When Rihanna dressed as the pope

5/21/2018, 10:36 p.m.

Timothy P. O’Malley

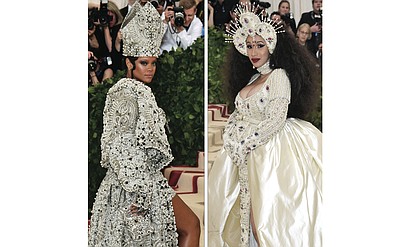

Rihanna came as a burlesque pope. Cardi B was a vaguely medieval madonna. Madonna, meanwhile, as a queen draped in black, was strikingly sedate. At the Met Gala on May 7, Catholicism was beyond chic.

The Met Gala — the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s annual fundraiser to benefit its Costume Institute — has become the New York fashion world’s high holiday, a contest of sorts in which movie stars, music idols, professional athletes and all manner of undefined celebrities try to outdo one another for the most over-the-top or dazzlingly elegant formal wear.

This year, the ball’s theme was “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination.” For practicing Roman Catholics, watching the red carpet coverage was at once thrilling and troubling.

On the one hand, a proud Catholic could see the festivities and the accompanying exhibit, which had the cooperation of the Vatican’s Department of Culture, as a welcome way for the church to engage with one of the most intensively followed and creative sectors of popular culture.

This would hardly be a breakthrough. As the haute couture worn at the event seemed to recognize, Catholicism has a deep design history that is all but inseparable from Western material culture. It’s easily forgotten today that Catholicism once reached into every sphere of life, including fashion, architecture and music. For one sequin-studded night (and for the duration of the exhibit), the general public had occasion to ponder the church’s long cultural treasury. It may even have led some to wonder, “Perhaps, there’s something for me in the church.”

The eruption of enthusiasm on Twitter and Instagram the night of the gala testifies to this possibility. It’s hard to imagine that those commenters, even those more interested in Versace than the Vatican, could fail to ponder the meaning of the processional crosses, reliquaries and vestments on display. Those who attend the exhibit may find their way down Fifth Avenue to the door of St. Patrick’s Cathedral some Sunday to see if this liturgical finery is still in use. (Spoiler alert: It’s no small part of what brings us Catholics back each week.)

Another view would caution, however, that the Met Gala linked the church to a cult radically different from the one honored in the daily Mass — the cult of celebrity.

Yes, for a hot second, everyone was focused on the church’s sartorial and perhaps even its spiritual legacy. But they were more likely thrilling to the sight of Rihanna strutting under a papal-white miter.

For those disposed to object to the Met’s Catholic moment, the primary critique is sacrilege. The gala and exhibit align the church’s treasury of beauty too closely with a trend-obsessed culture. For Catholics, images of the Blessed Virgin Mary are not merely objets d’art, and the sight of rosary beads adorning a bondage mask has a spiritual cost.

In reality, there is truth in both takeaways. No, this was not the most sacrilegious event in the church — there is a long history of carnival in the church. In the Middle Ages, a boy dressed up as bishop would lead the crowds in nonsense prayers on the feast of St. Nicholas. Such playful role reversals, besides being entertaining, were a healthy reminder that the church’s authority and power comes not from human leaders but from Christ alone.

Not long ago, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI offered a better definition of sacrilege than playing dress-up. On a trip to Portugal in 2010, he stated that the greatest danger to the church was not outside enemies but the sin of her members. Every time a Catholic receives the Eucharist and then enacts violence against God or neighbor, sacrilege unfolds.

At the same time, the church needs to take care not to affiliate too closely with celebrity in a world where what people crave most is an authentic encounter with other people. Celebrities cavorting in inordinately expensive gowns that riff on ecclesiastical dress has nothing to do with the margins, where Pope Francis has called disciples to go. As immigrants fearing deportation look to the church for help, we can’t be distracted by who wore it better — the pope or Rihanna.

My undergraduates, especially those suspicious of ecclesial power and authority, are not the kind of people who find such cultural excess attractive. They want an authentic encounter with truth, goodness and beauty.

Cultivating an interest in the Catholic imagination among an elite group of human beings residing in one of the most expensive cities in the world may well cause some to remember their faith or seek out the church for the first time. Then, the real work begins for those of us they find there — to show why these images are a source of meaning, a source of beauty, a source of love.

Without this work, the church’s experiment with evangelization through high fashion may be chic. But it also will be forgotten.

The writer is director of education for the McGrath Institute for Church Life and a professor in the department of theology at the University of Notre Dame.