Decades of foresight enable Virginia to process cargo diverted from maryland after bridge collapse

Nathaniel Cline-Virginia Mercury | 4/4/2024, 6 p.m.

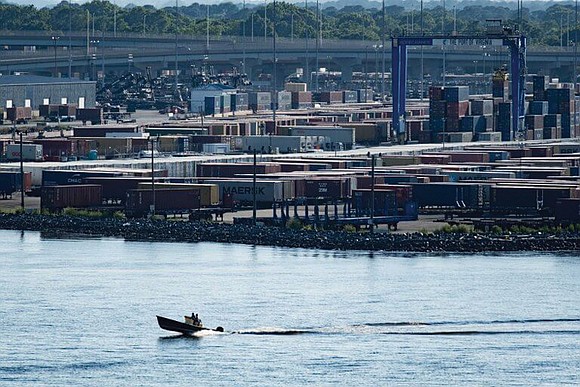

The Port of Virginia is taking on additional cargo shipments diverted from Baltimore, Md. after a massive ship crashed into the Francis Scott Key Bridge last month.

Virginia officials said the port can handle the extra workload because over 50 years ago, state and local leaders took steps to minimize any mishaps with cargo ships by building tunnels underwater and, more recently, expanding its waterways.

“The Port of Virginia has a significant amount of experience in handling surges of import and export cargo,” said Joe Harris, a spokesman for the Port of Virginia.

Mr. Harris said he is certain the “modern 21st century” port will maintain high service and efficiency levels. On Friday, March 29, Mr. Harris said it was too early to report how much cargo destined for Baltimore had been processed by the Port of Virginia. According to last May’s State of the Port, a total of 3.7 million units of cargo were processed in 2022, a 5% increase since 2021.

When the Eiffel Tower-sized Dali cargo ship lost power and crashed into the Key Bridge early on the morning of March 26, the impact had a ripple effect. Leaders and emergency response teams were forced to act quickly to rescue construction workers who were working on the bridge and were thrown into the water, and to divert vehicle traffic from the route, a major thoroughfare for travelers and goods. The bodies of two construction workers were retrieved from the water; four others are presumed dead.

Due to the bridge’s collapse, Maryland initially suspended operations at the Port of Baltimore and ship operators had to seek alternatives. That is when officials at the Port of Virginia stepped in to help by servicing ocean carriers, or companies that provide maritime services for shipment, similar to other ports throughout the Mid-Atlantic.

On March 26, Mr. Harris said the Port of Virginia processed some container cargo that was bound for Baltimore at the container terminal, known as the Virginia International Gateway. Mr. Harris said the Port of Virginia anticipates these diverted volumes to increase, but it is too early to discuss specific impacts on the port’s operation.

Gov. Glenn Youngkin told reporters on the same day that state transportation agencies in Maryland and Virginia were working to make sure there is “uniform signage” along the Chesapeake Bay for ocean carriers. The governor said his administration also offered any support or emergency assistance to Maryland’s administration.

While no ocean carriers cross under-span bridges in Virginia, the governor said last week that the Commonwealth inspects the bridges yearly, a fact he “personally checked” to confirm.

“We don’t have ocean-going carriers that are traversing our rivers, but this is a reminder, of course, that when a large vessel runs into a bridge, it can cause an extraordinary amount of not just damage, but tragedy and that’s something that we’re really closely paying attention to,” Gov. Youngkin said.

The tunnels

Within the past 70 years, Virginia leaders have constructed tunnels and bridges to accommodate cars, boats and ships to cross the Elizabeth River and the Chesapeake Bay.

Jeff Holland, executive director for the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel District, said in the 1950s, area leaders needed to minimize travel times to stimulate economic commerce. They also needed to ensure that any crossing they made allowed large vessels enough clearance to travel over the main channels. A ferry was used for these purposes at the time, but it had drawbacks.

On average, he said the ferry system took an hour and 45 minutes to two hours to cross. Travelers would wait for a ferry for up to half a day on weekends to travel and a full day on holidays.

In 1956, the General Assembly authorized the construction of a 17.6-mile fixed crossing in the Chesapeake Bay, which included three low bridges and two tunnels. The project cost approximately $139 million.

Following its opening in 1964, the bridge was named after Lucius J. Kellam Jr., the Chesapeake Bay Ferry Commission chair who spearheaded the bridge-tunnel project connecting Virginia Beach to Cape Charles in Northampton County on the Eastern Shore.

Mr. Holland said leaders in the 1950s had two benefits when building the tunnels: low cost and support from the Navy.

The director said engineers projected the cost of building the tunnels to be less than constructing bridges in the 1950s. He said today, the cost of constructing tunnels is approximately twice as much as it was back then.

Mr. Holland said leaders also considered that the tunnels would allow “unmitigated” access to the harbors.

The United States Navy, whose Norfolk naval base is the largest in the world, “certainly applauded” the tunnels, Mr. Holland added, because they offered “unhindered” access, even if a bridge were to collapse.

Mr. Holland said the construction of the bridge tunnel has resulted in “huge efficiency savings” in travel time. Approximately 175,000 to 200,000 vehicles annually traveled across the Bay in 1964, compared to the current annual average of four million vehicles.