New ‘Roots’ relevant to new generation

6/3/2016, 12:12 p.m.

By Jack White

Special to the Free Press

In the history of American television, there has never been anything like the original version of “Roots.”

Broadcast in 1977, the miniseries based on Alex Haley’s account of tracing his enslaved ancestor Kunta Kinte back to Africa was watched by 100 million people and triggered a cultural explosion.

Since then, it has been impossible to think of America without considering slavery and racism.

Millions of people — black and white — have dug into their own family’s origins, creating a genealogical industry based on DNA testing and archival research.

The self-serving myth that something other than slavery was the cause of the Civil War is gone with the wind, even though hard-core apologists for the Confederacy continue to insist otherwise. The debate has been especially heated here in Virginia, the former secessionist state where much of “Roots” is set.

And yet, for all its impact during the past four decades, the original series seems to have lost much of its emotional wallop. That is, in part, because the story and its iconic characters — Fiddler, Kizzy and Chicken George — have become so familiar that they have lost their capacity to shock.

But it is also because America has changed so much since “Roots” made its debut. Back then, the notion that an African-American could be president was laughable. Today, President Obama is nearing the end of two terms in the White House. Back then, the dominant racial issue was busing. Today, it is police killings of unarmed young men. Movies such as “Django Unchained” and “12 Years a Slave” have been big hits, occupying portions of the artistic examination of slavery that “Roots” once had all to itself.

Such huge shifts in the racial zeitgeist called for a new, updated rendition of the classic that would appeal to a rising generation. In a recent interview, LeVar Burton, who starred as Kunta Kinte in the 1977 version, described a conversation with David Wolper, the son of Mark Wolper, executive director of the pioneering production. “He explained that he had attempted to show the original to his children, and the response was very lukewarm,” said Mr. Burton. “They understood why ‘Roots’ was important to him, but they didn’t feel it had much relevance to them.”

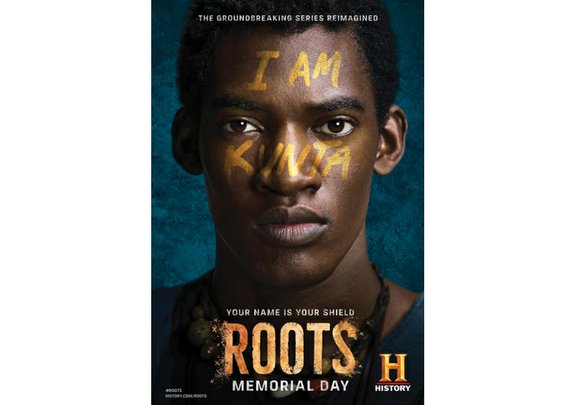

The result of those conversations is the astonishing new four-part retelling of “Roots” that debuted on Memorial Day on the History, A&E and Lifetime cable channels. The new version tells much the same story as its iconic predecessor, but in a more nuanced and complicated way. Like the original series, the new version is a mixture of fact and fiction, a cinematic version of a historical novel, rather than a work of history.

In this new version, Juffure, from which Kunta was kidnapped, is no longer a simple African village, but a metropolis throbbing with commerce in, among other things, slaves. Kunta, played with compelling intensity by rising star Malachi Kirby, is no longer a stripling out to gather firewood, but a fierce Mandinka horse warrior who, once brought in chains to America, not only repeatedly tries to escape, but also kills several white people in the process. Stunning performances by Forest Whitaker (Fiddler), Regé-Jean Page (Chicken George) and Laurence Fishburne (Alex Haley) provide subtle context.

As in the original, Kunta Kinte is finally broken and forced to accept the slave name “Toby” by a brutal horsewhipping at the hand of a white overseer. Like many scenes in the new version — such as the shooting in the back of a runaway slave that evokes contemporary incidents of police violence or the massacre by Confederate soldiers of hundreds of black Union fighters after the battle of Fort Pillow in Tennessee — the depiction of this pivotal moment is so harrowing that many viewers will find it painful to watch.

But they should make the effort. The new version may attract fewer viewers — roughly 5.3 million watched the first installment on May 31 — but it is a powerful and moving production that will reinforce the legacy of the original and make it relevant to a new generation.

In the end, it matters little if the new series adheres strictly to the mundane facts of our history, so long as it captures the spirit of the times. LeVar Burton says that he wants the new production to stir a new conversation in which “it is absolutely, unavoidably clear that America today is directly related to America of the antebellum South and the slave trade.”

This is a “Roots” for today and the next 40 years.