Felons fired up, ready to vote

10/22/2016, 1:46 p.m.

By Lauren Northington

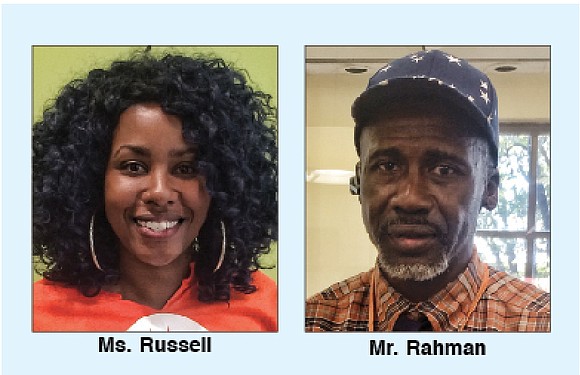

Rochelle Russell, 33, is one of 206,000 Virginians who has a felony conviction, served her time and is now living back in the community.

Now for the first time since her 2010 conviction, Ms. Russell will be able to vote in November.

“I pay taxes, I’ve paid my fines, and I’ve done my time. And I feel as though I should have a voice in the community,” Ms. Russell said Monday at a voting rights restoration roundtable hosted by the grassroots organization New Virginia Majority.

Voting is important to Ms. Russell. She said while lawmakers are “making decisions in my life, I should have a voice in that as well.”

Next month, thousands of felons in Virginia will have an opportunity to vote because Gov. Terry McAuliffe restored their voting rights despite an uproar and court battle over his executive authority to do so.

Ms. Russell is among several ex-convicts who have joined New Virginia Majority to register new voters and to organize voters around ending “disenfranchisement in general,” which she said she didn’t fully understand until recently.

“I didn’t grow up in a space where voting and civic engagement were talked about,” said the Richmond native and graduate of Varina High School in Henrico County. “Now I’ve had to make up for lost time. I wish I could go back and vote when I had the chance.”

She voted for the first time at age 26 in the 2008 presidential election.

Now Ms. Russell has taken significant time to research national, state and local candidates, a practice other felons echoed.

“Walking out of the gates of the penitentiary should be the end of servitude and submission to the will of the Commonwealth,” said Tammie Hagen, 52, who will be voting for the first time ever in November.

“The word penitentiary,” she continued, “means a place where people go to be forgiven. But preventing felons from voting, or serving as notary publics or running for public office means that our service to the state is never really over.”

Like Ms. Russell, Ms. Hagen’s rights were restored in August. Since then she has worked diligently with New Virginia Majority to register felons and first-time voters in Richmond.

Virginia’s felon disenfranchisement policy, according to Gov. McAuliffe and the Secretary of the Commonwealth’s Office, is rooted in a tragic history of voter suppression and marginalization of African-Americans and other minorities. State law bars felons for life from voting, running for public office, serving on a jury or acting as a notary public, unless the governor restores their rights.

Today, roughly 60 percent of Virginia’s prison population is African-American and 93 percent is male, according to the state Department of Corrections.

Muhammad As-Saddique Abdul Rahman, 53, said his focus before the state’s deadline on Monday was to register people to vote.

Now, he said, his focus will be on organizing.

He hopes to energize Richmond voters to work toward undoing what he terms political and economic damage to black and poor people in particular. He said that includes reminding Richmond voters of poll taxes, the creation of chattel slavery in colonial Virginia and “black codes” — Reconstruction-era policies that wrongly imprisoned black men to provide free labor — and current disenfranchisement.

“All of the wrongs are the same in my eyes,” he said.

For Ms. Russell, Ms. Hagen and Mr. Rahman and others across the state, this election means more than just casting their ballots, but influencing the policies and a culture that has contributed to the denial of civil rights for generations.

“There are so many people I meet in Richmond who say they can’t vote and will never vote — and they mean it,” Ms. Hagen said. “Because they don’t think they’ll ever be able to live a life that is worth living, that is not necessarily lucrative, but a life that’s whole and meaningful. And that’s all.”