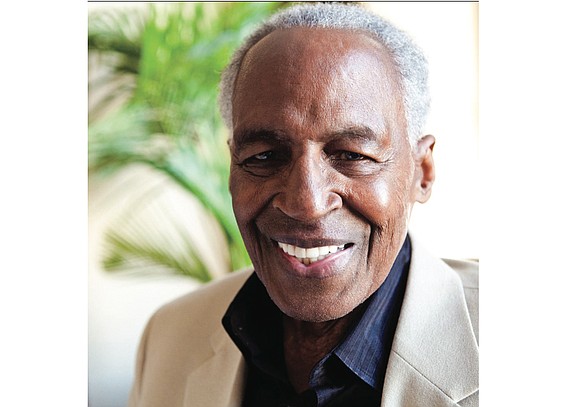

Robert Guillaume, stage, screen, Emmy TV star, dies at 89

Free Press wire reports | 11/3/2017, 1:38 a.m.

Free Press wire reports

LOS ANGELES

Robert Guillaume rose from squalid beginnings in St. Louis slums to become a star in stage musicals and win Emmy Awards for his portrayal of the sharp-tongued butler in the TV sitcoms “Soap” and “Benson.”

His stage, screen and TV achievements are being remembered following his death Tuesday, Oct. 24, 2017, at his California home near Hollywood. He was 89.

His widow, Donna Brown Guillaume, said he had been battling prostate cancer.

He earned his TV roles after playing Nathan Detroit in the first all-black version of “Guys and Dolls” on Broadway, earning a Tony nomination in 1977.

He also was the voice of the shaman Rafiki in the film version of “The Lion King” and won a Grammy in 1995 for his narration of a read-aloud version of the story.

He also served as narrator for the animated HBO series “Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child,” which aired from 1995 to 2000.

Actor Josh Charles tweeted, “Robert Guillaume radiated such warmth, light, dignity, and above all, class. That smile and laugh touched us all.”

While playing in “Guys and Dolls,” Mr. Guillaume was asked to test for the role of an acerbic butler of a governor’s mansion in “Soap,” a primetime TV sitcom that satirized soap operas.

“The minute I saw the script, I knew I had a live one,” Mr. Guillaume recalled in 2001. “Every role was written against type, especially Benson, who wasn’t subservient to anyone. To me, Benson was the revenge for all those stereotyped guys who looked like Benson in the ’40s and ’50s (movies) and had to keep their mouths shut.”

The character became so popular that ABC was persuaded to launch a spinoff simply called “Benson,” which lasted from 1979 to 1986. His character went from running the kitchen for a governor to becoming a political aide to eventually becoming lieutenant governor.

After suffering a stroke in 1999 and recovering, Mr. Guillaume became a spokesman for the American Stroke Association.

While he became wealthy from his TV work, his origins were grim.

“I’m a bastard, a Catholic, the son of a prostitute, and a product of the poorest slums of St. Louis,” he wrote in the opening paragraph of his 2002 autobiography, “Guillaume: A Life.”

He was born on Nov. 30, 1927, one of four children. His mother named him Robert Peter Williams. He adopted the last name Guillaume, a French version of William, as a stage name he thought was more distinctive.

His early years were spent in a back-alley apartment without plumbing or electricity. An outhouse was shared with two dozen people, he wrote. His alcoholic mother hated him because of his dark skin, but his grandmother rescued him, taught him to read and enrolled him in a Catholic school.

Early on a rebel, he was expelled from school and then the Army. He also fathered a daughter and abandoned the child and her mother. He did the same to his first wife and two sons and to another woman and a daughter.

Before finding acting, he worked in a department store, the post office and as St. Louis’ first black streetcar motorman. Seeking something better, he enrolled at St. Louis University, excelling in philosophy and Shakespeare, and then went to Washington University in St. Louis, where a music professor trained the young man’s superb tenor voice.

After serving as an apprentice at theaters in Aspen, Colo., and Cleveland, Mr. Guillaume won roles with such touring Broadway shows as “Finian’s Rainbow,” “Golden Boy,” “Porgy and Bess” and “Purlie,” and began appearing on sitcoms such as “The Jeffersons” and “Sanford and Son.”

Mr. Guillaume’s first stable relationship came when he married TV producer Donna Brown in the mid-1980s and had a daughter, Rachel. At last he was able to shrug off the bitterness he had felt throughout his life.

“To assuage bitterness requires more than human effort,” he wrote at the end of his autobiography. “Relief comes from a source we cannot see but can only feel. I am content to call that source love.”