Ronald Acuna hopes to bat his way into Hall of Fame

Fred Jeter | 8/16/2019, 6 a.m.

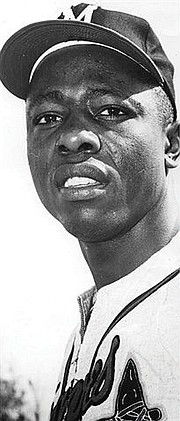

Hank Aaron debuted with the Milwaukee Braves in 1954 and embarked on arguably one of the most illustrious careers in baseball lore.

Ronald Acuna Jr., who broke in with the Atlanta Braves last season, shows signs of following a similarly star-lit course.

“If I put Aaron and Acuna side by side, I think they would be the same,” Ralph Garr told MLB.com.

Garr, who played two seasons in Richmond, was a teammate of Aaron’s and more recently was a hitting instructor with the Braves.

“Unless Acuna gets hurt or something, he has a chance to be in the Hall of Fame,” Garr said.

Both Aaron, from Mobile, Ala., and Acuna, who is from Venezuela, entered the major leagues at age 20, and both broke in with a bang — or more to the point, with a loud crack of the bat.

As a rookie in 1954, Aaron hit .280, with 13 homers and 69 runs batted in for 122 games. He finished his career with home run (755) and RBI (2,297) records at the time.

Aaron has a spotless reputation in a sport stained by players who used performance- enhancing drugs. He was a first-ballot Hall of Fame selection in 1982, with 92 percent of votes cast.

Acuna, a muscular 6 feet, 205 pounds, was a near unanimous Rookie of the Year honoree in 2018, hitting .293, with 26 homers and 64 RBI in 111 games.

There has been no “sophomore slump” for Acuna. As a National League All-Star starter, Acuna was hitting .296 with 32 homers, 78 RBI and 28 stolen bases in games this season through Aug. 10.

He’s a clear MVP candidate, along with teammate Freddie Freeman.

Acuna was voted in as a National League All-Star Game starter in July and was selected to swing in the Home Run Derby.

Comparisons go beyond just offense for these right-handed sluggers.

Both are outfielders. Aaron played a flawless right field; speedy Acuna patrols left field.

Each has a popular nickname. Aaron was “The Hammer;” Acuna is “El Abusador,” Spanish for the abuser.

Neither was drafted. Aaron signed at age 17 with the Negro League Indianapo- lis Clowns for $300 per month. Also at 17, Acuna was an Atlanta Braves free-agent signee, with a $100,000 bonus.

The baseball draft wasn’t installed until 1965. Venezuelans are not eligible for the draft.

Acuna’s nickname fits. Few can “abuse” a pitcher like Acuna, who unloaded an other-worldly 462-foot home run —112 mph exit velocity — in an April game against the New York Mets.

“He’s special,” Atlanta Braves Manager Brian Snitker said of Acuna. “He’s not really trying to be great. He’s just doing his thing.”

Aaron comparisons aside, Acuna is a front-row reason why Atlanta won the NL East a year ago and why the team is well out in front this season.

Acuna’s success isn’t surprising, considering Baseball America ranked him a top prospect in all of baseball heading into the 2018 season. His family tree seems to be made of wooden bats. He was never far from a diamond growing up in the port city La Guaira, Venezuela.

Acuna is the eldest of four sons. His father, Ronald Sr., and grandfather, Romauldo Blanco, both played minor league baseball in the states. An uncle, Jose Escobar, played for the Cleveland Indians in 1991. Four cousins, Vicente Campos, Alcides Escobar, Edwin Escobar and Kelvim Escobar, all played in the majors.

Hank Aaron played big league baseball from 1954 to 1976 with stunning talent and consistency. It’s a towering — some might say impossible — task to follow, even for one as gifted as Acuna.

“El Abusador” has dazzled so far, but now comes the greater challenge — maintaining that pace.

“Acuna’s a great player, but you never know,” Garr said. “We’ll see what happens. He has 20 or so more years to get it done.”