrested them. They were sentenced to one year in jail, which was suspended for 25 years on the condition they leave Virginia and not return together. The couple moved to Washington to avoid jail but experienced severe social isolation and financial difficulties, according to court documents.

After a car struck their son, Donald, in their Washington neighborhood, the homesick Mrs. Loving wrote to then-U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, who advised her to go to the ACLU.

“My husband is white and I am part negro and part Indian,” the 22-year-old Mrs. Loving wrote humbly. “We know we can’t live (in Virginia) but we would like to go back once in a while to visit our family and friends.”

Lawyers for the ACLU argued their case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The court ruled that preventing the Lovings from marrying was in violation of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which was enacted to “eliminate all official state sources of invidious racial discrimination in the states,” according to the majority opinion.

“The freedom to marry has long been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by freemen,” wrote Chief Justice Earl Warren in 1967.

Even when the ruling came down, various opinion surveys showed that interracial marriage was still intolerable among large segments of the population.

But history has shown that justice does not always align with popular opinion. Replace “racial discrimination” with “sexual orientation” and several of the arguments in recent years in support of same-sex marriage are strikingly similar to arguments used in defense of interracial marriage.

The high court even cited the Loving case in its landmark 2015 decision saying the fundamental right to marry is guaranteed to same-sex couples under the Constitution’s 14th Amendment.

Mrs. Loving, a devout Christian, stopped giving interviews for decades, but released a short statement to the gay rights group Faith in America on the 40th anniversary of the Loving v. Virginia ruling in 2007.

Asked by a Faith in America advocate if she supported the idea of marriage equality among same-sex couples, Mrs. Loving replied, “I understand it, and I believe it.”

Regardless of their barrier-breaking love, the Lovings were known as an uncomplicated couple.

Mr. Loving, before being killed by a drunk driver in 1975, also rarely spoke to reporters and continued bricklaying up until his death.

When asked by his lawyer Bernard Cohen of Northern Virginia to provide a statement to the court before the 1967 arguments began, Mr. Loving matter-of-factly replied, “Mr. Cohen, tell the court I love my wife, and it’s just unfair that I can’t live with her in Virginia.”