Losing ground

City public schools slide on accreditation; only 13 of city’s 44 schools fully accredited

9/15/2016, 11:29 p.m.

By Lauren Northington

Report cards are in for Richmond Public Schools.

And many of the city’s schools didn’t make the grade, according to the Virginia Board of Education.

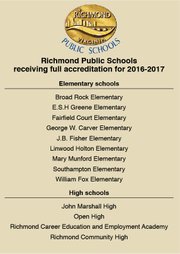

Only 13 of the city’s 44 schools received full accreditation, down four from the 17 schools that met state standards last year.

Seven schools — Elizabeth D. Redd and Swansboro elementary, Martin Luther King Jr. Middle, Armstrong High, Patrick Henry School of Science and Arts, Amelia Street Special Education Center and Richmond Alternative School — were denied accreditation.

Sixteen Richmond schools are at risk of being denied accreditation by the Board of Education. The board will determine accreditation status for those schools later this year.

The remaining eight Richmond schools received partial accreditation warnings that help the state identify how far a school is from achieving passing Standards of Learning scores and meeting graduation requirements.

“We’re nowhere near where we want and expect to be,” Jeff Bourne, chairman of the Richmond School Board, told the Free Press on Wednesday following the release of the state’s annual report on school accreditation.

“But we are in the midst of fixing and rebuilding a number of things that have been and were ignored for years.”

For a school to be fully accredited, at least 70 percent of its students must pass state Standards of Learning tests in mathematics, science and history, and 75 percent of the students must pass the English SOL tests.

In addition to the SOL pass rates, high schools also must maintain at least an 85 percent graduation rate to be fully accredited.

The ratings take into account efforts to help students who have failed the SOLs in the past.

This is the first time Redd and Swansboro elementary schools have failed accreditation. The other five are repeat offenders. This is at least the second year all five have failed.

However, accreditation ratings do account for students who retake an SOL test and pass after initially failing.

Four city schools are on warning that they would be denied accreditation next year if they fail to raise student SOL pass rates during the current academic year. They are Albert H. Hill and Elkhardt Thompson middle schools, George Wythe High and John B. Cary Elementary.

Huguenot High School received partial accreditation because its high school graduation rate is at 82 percent, which is 3 percentage points below the state standard for accreditation. It is also a drop of 5 percentage points from Huguenot’s graduation rate last year.

With seven schools denied accreditation, Richmond had 24 percent of the Virginia schools that failed accreditation. Across the state, just 29 schools in 11 of the state’s 132 school districts were denied accreditation for 2016-2017.

Overall, 81 percent of Virginia’s public schools were fully accredited. And 53 school districts had all of their schools accredited. That includes Hanover, Powhatan and Prince George counties and Colonial Heights.

In Henrico County, only one school — L. Douglas Wilder Middle — was denied accreditation. This is the third year the school has not been accredited. Forty-eight schools were fully accredited, while 18 received partial accreditation or are awaiting determinations from the state.

In Chesterfield County, no schools were denied accreditation, and five received partial accreditation or are awaiting accreditation results. Fifty-six schools were fully accredited.

Charles Pyle, spokesman for the state Board of Education, said schools that are denied accreditation must work with the state to come up with an approved corrective action plan.

“A memorandum of understanding between the Board of Education, the Richmond School Board and the superintendent is created, or amended,” he said. “This process involves providing additional tools, updating the [school] division’s academic plan and having the Richmond School Board provide a presentation to the state on plans for improvement.”

Last year’s memorandum of understanding for Martin Luther King Jr. Middle and Patrick Henry School of Science and Arts requires the schools to submit reports three times a year to the state Office of School Improvement with data on student and teacher attendance, student discipline and teacher observations.

Both memorandums of understanding would need to be amended as both schools were denied accreditation again.

Richmond schools Superintendent Dana T. Bedden said the repeated failures and warnings from the state Board of Education for certain city schools are indicative of “basic needs and social issues from the community.”

“Many of our schools were already on this trajectory, and correcting this is a process, not a single action,” Dr. Bedden said in a statement. “Addressing the years of challenges will take more than two school years. Some challenges in school performance are indicative of the challenges faced by the community at large.”

Dr. Bedden is completing his third year as Richmond’s superintendent. He started in January 2014.

He said his administration has been working to improve student access to food after school and on the weekends and on training teachers to better understand the trauma many of the city’s students cope with.

He also is implementing, in cooperation with the state Department of Education, a new approach to school improvement that he calls the School Progress Plan.

“Each school, regardless of accreditation, will have a SPP,” said Mr. Bourne. “Those plans will be developed and communicated so people can see them and hold the school system accountable,” he said.

Both Mr. Pyle and Mr. Bourne had their own solutions to improving schools.

“One key action that has to take place in developing a corrective action plan specific to the schools’ needs is a conversation with the community,” Mr. Pyle told the Free Press.

“We have to do two things,” Mr. Bourne added. “We have to first make sure we have quality teachers in each school, and secondly, our city has to make sure our school have the resources that will show significant progress for our students.”

Mr. Bourne remains hopeful about the future of education for the city’s children. The school system “can’t change what’s been done,” he said.

Instead, he said, RPS needs to “learn from it, move forward and try and make progress.”