400 years

8/23/2019, 6 a.m.

“The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.” — Ida B. Wells

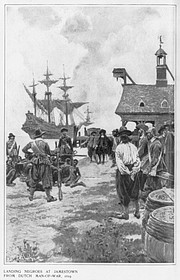

We pay tribute here to the “20 And odd Negroes” who, 400 years ago in late August 1619, ended up on Virginia’s shores at Point Comfort in what is now Hampton.

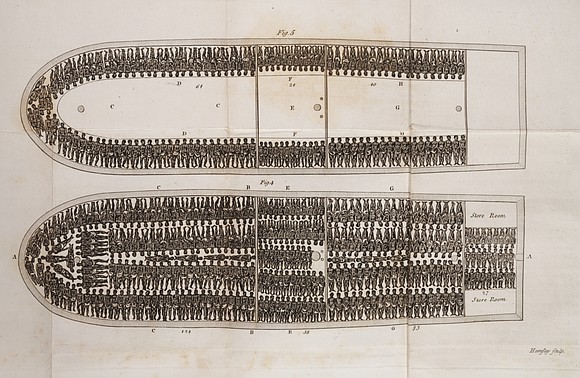

According to historians, these souls were among 350 men and women captured in Central Africa and put on a Portuguese ship bound for Mexico. The Portuguese vessel was attacked in the Gulf of Mexico by two English pirate ships, the White Lion and the Treasurer, and 50 to 60 of the Africans were taken. Later caught in a storm, the White Lion docked at Point Comfort, where 20 or more Africans were traded for food.

That, essentially, began the slave trade in English North America. By the mid-1800s, more than 12 million Africans were captured, sold and transported across the Atlantic to the Americas and the Caribbean.

In Virginia, many of the early Africans were enslaved, while some became free. However, laws enacted by 1664 put into place the legal framework that barred people of African descent from ever being free.

Ironically, Fort Monroe, a Union stronghold located at Point Comfort, would later play a major role in the emancipation of black people during the Civil War, which brought an end to slavery in 1865, along with the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in December of that year.

This weekend’s events in and around Hampton commemorate those first Africans who, by stroke of happenstance or misfortune, wound up in a land built on the promise of opportunity and the principle of freedom, but for whom both would be denied. The following centuries would be marked by the continuing struggle for freedom by people of strong will and endurance.

As we reflect on this moment in time, and the long and stony road for us as a people of African descent and as individuals, let us remember that slavery does not define us. Our history began long before the White Lion and 1619, and our legacy extends well beyond bondage.

Truly, the damage of slavery remains embedded in the psyche of black people and white people alike, its remnants wrapped in many of today’s unjust laws, policies and practices and erupting in the violent acts of domestic terrorists.

What have we as Virginians, as Americans, learned from this 400-year history? What can we do to better shape our community, our city, our state and our nation into a more equitable, peaceful and just place for people today and for those who will come after us?

Each day we are writing what will become tomorrow’s history. What story will they tell about us in the next 400 years?