We shall overcome

Charleston church massacre spurs removal of racist symbols

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 6/26/2015, 11:02 p.m. | Updated on 6/26/2015, 11:03 p.m.

The nation is still reeling from the bloodbath in a historic African-American church in Charleston, S.C. — evidence of the racial hatred that lies just below the surface.

In one of the most deadly domestic terrorist hate crimes in recent years, a white supremacist spent an hour in Bible study last week and then pulled out a gun and began blasting those who had welcomed him into their midst at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

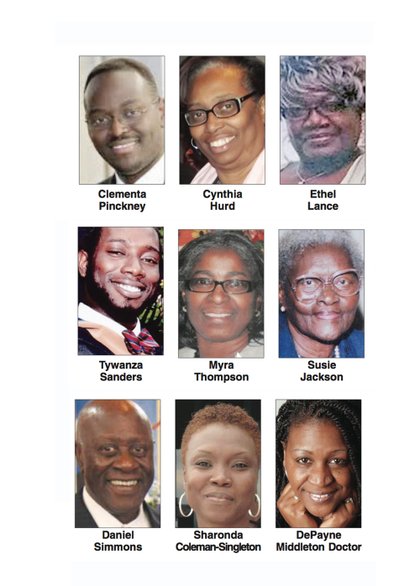

He killed nine people, including the pastor, the Rev. Clementa C. Pinckney, 41, a much admired and long-serving South Carolina state senator who fought for the underserved. Six women and two other men, ranging in age from 26 to 87, also died in the rampage.

The perpetrator, 21-year-old Dylann Storm Roof, was captured a day later, on June 18, more than 100 miles away in Shelby, N.C., after a sharp-eyed florist in the small town spotted him and his car.

President Obama expressed the feelings of many when he said, “There is something particularly heartbreaking with (this) happening in a place in which we seek solace and we seek peace.”

The outrage over Mr. Roof’s racially motivated attack has given new energy to longstanding efforts to eliminate symbols of the hate he embodies, most notably the Confederate flag. Proposals to remove the flag from statehouses, state license plates and store shelves are winning wide support in numerous states.

The atrocity immediately stirred memories of the outrages of the Civil Rights era. Most cited — the Ku Klux Klan bombing of a Birmingham, Ala., church. Four little girls were killed and dozens of other worshippers and passers-by were maimed and injured.

The purpose of these acts: To terrorize African-Americans and halt their civil rights efforts.

The shooter in Charleston began a racial rant as he fired on the unsuspecting church members. A survivor, who said Mr. Roof spared her so she could tell what happened, reported him saying: “You rape our women, and you’re taking over our country. And you have to go.”

This new act of domestic terrorism comes on the heels of the “Black Lives Matter” campaign — prompted by police killings of unarmed black men. One took place in early April in North Charleston, a few miles from the AME church whose founders included Denmark Vesey, who plotted a slave uprising that ultimately failed nearly 200 years ago.

For many, the outrageous attack was more than a hit against peaceable people engaged in expressing their faith; this was a hit against a symbol of black freedom.

“That’s why so many folks are so upset. This is a church that represents so much about the rich history and tradition of African-Americans,” said Dr. Robert Greene, who teaches the history of the 20th-century South at the University of South Carolina.

The saving balm from this horrific slaughter has been the almost universal reaction of grief, support, unity and love — clearly not what the murderer hoped for.

He told authorities he wanted to trigger a “race war.”

Instead, in Richmond and elsewhere, he has sparked vigils and conversations about faith and forgiveness.

The families of the martyrs helped make it happen. At a time when fear, religious doubt and the desire for revenge might have been expected, the response to Mr. Roof’s hate was love.

“I forgive you,” Nadine Collier, daughter of slain church member Ethel Lance, told Mr. Roof when he was arraigned Friday, typical of the views of family members. “I will never hold her again. But I forgive you, and may God have mercy on your soul.”

“Lots of folks expected us to do something strange and break out in a riot. Well they just don’t know us,” the Rev. Norvel Goff preached Sunday in leading the reopening of the church. “We have shown how we, as a group, can come together and pray and work out things.”

More incredibly, is the resolve Mr. Roof has created to banish the most notorious symbol of racial hatred — the Confederate battle flag — the symbol of the Southern fight for slavery during the Civil War, of the Klan’s efforts to stomp on black freedom during Reconstruction and beyond and the Jim Crow fight to maintain white supremacy through separation of the races.

Just a few social media images of Mr. Roof posing with the infamous Stars and Bars has been enough to swiftly change attitudes about the flag and regenerate talk in Richmond and elsewhere about removing statues and other symbols of the Confederate and Jim Crow periods.

From Virginia to Alabama and beyond, governors and other state leaders are hustling to remove the Confederate flag from license plates and take it down from public flag posts to show support for the Charleston church martyrs and their families.

Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe announced Tuesday he would join three other states in eliminating the Confederate flag from vanity license plates, though he rejected calls to get rid of the huge statues of traitorous Confederates inside and around the Capitol who sought to dismantle the Union in an effort to protect the buying and selling of human beings.

Alabama’s governor just removed the flag from the Capitol in Montgomery; Mississippi is considering eliminating the Confederate symbol from its flag.

Even South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, who previously rebuffed NAACP calls to remove the flag from the statehouse in Columbia, now wants this symbol of hatred removed from public property. She is winning support in the state legislature for such action. Two-thirds of the South Carolina House and Senate would need to approve the removal.

Meanwhile, giant retailers are rushing to distance themselves from the Confederate flag that they previously profited from selling. Walmart, Amazon, Sears, Google, eBay and a host of others are pulling the symbol of hatred off their shelves and Internet sales sites.

And flag manufacturing companies, north and south, are promising to stop making replicas of the flag, now viewing the banner as a symbol of hatred and division to be eradicated.

Still, fringe groups are angry, including the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the Virginia Flaggers, who eagerly flaunt the flag.

But most people who once embraced the flag as a symbol of “heritage, not hate” suddenly have been forced to recognize how the Confederate flag is seen through others’ eyes.

Many have seen the light, transformed in part by the attitude of the Charleston victims’ family members.

The ripples from this tragedy, though, will only travel so far. Neither Virginia nor Richmond’s government is likely to tear down any Confederate statues. Nor is the Richmond School Board likely to replace the names of Confederate leaders on school buildings. The majority-black policymaking body has never considered such action.

President Obama wants to see the outrage over the Confederate flag provide fuel to power changes in gun laws, though he has few expectations that will happen.

In his remarks about the Charleston massacre, he said that he has had to speak too often about multiple murders during his tenure. As was the case before, he said, “We do know that once again, innocent people were killed, in part, because someone who wanted to inflict harm had no trouble getting his hands on a gun.

“Now is the time for mourning and for healing,” he said. “But let’s be clear. At some point, we as a country will have to reckon with the fact that this type of mass violence does not happen in other advanced countries.

“It doesn’t happen in other places with this kind of frequency. And it is in our power to do something about it.”