Nat Turner links black, white George Wythe High alumni

3/4/2017, 11:44 a.m.

By Leah Hobbs

Nat Turner, who led one of the bloodiest rebellions of enslaved people in history, has connected the members of the George Wythe High School Class of 1974 in a unique way.

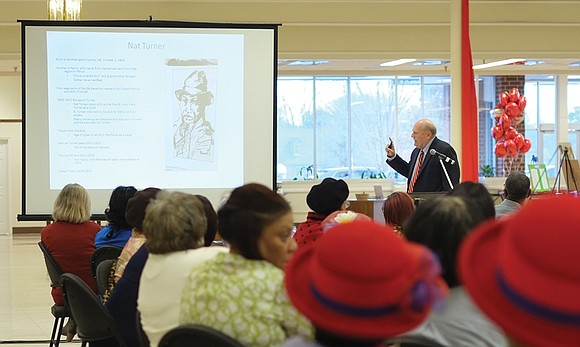

At a Black History Month Breakfast Program on Saturday at Second Baptist Church in South Side, the George Wythe class presented two speakers who personify the entwined history of African-Americans and white people in Virginia.

In this case, it was a descendant of Mr. Turner, a slave in Southampton County, and a descendant of white slave owners in the county who wound up generations later with Mr. Turner’s Bible.

The Rev. Torlecia Bates, a Turner descendant was raised in Southampton County. Her father, Torris Brooks, who didn’t attend the event, is a member of the Class of 1974 of Richmond’s George Wythe High School.

Mark Person, whose relatives donated Mr. Turner’s Bible to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2010, also graduated in the George Wythe Class of 1974.

They shared their thoughts and stories with an audience of about 100 people at the breakfast program.

When a Southampton County church refused to baptize Mr. Turner, the Person family allowed Mr. Turner to be baptized at Person’s Mill Pond, located on the family’s church property, Mr. Person recounted.

In 1831, Mr. Turner led a rebellion in which about 55 white people were killed over three days. Among the dead were some of Mr. Person’s ancestors, but his great-great grandmother, 19-year-old Lavinia Francis who was pregnant at the time, was saved by Red Nelson and other slaves who hid her.

“If it weren’t for the slaves, we would not be here today,” Mr. Person said.

Long before the rebellion, Mr. Turner, who was able to read and write, was given a Bible. It became a significant possession of his as he became a preacher. Passages also served as his inspiration for the rebellion, according to historical accounts.

Once the rebellion was suppressed, Mr. Turner hid for two months. He was found with his Bible and a sword, Mr. Person said.

After his trial and subsequent hanging, the Bible was kept in the Southampton County courthouse until the court turned it over to the Person family in 1912. The family kept the Bible in their home, Mr. Person said, and passed it down through the generations.

With the opening of the new museum in Washington, the Person family decided to donate it to the museum. The family, he said, believed that such a significant piece of history needed to be preserved and displayed for the public and the Smithsonian was the best place for it.

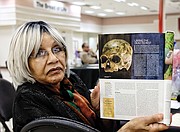

Evelyn Hawkins, a retired librarian from John Marshall High School who has ties to another significant relic possibly connected to Nat Turner, also spoke.

Last fall, Mrs. Hawkins' relatives were given a skull believed to be that of Mr. Turner, who was captured on a Southampton County farm her family now owns. Her great-great-grandmothers were born as slaves on the farm. Her grandfather, she said, later purchased the farm from the Musgrave family. It has now been in her family for 101 years.

Since growing up on the farm, Mrs. Hawkins recalls hearing stories about Mr. Turner, whose life and rebellion were the subject of the film, “The Birth of a Nation,” last year by director and actor Nate Parker.

“The rebellion was bloodier than what could ever be put on a screen,” Mrs. Hawkins said.

People are interested in seeing the spots in Southampton where events unfolded, she said. An iron stake marks the spot on her family’s farm where he was captured; a park is being planned, she said.

According to historical accounts, Mr. Turner’s body was mutilated after he was hanged.

The skull currently is being analyzed by experts at the Smithsonian, Mrs. Hawkins told the gathering. DNA testing is being conducted to see if it is possibly that of Mr. Turner.

“If it is Rev. Turner, we want to give him a decent burial in Southampton,” Mrs. Hawkins said. “If it is not him, we still want to bury the skull because every human being deserves that dignity.”

Rev. Bates talked about Rahab, a prostitute in the Bible’s Book of Joshua, who was able to make a difference despite rejection because of her past.

Similarly, she said, African-Americans have been labeled negatively by society, often simply because of the color of their skin. But they, too, can make a difference.

“We have been labeled as rejects for quite too long now,” she said.

But the faith of someone rejected is all that is needed to be an agent of change, she told the group. This is the same faith that gave hope to Mr. Turner. It is the same faith that gives hope today to those who fight for black lives today, she said.