Food fight

Highland Springs-based food ministry scrambles to generate new food sources after being shut out by Feed More

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 10/4/2019, 6 a.m.

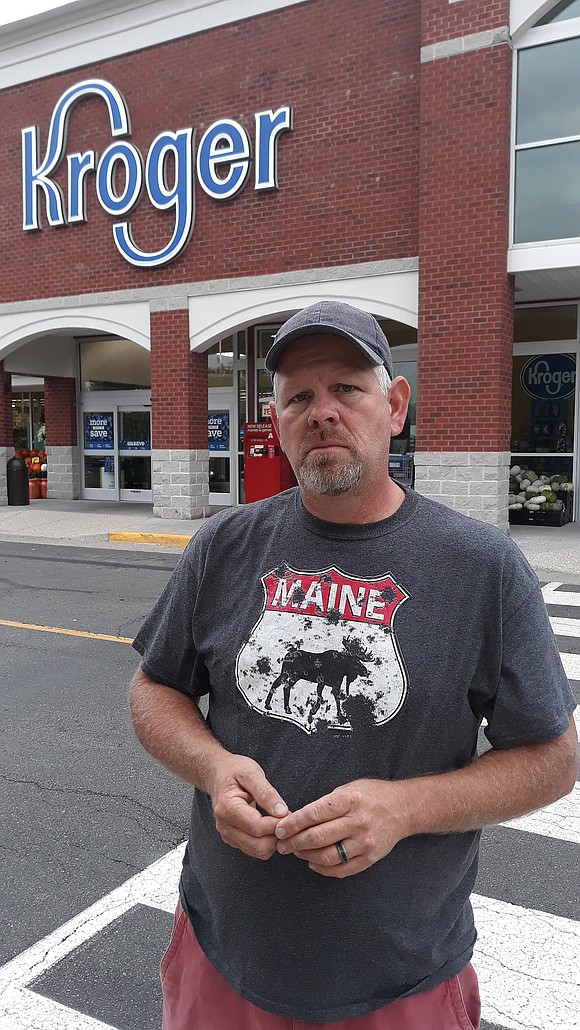

For the past year, Brian Purcell has stopped by the Kroger store in Mechanicsville four days a week to pick up unsold prepared food and bakery items the store otherwise would have thrown away.

“It’s been a godsend to the seniors and homeless veterans we serve,” particularly people with diet restrictions, said the 48-year-old founder of The Way, a Christian food ministry currently based in Highland Springs that he started four years ago.

While the Kroger store is not his only source of donated food — his ministry also picks up unsold sandwiches from Wawa, Sheetz, Starbucks and similar retail outlets — he said the Kroger items helped him, his small staff of five and a cadre of 25 volunteers to serve 3,000 people a month in Hanover, Henrico and Richmond.

Many of those served, Mr. Purcell said, have little income. Without The Way, most would have to choose between buying food and paying the rent or purchasing medicine, he said.

But the donated Kroger food is no longer available to The Way. An unlikely adversary, Richmond-based Feed More, has cut off Mr. Purcell’s access.

Feed More is the Richmond-based hunger-relief giant that provides nearly 21 million meals annually to 200,000 people in need in 34 counties and cities in Central Virginia.

Tracing its roots back 52 years, the nonprofit generates $60 million a year in revenue — nearly 1,000 times as much as The Way’s shoestring annual budget of $66,000. Feed More, which has more than 1,600 volunteers and more than 100 paid staff, operates, among other programs, the Central Virginia Food Bank to collect and distribute donated food, runs the area’s Meals on Wheels program and prepares food in its kitchen for distribution to children in after- school programs.

According to Douglas Pick, president and chief executive officer of Feed More, the food that Mr. Purcell collected from Kroger for his ministry already was promised to other food distribution groups that are partner agencies with Feed More, unlike The Way, which is not.

Like other food banks across the country, Feed More is an affiliate of the national Feeding America organization, which has worked with national grocery chains to resolve the issue of what to do with their unsold food.

Under agreements forged since 2010, Feeding America has created contracts with the chains to steer their still unspoiled discards to the food banks and their partners.

To secure that food and get it to people in need, Mr. Pick said Feed More’s practice is to have its 280 partner agencies in Central Virginia go to chain grocery stores to collect the unsold food, from meat and produce to baked goods. Each group is assigned a specific supermarket, Mr. Pick said. Several agencies can be assigned to a supermarket, with each having a designated day or designated days to collect to ensure daily pickups, he said.

Feed More reports that grocery retailers provide more than 60 percent of the donated food that the organization distributes, with unsold food representing a significant share of the total. So despite his wish to accommodate Mr. Purcell, Mr. Pick said The Way is a disruption to that system.

Mr. Pick said the issue could not be ignored when “a Feed More agency, which participates in our Direct Store Pickup Program, stated that they had not been getting their designated bakery and deli food pickups on their designated pickup days from the store.”

He continued, “Currently, we have three agencies that pick up perishable donations from the meat, produce, deli, dairy and bakery departments from (the Mechanicsville) store seven days a week.”

Mr. Purcell said that was news to him, based on his observation and what he was told by store employees, who previously never saw representatives of any other agency come to pick up deli items and bakery goods on the Tuesdays, Thursdays, Saturdays and Sundays when Mr. Purcell made collections.

Feed More and Mr. Purcell tried to negotiate a settlement during the summer, under which Mr. Purcell would become a partner agency.

But Mr. Purcell said he dropped that idea when Feed More told him that the Kroger store’s food was spoken for and he would have to go on a waiting list.

“That wouldn’t do,” he said.

Once the talks ended, Feed More, which by contract has first dibs on any food Kroger is discarding, notified the company and the store that further distribution to The Way would violate the agreement with Feeding America.

Mr. Purcell, who was cut off Sept. 4, has watched the food supplies in The Way’s freezers and refrigerators fall sharply since then. He is scrambling to make up the loss of food from Kroger so he can continue to serve The Way’s clients.

“We have 13 senior communities that we deliver to regularly,” he said, with at least 175 people getting meals twice a month. And that doesn’t count The Way’s deliveries to others or donations to the walk-ins who pick up at the group’s headquarters at 1138 W. Nine Mile Road. “All of the people we serve are being affected by the food shortage we are experiencing,” he said.

He is searching for other grocery stores willing to donate, though he acknowledges that the Feed More monopoly on chain supermarket donations is likely to make that difficult.

Meanwhile, he and his staff are doing more work to prepare food for the people The Way serves. He said they are repackaging sandwiches they receive from Wawa and other locations to meet specific dietary restrictions.

Mr. Purcell also is seeking to boost The Way’s revenues to enable The Way to buy replacement food that it would prepare. He is opening a thrift store operation at the Nine Mile Road location, offering yard care and considering other revenue-producing business possibilities while also trying to boost monetary donations.

He admits it is tough. Given the current $66,000 budget, The Way really can’t afford to buy a lot of food, he said. Like Feed More’s Meals on Wheels, The Way charges a delivery fee to seniors with diet restrictions to cover insurance, gas and other costs, but the people the ministry serves cannot afford a significant increase.

“We have faced challenges before,” Mr. Purcell said. “I can’t let this setback keep me and The Way from continuing this mission. Too many people are depending on us.”