Maternal mortality: Black women far more likely to die giving birth than Caucasians

By Arianna Coghill and Kaytlin Nickens/Capital News Service | 5/10/2019, 6 a.m.

Last fall, Tanca McCargo, a Chesterfield native, found out she was expecting her second child. Ms. McCargo, who already had a 3-year-old son, discovered early on that her second pregnancy would be different. Her complications began when she experienced light bleeding.

“The morning after scheduling an appointment with my OB-GYN, I passed an actual blood clot,” Ms. McCargo said.

She was sent to the emergency room for a transvaginal ultrasound, which allowed doctors to examine her reproductive organs. They found that Ms. McCargo’s pregnancy was ectopic: Her fertilized egg had attached to her fallopian tube instead of to her uterus.

Ms. McCargo, 22, faced a life-and-death dilemma. If she proceeded with the pregnancy, her fallopian tube likely would rupture, causing internal bleeding and possibly her death.

There was only one other option. “I couldn’t keep the baby,” Ms. McCargo said. “That was the most heart-wrenching and traumatic experience I’ve ever had in my life.”

Three months into the pregnancy, Ms. McCargo decided to have an abortion. But it did not go smoothly. Doctors gave her chemotherapy injections to stop the fetus from growing, but the injections initially didn’t work.

“Those injections made me feel horrible. I was nauseated almost all day every day,” Ms. McCargo said. “I experienced extreme fatigue. I slept less. It was just overall mentally and physically exhausting.”

Eventually, the abortion was performed. Ms. McCargo is still recovering from her ordeal. Currently, she is a stay-at-home mom caring for her son, Zakhai.

Her situation is not uncommon. For black women, childbirth can be a death sentence.

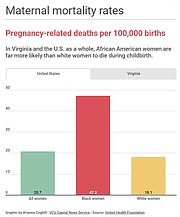

Nationwide, African-American women are three to four times more likely than white women to die from pregnancy-related causes, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That is true in Virginia as well.

Among white women in the commonwealth, there were 11 maternal deaths per 100,000 births last year, the nonprofit United Health Foundation reported. But among the state’s African-American women, there were 36.6 maternal deaths per 100,000 births.

Virginia’s chief medical examiner highlighted the racial disparity in a report released last month.

“Black women in the United States and Virginia are known to suffer the greatest burden of pregnancy-associated death, a perplexing and consistently reported fact. In each of the 15 years of pregnancy-associated deaths reported in Virginia, the mortality ratio for black women exceeded that for white women,” the report stated.

On the national stage, several African-American women have stepped forward with their own experiences of pregnancy-related challenges.

In an HBO series, tennis star Serena Williams, who gave birth to her daughter, Alexis, in 2017, described having complications during her pregnancy and labor. And in a Netflix special, Beyoncé opened up about the difficulties she faced when pregnant with twins two years ago. She experienced preeclampsia, a sudden, potentially life-threatening increase in blood pressure.

Are black women treated differently?

Throughout her pregnancy, Jazmine Brown felt uneasy, filled with unexplainable emotions and pressure. She especially resented visiting her doctor.

Ms. Brown said the doctor treated her dismissively — not like the other patients. She said she wasn’t sure whether the reason was because she was “young and black” or her insurance situation.

“I felt like they didn’t want me to be there — like I was inconveniencing them,” said Ms. Brown, who worked and attended Tidewater Community College at the time.

“When I was pregnant, I had Medicaid to pick up what my job insurance wouldn’t,” she said.

Ms. Brown said that she received a lot of backlash at her prenatal visits and that the pressure began to weigh on her. The situation came to a head when “we had an ultrasound appointment and I was no more than 5 minutes late.”

Ms. Brown said she arrived at the building on time, but was late to the doctor’s office because she had to take the stairs.

“I was only 23 at the time, and she felt like it was OK to yell at us for being late. I had never been late before,” Ms. Brown said.

“I will not settle for that treatment again,” she said. “I know they saw me just as a ‘poor little black girl.’ ”

Ms. Brown subsequently gave birth to a daughter, Jamie. Now 24 and living in the Virginia Beach area, Ms. Brown is a student at Norfolk State University.

Research suggests that it wasn’t Ms. Brown’s imagination that she felt mistreated and agitated during her pregnancy. African-Americans sometimes are treated differently by health care providers and experience greater pregnancy-related stress, studies show.

According to a 2016 study by the University of Virginia, black people are systemically undertreated for pain in relation to white people. Researchers found that a substantial number of white medical professionals and students held false beliefs about biological differences between black and white people.

Moreover, the nonprofit Seleni Institute found that black and Latina women are at a higher risk for mental health issues after pregnancy. Backing that up, the Icahn School of Medicine found that 44 percent percent of black women — versus 31 percent of white women — reported symptoms of depression after their pregnancy.

Maternal mortality rates have alarmed members of the Virginia General Assembly.

At the start of the 2019 legislative session, Democratic Delegates Lashrecse Aird of Petersburg and Marcia Price of Newport News introduced a resolution “recognizing the maternal and infant mortality crisis in the United States.”

The resolution stated in part:

• The United States is the only industrialized country with a rising maternal mortality rate.

• Maternal and infant mortality “is exacerbated by factors such as poverty, gender inequality, age, and multiple forms of discrimination, as well as factors such as lack of access to adequate health facilities and technology and lack of infrastructure.”

• “Considerable racial disparities in pregnancy-related mortality exist, with deaths per live birth for black women nearly three times higher than such deaths for white women.”

• “The root cause of these disparities is longstanding structural racism, which has contributed to poorer health outcomes among communities of color.”

The House Rules Committee never held a hearing or voted on the resolution. However, the General Assembly passed a bill requiring the Virginia Department of Health to review the rate of pregnancy-related deaths.

Under HB 2546, the department will establish the Maternal Death Review Team, which will include state health officials and outside experts.

The bill was sponsored by Republican Delegate Roxann Robinson of Chesterfield and Democratic Delegate Kaye Kory of Fairfax. It says the team will improve data collection and record keeping regarding maternal deaths and recommend ways “to increase awareness and prevention of and education about maternal deaths.”

On April 3, the General Assembly unanimously approved minor changes that Gov. Ralph S. Northam had recommended concerning HB 2546. It will take effect July 1.