Opponents fear Main Street Station plans will run over slave memorial

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 12/1/2017, 6:49 p.m.

Hopes of creating a memorial park in Shockoe Bottom recalling Richmond’s role as a center of the slave trade appear to conflict with efforts to make Main Street Station a more significant passenger rail stop.

Mayor Levar M. Stoney is raising apprehension among advocates of the memorial park, including 2nd District City Councilwoman Kim B. Gray and the National Trust for Historic Preservation, who believe he is ignoring the opportunity to bring national attention to Richmond’s pre-Civil War history and the African-Americans who were once bought and sold like cattle.

The mayor, who insists that the station and Richmond’s slave history can coexist, raised concern by throwing his support to a draft federal-state environmental plan that calls for expanding both rail service and the footprint of the station should higher speed rail ever materialize between Richmond and Washington.

Such a plan is still a distant prospect given the projected $5 billion cost. But under the state’s preferred plan, Main Street Station would be a stop for virtually all north-south trains.

Improvements to tracks and stations in the Richmond area alone are projected to cost at least $1.5 billion to turn the Richmond-D.C. run into a two-hour train trip rather than the three hours it now takes.

Catching advocates of the memorial park off guard, Mayor Stoney issued a letter Nov. 1 to the state Department of Rail and Public Transportation.

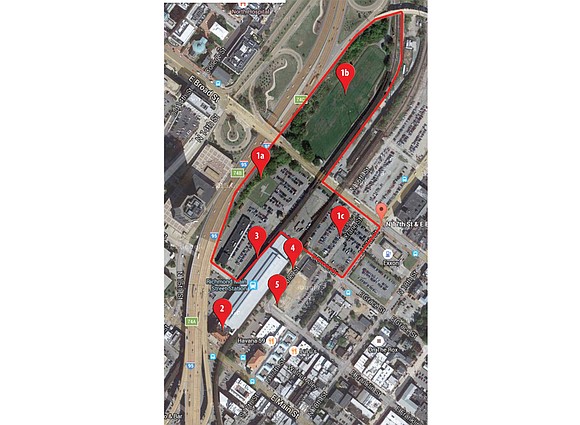

In it, he put the city on record as endorsing the state’s preferred plan to boost Main Street Station as outlined in a just-released draft environmental report. The proposal calls for adding new tracks, station parking and passenger platforms that would extend into the area proposed for the memorial park.

Advocates want to create the memorial park on 4 acres bounded by the current train tracks, Broad, 17th and Grace streets.

Mayor Stoney also called on the state to study installing additional infrastructure to enable the station to offer baggage service, now only available at Amtrak’s other area station located near Staples Mill Road and Glenside Drive in Henrico County.

Despite his inaugural pledge 10 months ago to create a new era of partnership with City Council, the mayor did not consult with or seek the approval of the council before issuing the letter.

Ms. Gray considers the mayor’s decision to act before talking with the council “outrageous.”

She agrees that previous councils have endorsed the concept of expanding the station in Shockoe Bottom, but she argues that the council has not discussed the impact such an expansion would have on the history of slavery.

She opposes any changes to Main Street Station that could impact the area that more than 150 years ago housed slave jails and auction blocks. Those buildings were razed long ago; the area is now covered by parking lots and fill dirt with any residue from the historical sites at least 12 feet below ground.

Still, Ms. Gray notes that the draft environmental report notes in one appendix that there “is a high probability” of finding “intact remains” located on land next to the station. That land would be needed to support new tracks and baggage infrastructure under the expansion plan.

She is upset that anyone — particularly an African-American mayor, she said — would want to “desecrate sacred ground. This is wrong, just wrong.”

In her view, station growth would attract hotels and other infrastructure that are likely to eliminate, isolate or restrict efforts to ensure more attention is paid to the history of slavery and the horrible conditions the enslaved endured.

The mayor noted the draft report shows the proposed station changes would not impact two key historic sites that have been the focus of city efforts to memorialize slavery.

One is Lumpkin’s Jail, or the Devil’s Half-Acre, a notorious holding cell for slaves awaiting auction before the Civil War and an early site after the war for a school for newly emancipated slaves that ultimately became Virginia Union University.

The other site is the separate African Burial Ground. Lumpkin’s Jail sits west of the station near Interstate 95 and the burial ground sits north of Broad Street. Both are outside areas planned for station growth.

City Councilwoman Ellen F. Robertson, whose 6th District includes the train station and the slavery sites, has been a station advocate and backs the mayor’s position, given that both Lumpkin’s Jail and the burial ground would be protected.

That’s also the position of Delegate Delores L. McQuinn, chair of Richmond’s Slave Trail Commission, which has developed a trail through the city to mark where slaves once walked and is deeply involved in the city’s efforts to create a museum-style development to highlight Lumpkin’s Jail.

However, Phil Wilayto and Ana Edwards agree with Ms. Gray. The couple have led the charge for the memorial park as founders and leaders of the advocacy group Defenders of Freedom, Justice and Equality and the Sacred Ground Historical Reclamation Project.

“The mayor has shown a remarkable lack of interest in this history,” said Mr. Wilayto, who is convinced that history will be sacrificed in the name of progress.

He also is highly critical of the draft environmental report, noting that in it slavery gets short shrift. He noted that the report’s archaeological survey, as well as its list of historical resources, does not mention the Richmond Slave Trail, Richmond’s role as the nation’s second largest center for the slave trade after New Orleans or the fact that Richmond’s development was built on slavery.

“It’s appalling,” he said.

The nonprofit National Trust for Historic Preservation, which supports the memorial park, also is critical of the environmental report, saying it has failed to take into account the impacts an expanded station and increased train traffic would have on the important historical area.

The trust recently set aside $25 million to invest in preserving neglected African-American sites across the nation and named Shockoe Bottom and the history of slavery as the No. 1 priority.

Mayor Stoney believes that Richmond can have both better train service and a memorial park. His press secretary, James Nolan, in an email to the Free Press, stated, “It will be our responsibility as a city to ensure that the train project does not conflict with the future memorial park.”