Author Ta-Nehisi Coates deconstructs power: 'The South won the war of aesthetics'

Christopher Brown/Capital News Service | 10/31/2019, 6 p.m.

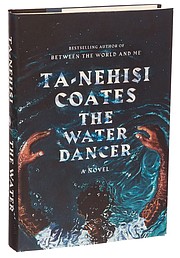

Author and Maryland native Ta-Nehisi Coates visited Richmond last week to discuss emancipation and to promote his New York Times best-seller, “The Water Dancer.”

The book is set in Virginia, but his work isn’t the only connection to the Old Dominion. Mr. Coates recently found out that one of his ancestors was enslaved outside of Petersburg.

“It’s of special meaning to be here in the capital of the Confederacy,” Mr. Coates told the crowd.

He pointed out that many people can trace their ancestry to Virginia because of the slave trade. “My story of having my ancestors being from Virginia is actually not that original,” he said.

Christy Coleman, chief executive officer of the American Civil War Museum, and Dr. Manisha Sinha, a professor at the University of Connecticut, joined Mr. Coates on stage Oct. 25 before a sold-out crowd of almost 500 people at the Virginia Museum of History & Culture.

The evening was part of the museum’s ongoing exhibition “Determined: The 400-Year Struggle for Black Equality” and was co-sponsored by the American Civil War Museum.

The discussion, “Legacies of Emancipation,” exam- ined the history of enslaved African-Americans during the 1800s leading up to emancipation and the shift from enslavement to freedom.

Dr. Sinha, who teaches 19th century African-American and feminism history, said the emancipation of the enslaved in America was not just a “singular event, but a process that involves many social actors.”

“When you think about emancipation in that manner, you can actually uncover the efforts of African-Americans,” Dr. Sinha said.

Mr. Coates’ book examines the idea: “What if memory had the power to transport enslaved people to freedom?” Hiram Walker, the book’s protagonist, is an enslaved African-American with a superhuman ability allowing him to travel long distances through water. His powers are triggered only through memories of his mother, who was sold and separated from him when he was a child.

According to Mr. Coates, the idea of creating a black superhero during the antebellum South was inspired by the “war of aesthetics and beauty” that the Confederates won. He questioned the creation of an “Arthurian Camelot,” a fictional castle and a symbol of King Arthur’s story, that revered and memorialized Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee.

“On one level, there was a robbery of history. But on another level, it was the idea that somehow fighting for the right to steal labor from people and sell people ...should somehow be depicted beautifully,” Mr. Coates said.

After an hourlong discussion, the panel took questions from the audience.

Virginia Commonwealth University employee and attendee Chante Holt asked what the state should do to combat the current high rate of evictions — with five Virginia cities in the top 10 nationally — that disproportionately affect people of color.

“Give them money,” Mr. Coates responded, adding that “you are robbing people” if they are taxed equally but only given a “sliver of the same resources.” Brandy Akins, who works in human resources at Altria, responded to the statement Mr. Coates made about the maintenance of power being “deeply tied to forgetting.” “The fact that we don’t remember Reconstruction the way it actually happened is not an accident,” Mr. Coates said.

Ms. Akins told Mr. Coates some people in her social group believe the period before desegregation “sounds like it was better than the situation we’re in now.”

“To not live in that world and to say that this world is worse, I mean, it just looks like you’re spitting on people,” Mr. Coates said. “If it was so much better, why would children march in the street, getting sprayed with fire hoses, having dogs sicced on them.

“The era of segregation was open terrorism,” Mr. Coates added.

Afterward, people explored the museum’s exhibit that opened on June 22, the day the street where the museum is located was renamed for Arthur Ashe in honor of the late tennis legend and Richmond native.

The exhibit, which runs through March 29, chronicles the black experience from 1619 to the present day through interactive exhibits set in four chronological sections: the Colonial period; American Revolution through the Civil War; Reconstruction through World War II; and the Civil Rights Movement through today.