MLB icon Lee Smith almost had basketball career

Fred Jeter | 1/29/2016, 7:22 a.m.

Before Lee Arthur Smith became one of baseball’s ace relief pitchers, he was affectionately known as “that other guy” back home in tiny Castor, La.

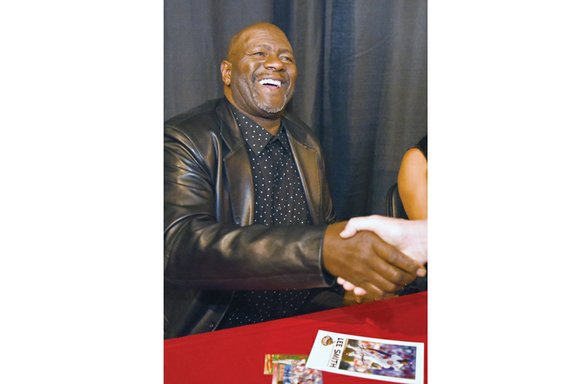

Smith, a guest at the Richmond Flying Squirrels’ annual Hot Stove Banquet last Thursday at the Siegel Center, spoke of the day his sporting focus shifted from basketball to baseball.

“I was pitching against a hot local prospect — actually the nephew of Vida Blue,” Smith recalled.

Blue played in the major leagues from 1969 to 1986.

Now 58 and a Major League Baseball icon, Smith’s dark eyes sparkled while relating the story from decades ago.

“A bunch of scouts were there to see Vida’s nephew. Then one of the scouts shouted to another, ‘Who’s that other guy?’ ”

The scout was asking about Smith, the opposing pitcher.

“That got in the newspaper the next day,” Smith said of the Mansfield Enterprise. “I’ve still got a copy,” Smith said. “People started calling me ‘that other guy.’ ”

Word spread about the hard-chucking, 6-foot-6 right-hander, and in 1975, Smith became the Chicago Cubs’ second-round draft pick.

He chose baseball over basketball for one reason:

“Money,” he explained jovially.

“Baseball paid up front with a signing bonus. College basketball just involved a scholarship.”

So at 18, with a few bucks in his pocket, Smith began a storied journey in which he achieved pitching greatness — but not without a few zigs and zags along the route.

In fact, in 1978 while working on the Cubs’ farm club in Midland, Texas, Smith took “early retirement,” returned home and joined the basketball team at Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, La.

Chicago All-Star Billy Williams, an African-American who had befriended Smith during the Cubs’ spring training, talked him out of the dubious career change.

By the early 1980s, Smith had become the unquestioned star of the Cubs’ bullpen. Often he was called on to save games of legendary African-American hurler Ferguson Jenkins (284 career wins), a Chicago teammate of Smith’s in 1982 and 1983.

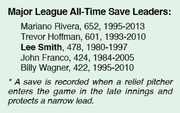

Smith retired as baseball’s all-time leader in saves with 478. Since then, his record has been surpassed by Mariano Rivera and Trevor Hoffman.

In all, the seven-time All-Star pitched in 1,022 games, striking out 1,251 batters in 1,290 innings, while compiling a 3.03 earned run average.

Unlike most “closers” today, who pitch only the ninth inning, Smith often worked multiple frames for his saves.

Much has changed in terms of baseball demographics since Smith was in his fire-balling prime.

In 1981, Smith’s second season, African-Americans made up an all-time high 18.7 percent of big leaguers. This past season, the number had dwindled to just 7.8 percent.

More often that not, talented young black athletes are choosing basketball and football over baseball.

“There are a lot of reasons,” said Smith.

“Partly, it’s the travel. A family can spend thousands nowadays going here and there. It wasn’t like that when I came around.”

But expenses aren’t the only hurdle.

“I just don’t think young black kids find (baseball) exciting anymore. I have two sons, ages 27 and 22, and I couldn’t get them to play,” he noted, wincing at the memory.

“They told me it wasn’t exciting enough.”

Smith’s top season was in 1991 with St. Louis, when he saved 47 games, finishing second to Atlanta’s Tom Glavine for the National League Cy Young Award and eighth for Most Valuable Player.

Just goes to show that baseball scouts need to avoid tunnel vision and keep an open eye for talent. You never know when “that other guy” might turn out to be the best of all.