Owners seek return of Maggie Walker papers

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 3/4/2017, 9:30 a.m.

Eight years ago, curious students from the College of William & Mary stumbled across a treasure trove of documents hidden in the attic of a vacant building in Gilpin Court.

The building once housed the Independent Order of St. Luke, a mutual aid society, and the documents provide more information about the organization and its noted leader, Maggie L. Walker, the pioneering civic leader who pushed black economic empowerment before her death in 1934.

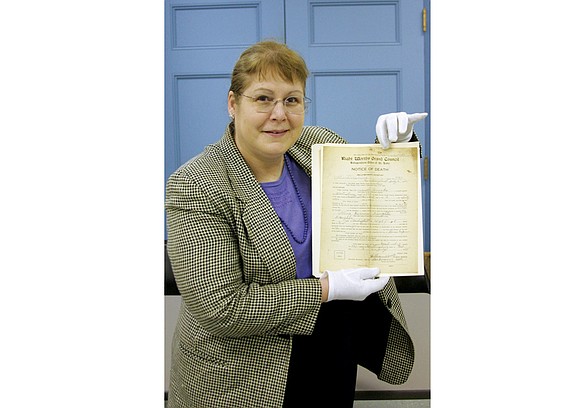

Ever since the find, Heather A. Huyck of the College of William & Mary, has led a team of volunteers in conserving and cataloguing the 15,000 documents that her students found neatly packed in more than 30 boxes.

The documents range from bills and insurance documents to Mrs. Walker’s personal correspondence with people like NAACP leader W.E.B. DuBois and Bethune-Cookman University founder Mary McLeod Bethune.

The papers are expected to add fresh insight into the Order of St. Luke’s department store, newspaper and bank that Mrs. Walker created while presiding over the organization she led from near bankruptcy to prosperity. She was the first African-American woman to charter a bank.

Next week, with the city working to complete a monument to Mrs. Walker in Downtown, Dr. Huyck will join with the National Park Service and the National Collaborative for Women’s History Sites in celebrating the completion of the preservation work.

The program will highlight the extraordinary collection and those who participated in the painstaking effort of sorting, protecting and digitizing the documents. It also will highlight the Stallings family that owns the building where the documents were found.

The invitation-only program is set for 10 a.m. Friday, March 10, at the historic Hippodrome Theater in the 500 block of North 2nd Street, according to Andrea Dekoter, chief of interpretation and education at the National Park Service’s Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site that includes Mrs. Walker’s former home in Jackson Ward.

While the NPS has hopes that the documents could end up at its site, Ms. Dekoter said “the final decision will be up to the Stallings family, which owns the documents.”

Wanda D. Stallings, a co-owner of the St. Luke Building with her mother, Margaret T. Stallings, said they have other plans.

Ms. Stallings said she appreciates the work Dr. Huyck and her team have done to protect and catalogue the documents, but she and her mother want the papers “to go to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, which currently does not have anything about Maggie Walker.”

Through her attorney, Alexander Ayers, Ms. Stallings and her mother have requested that Dr. Huyck return the papers.

Dr. Huyck is a W&M research associate and adjunct history professor. She also is past president of the women’s history collaborative.

According to Mr. Ayers, Mrs. Stallings is the rightful owner of the documents and of the four-story landmark building at 900 St. James St., where the documents were stored.

Mrs. Stallings inherited the building and other properties following the death in 2000 of her husband, James Stallings. A major landowner in Jackson Ward and Gilpin Court, Mr. Stallings purchased the building in 1971 as the Order of St. Luke was dying, with hopes of one day restoring the building to use.

Mrs. Stallings and her daughter have created a limited liability company to pursue redevelopment of the 114-year-old building and the land around it that they also co-own. Already, they have begun to fix up the exterior of the building that is boarded up and surrounded by a security fence. Workers are repairing and replacing mortar and doing other exterior restoration work.

Ms. Stallings has long been irked at the claims of Dr. Huyck that the papers had been lost until her students “discovered” them in 2009.

“That’s just false,” Ms. Stallings said.

In fact, Ms. Stallings said she and her late father lugged the boxes of papers from a safe on a lower level of the building to the attic in 1979 after a series of break-ins.

“We knew how valuable they were, and we put them in the attic for safekeeping,” she said. “We were sure no one would go in the attic. I also covered them with old newspapers and other paper to camouflage them. We always planned for them to go to an appropriate place.”

The students from Dr. Huyck’s class got involved 30 years later when they arrived from Williamsburg to shoot a documentary about Ms. Walker and the building with the support of Jackson Ward developer Ronald Stallings, a son and brother of the owners.

He also allowed the students to explore the building. When they reached the attic, they found the papers, about which Mr. Stallings was unaware. After Dr. Huyck learned about the documents, she received permission from Mr. Stallings to take them back to the college.

“At the time, I was in the hospital battling cancer,” said Ms. Stallings, who added the disease is in remission following 17 operations and other treatments. “I wasn’t upset about what he had done, though he really didn’t have authority to allow the papers to be removed, because they were supposed to eventually come back to us.”

Mr. Stallings said Tuesday that he gave permission for Dr. Huyck to take the papers, but only on the condition that they would be returned to the family once the work was done.

He wants the papers to be donated to the Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, but Ms. Stallings said her brother “does not have a say.”

Ms. Stallings said the first she heard about the Hippodrome event was when Dr. Huyck called her mother in February seeking “to get her to sign a release form to give her the papers.”

Dr. Huyck apparently was seeking the release as her plan was to donate the papers to the National Park Service, for whom she previously worked as a public historian for 30 years.

But “I told her my mother would not sign the release,” Ms. Stallings said.

Dr. Huyck did not respond to a Free Press request for comment.

Ms. Stallings said the family has received no response from Dr. Huyck to their lawyer’s Feb. 24 letter.

Still, what is clear is that the papers of Ms. Walker and the Order of St. Luke are now in better shape.

After getting the papers to the college, Dr. Huyck recruited a team of students and African-American women from the Williamsburg-James City-York County NAACP and the Williamsburg affiliate of the National Association of Negro Business and Professional Women’s Clubs to help sort, catalogue and protect them.

Trained by Dr. Huyck and other historians, the volunteer team has carefully transferred the documents into acid-free boxes, then page-by page, put them into acid-free folders, according to a description of the work, to keep them from further deterioration.

The documents have needed gentle handling; some were to the point where they were falling apart, Dr. Huyck previously reported.

Swem Library at the school also has digitized the material so it can be available to scholars and the public on the college’s website.

“The stories of Maggie Walker and others like her are lost every day,” Dr. Huyck told USA today in a 2016 interview in describing the importance of the work.

“If we don’t have the documents, the history we write is made up and not real. We need to find and preserve them before they are gone,” she said.

“That’s where the collection becomes so important,” she said in a 2013 interview for a William & Mary publication. “It tells us things not available anywhere else.”

Such documents are not easy to come by. The Order of St. Luke continued for several decades after Mrs. Walker’s death in 1934, but many of its documents were lost after it was shut down.

Even the bank she founded is no more. Later known as Consolidated Bank & Trust Co., it continued until 2011 when its charter was withdrawn during its merger with the current owner, Premier Bank of West Virginia.

Connie Cook-Hudson, one of the volunteers who took part in the preservation work, once told a reporter the documents show “how wonderful a woman she was in her time, dealing with business matters and helping her community get established.”

The papers, she said, are “like you’re reading a book about a great woman.”