Muslim superhero who fought Nazis in comic books making a comeback

Religion News Service | 1/4/2019, 6 a.m.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

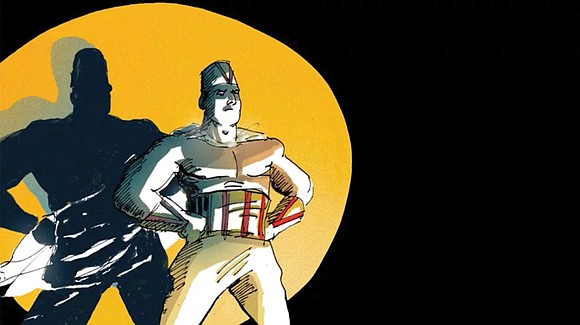

In 1944, the world met Kismet, an Algerian superhero who fought against fascists in southern France while wearing a yellow fez.

He punched Nazis, foiled Hitler’s plans and came to the aid of civilians in need.

“The conquered people of Europe carry on their ceaseless struggle against the forces of tyranny,” reads the introduction to one of his adventures from Elliot Publications. “And fighting by their side, lending the power of his great mind and the force of his mighty fists, is Kismet, Man of Fate.”

After four issues, however, Kismet disappeared and was forgotten.

Seven decades later, Kismet is making a comeback in a new graphic novel from author A. David Lewis. The story drops Kismet in Boston as the city heals from the aftermath of 2013’s Boston Marathon bombing.

Mr. Lewis said that Kismet deserved a fresh start.

“He was basically abandoned to the public domain,” Mr. Lewis told Religion News Service in an interview at the comic store Comicazi, where he was signing books for fans just a few miles north of Boston. “That saddened me because there was this strange nobility about his character that felt anachronistic.”

Kismet is a reboot of what appears to be the first identified Muslim superhero character published in English.

Most Muslims in the Golden Age of comics were written as flat, one-dimensional characters, or in sloppy ways that fed into stereotypes and conflated Arabs and Muslims, Mr. Lewis said.

But, he said, Kismet was given some level of dignity.

“And I saw the potential in that,” Mr. Lewis said.

Other Muslim superheroes have suffered a similar fate as Kismet. In 2000, D.C. introduced a Turkish character, Janissary, whose last appearance was in 2007. Marvel character Monet St. Croix debuted in 1994 but wasn’t identified as a Muslim character until 2011. In 1995, Marvel introduced Syrian superhero Batal and immediately killed him off.

Rebooting Kismet felt like an opportunity to do better.

Mr. Lewis rattled off a list of common tropes about Muslim characters he hoped to avoid with his character: The “noble savage” who is uncorrupted by modern civilization; the mystical Muslim superhero; the docile Muslim woman; the perishable “cannon fodder;” and, more broadly, Muslim characters being carelessly boiled down to a nebulous racial and religious mass.

For Mr. Lewis, writing a Muslim superhero was also an opportunity to address the connection between superhuman ability and cosmology. Do the powers to, say, fly or manipulate fire come from God?

Those questions appeal to Mr. Lewis, who has a doctorate in religion and literature. The author of “American Comics, Literary Theory, and Religion: The Superhero Afterlife,” Mr. Lewis has spent years grappling with the connection between theology and comics.

He points to the Quranic story of the prophet Yusuf, which parallels the Old Testament’s Joseph. When Joseph was trapped in the Pharaoh’s prison, he despaired, Mr. Lewis said.

“But when Yusuf was trapped, he kept it together because he had faith in God’s will,” Mr. Lewis said. “That’s the sort of strength that I give to Kismet.”

The original Kismet had no special superpowers; he fought using just his hands and what the character says is “the freedom given to me by Allah and the Prophet.”

That’s true in Mr. Lewis’ version of the character as well.

“He doesn’t ultimately save the day because he’s the strongest or is the better hero,” Lewis said. “He wins because he has faith.”

Mr. Lewis grew up in a Jewish family in Framingham, Mass., and converted to Islam 12 years ago. He initially saw Kismet’s story as a way to address the issue of Islamophobia. But by the time he began working the Kismet graphic novel for his publisher, A Wave Blue World, another thread of Kismet’s story seemed just as timely — the threat of domestic fascism and a new white supremacy movement.

While his hero punches Nazis in comics, Mr. Lewis tries to imbue the story with a more complicated perspective. When a video of a hooded protester punching white nationalist leader Richard Spencer in the face went viral early last year, Mr. Lewis was not on board. He even wrote an article for ComicsBeat.com saying as much: “We cannot already be at our last resort, namely violence,” he argued in January 2017. “I’m not waiting until the 11th hour, but the Doomsday Clock still has a goodly number of ticks left in it.”

But after watching Mr. Spencer lead a crowd of neo-Nazis marching through Charlottesville, with torches a few month later in August 2017, he reflected on the Quranic guidance in favor of self-defense. “And then I realized that we were there,” he said. “Then I realized it’s time to hit back.”

Mr. Lewis, who also produces free comics for Syrian refugee children as head of the nonprofit Comics for Youth Refugees Incorporated Collective, is clear that Kismet’s return is not a call for violence. “This is just saying that it’s time to pick a side.”

The new graphic novel isn’t the first time that Mr. Lewis has written stories about Kismet, whom he first discovered while doing his academic research. He published two short stories with the character in 2015 and 2016, after a crowdfunding campaign. A Wave Blue World then commissioned him to produce a recurring web series with Kismet last year, before asking for a full-length graphic novel.

The new Kismet universe, set in Boston, incorporates American Muslim history — the Council on American-Islamic Relations, Thomas Jefferson’s Quran, the enslaved African Muslims, the fact that the United States’ first-ever treaty was with Muslim-majority Tripoli — and Boston’s local Muslim landscape into the lore of Kismet’s story.

A Wave Blue World’s publisher, Tyler Chin-Tanner, said the time is right for Kismet’s story.

“Comics have always had a strong link to politics and world events, going back to their roots during World War II,” he said. “And if you take a look at what’s going on in the world around us today, this is no time to ignore the lessons history has taught us.”

There are signs that a Muslim superhero comic can be successful. G. Willow Wilson’s Ms. Marvel, alter ego of fictional Pakistani-American Kamala Khan, has been a breakout success. (Award-winning Muslim writer Saladin Ahmed will take over the Ms. Marvel series, which originally launched in 2014, with the upcoming release of “The Magnificent Ms. Marvel.”)

But Mr. Lewis does not want Kismet to be “just” a Muslim superhero, nor does he want him to be a banner for Islam in any way, he told Columbia University students during a recent panel.

Mr. Lewis drew on the sparse details of the original storyline to flesh out Kismet’s character and back story, giving him a real name, occupation, hometown, family and his own crises of faith: Khalil Qisma, a jail guard from Algiers with a wife and children, who says he prays “when he can” and wonders about his moral and religious imperatives to fight for justice. And then by setting up multiple Muslim characters who all have unique voices, backgrounds and expressions of faith, he was able to show degrees of Muslim religiosity, he said.

“It was important to show that Muslim identity is multivalent as well as expressed in so many different ways,” Lewis said. “And I’m not capturing them all, but I hope that I’m opening the door wider to all of these experiences.”