Unsung civil rights pioneer Gloria Richardson dies at 99

Free Press wire reports | 7/22/2021, 6 p.m.

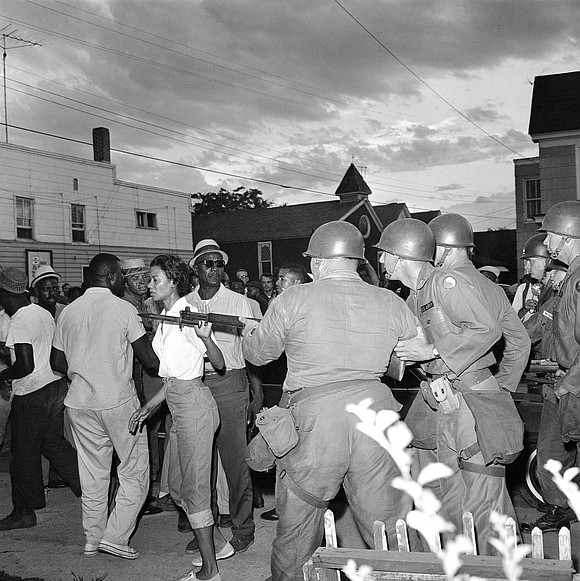

ANNAPOLIS, Md. - Gloria Richardson, an influential yet largely unsung civil rights pioneer whose determination not to back down while protesting racial inequality was captured in a photograph as she pushed away the bayonet of a National Guardsman, has died.

She was 99.

Tya Young, her granddaughter, said Mrs. Richardson died in her sleep July 15, 2021, in New York and had not been ill. Ms. Young said while her grandmother was at the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement, she didn’t seek praise or recognition.

“She did it because it needed to be done, and she was born a leader,” Ms. Young said.

Mrs. Richardson was one of the nation’s leading female civil rights activists and inspired younger activists who went on to protest racial inequality in the late 1960s and into the 1970s.

She was on the stage at the pivotal March on Washington in 1963 as one of six women listed as “fighters for freedom” on the program. However, she was only allowed to say “hello” before the microphone was taken.

The male-centric Black Power movement and the fact that Mrs. Richardson’s leadership in Cambridge, Md., lasted about three years may have obscured how influential she was, but she was well-known in Black America, said Joseph R. Fitzgerald, who wrote a 2018 biography on Mrs. Richardson titled “The Struggle is Eternal: Gloria Richardson and Black Liberation.”

“She was only active for approximately three years, but during that time she was literally front and center in a high-stakes Black liberation campaign, and she’s being threatened,” Mr. Fitzgerald said. “She’s got white supremacist terrorists threatening her, calling her house, threatening her with her life.”

She was the first woman to lead a prolonged grassroots civil rights action outside the Deep South. In 1962, she helped organized and led the Cambridge Movement on Maryland’s Eastern Shore with sit-ins to desegregate restaurants, bowling alleys and movie theaters.

Mrs. Richardson became the leader of demonstrations over bread and butter economic issues like jobs, health care access and sufficient housing.

Mrs. Richardson was born in Baltimore and later lived in Cambridge in Maryland’s Dorchester County — the same county where Harriet Tubman was born. She entered Howard University when she was 16. During her years in Washington, she began to protest segregation at a drug store.

In 1962, Richardson attended the meeting of the Stu- dent Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Atlanta and later joined the board.

In the summer of 1963, after peaceful sit-ins turned violent in Cambridge, Maryland Gov. J. Millard Tawes declared martial law. When Cambridge Mayor Calvin Mowbray asked Mrs. Richardson to halt the demonstrations in exchange for an end to the arrests of Black protesters, she declined

to do so. On June 11, rioting by white supremacists erupted and Gov. Tawes called in the National Guard.

While the city was still under National Guard presence, Mrs. Richardson met with U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy to negotiate what became informally known as the “Treaty of Cambridge.” It ordered equal access to public accommodations in Cambridge in return for a one-year moratorium on demonstrations.

Mrs. Richardson was a signatory to the treaty, but she had never agreed to end the demonstrations. It was only the passage of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 that began to resolve issues at the local level.

Mrs. Richardson resigned from Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee in the summer of 1964. Divorced from her first husband, she married photographer Frank Dandridge and moved to New York where she worked a variety of jobs, including with the National Council for Negro Women.

She is survived by her daughters, Donna Orange and Tamara Richardson, and granddaughters Tya Young and Michelle Price.