Executive Mansion dedicates garden to memory of enslaved

9/24/2016, 2:54 p.m.

By Lauren Worthington

Imagine living and working hundreds of miles away from your family for years, with no smartphone, no internet, no means of transportation and no sense of how far you are from home.

Now imagine being unable to read or write, but figuring out a way to communicate.

This was the reality of dozens of enslaved people from Abingdon, in Southwest Virginia, who had family members who were taken to live and work in Richmond at the Governor’s Mansion.

Hannah Valentine and Lethe Jackson were house slaves on the Abingdon farm of former Virginia Gov. David Campbell.

When Gov. Campbell and his wife, Mary, moved into the Executive Mansion in 1837 with several of their slaves, Ms. Valentine and Mr. Jackson were made to stay in Abingdon to care for the homestead.

But during Gov. Campbell’s four-year term in office, Ms. Valentine and Mr. Jackson managed to send several letters from the farm to their children and other relatives enslaved in the Richmond mansion.

The letters are being memorialized in a newly redesigned Executive Mansion garden. The garden, located directly behind the old slave quarters of the mansion that was built in 1812, was dedicated Wednesday as the Valentine-Jackson Memorial Garden. The small ceremony took place amid a torrential downpour.

“It is very unusual to have documented thoughts of enslaved persons on record in our archives,” said First Lady Dorothy McAuliffe, wife of Gov. Terry McAuliffe.

“There was something very forward-thinking about the idea that these people who were also part of the story thought that there was meaning and value in being able to communicate.”

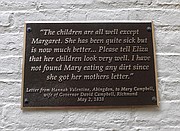

Four letters found in Duke University’s archives were filled with the longing and anxiety of separation. Excerpts of an 1838 letter from Mrs. Valentine to her husband, Michael Valentine, at the mansion, detail the health of their children and those of other enslaved persons still in Abingdon.

“Our children are very well and are free from the cough which usually succeeds the measles. Tell Eliza her children grow very fast. They do not talk much about her now, but seem to be very well satisfied without her. I begin to feel anxious to see you all. I am afraid my patience will be quite worn out if you do not come back soon,” Mrs. Valentine wrote.

Archivists now know she had not seen her husband for at least a year when the letter was written.

The Valentine-Jackson Memorial Garden, one of three on the mansion’s property in Capitol Square in Downtown, was developed in collaboration with the Urban and Regional Planning program students and faculty at Virginia Commonwealth University’s L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, the Virginia Capitol Foundation, the Capitol Square Preservation Foundation, the mansion’s Citizens’ Advisory Council and the Garden Club of Virginia.

“We have come to have a deeper understanding of the lives and suffering of these families,” said Mrs. McAuliffe.

“The letters give unique insight and show us the intimate feelings of families separated by slavery. As parents, it is extremely difficult to imagine being forcibly separated from our children. It has been a very personal and poignant coming to terms with the reality of what enslaved peoples endured.”

Charles Funk Masonry restored the mansion’s original slave kitchen, and Bunkie Trinite Trophies helped create the plaques along the garden wall that contain excerpts from the letters.

Tom Camden, an associate professor and head of Special Collections and Archives at Washington and Lee University in Lexington and member of the mansion Citizens’ Advisory Council first brought the letters to Mrs. McAuliffe’s attention in an April 2014 meeting.

According to Mr. Camden, literate slaves wrote the letters on behalf of Mrs. Valentine and Mr. Jackson. After his return to Abingdon in 1840, Gov. Campbell purchased Mary Burwell, a literate slave who taught Mrs. Valentine and Mr. Jackson how to read and write.

Copies of the original letters can be found online at the Special Collections Library at Duke University.

The mansion’s slave quarters have been used as guest bedrooms since 1999 renovations, but still feature the original kitchen used by the enslaved to prepare meals for the first family and their guests.

Mrs. McAuliffe hopes that the Valentine-Jackson Memorial Garden will not only memorialize the enslaved persons who worked in the mansion, but reignite interest in the connection of humans and nature.

“We hope to provide a place of reflection and remembrance and to give context to the heartbreak and suffering endured by individuals like Hannah and Lethe, who were separated from their family members who lived and worked at the Governor’s Mansion.”

Tours of the mansion, which will now include the Valentine-Jackson Memorial Garden, are free and open to the public. Tours are held 10 to noon and 2 to 4 p.m. Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday and last approximately 30 minutes.

For details, or to make optional reservations for a mansion tour, go to https://executivemansion.virginia.gov/tours.