Years have shown improvements for African-Americans on Washington NFL team

7/28/2017, 6:59 a.m.

Times have changed.

As the Washington NFL team commences preseason workouts at the Bon Secours Training Center, more than half of its players are African-American.

Not so in 1962, when there were just three — the first three — African-Americans wearing burgundy and gold for bigoted team owner George Preston Marshall.

Marshall became infamous, in part, for his quote, “We’ll start signing Negroes when the Harlem Globetrotters start signing whites.”

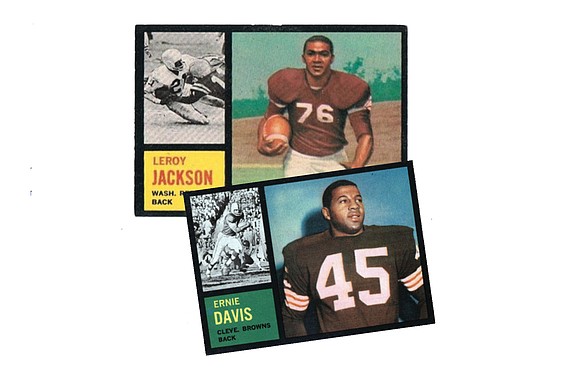

During its second season at publicly funded D.C. Stadium — later RFK Stadium — Washington grudgingly integrated its roster with wideout Bobby Mitchell, guard John Nisby and running back Leroy Jackson.

Washington was the last NFL franchise by several years to integrate. It only did so when pressure was applied by the Kennedy administration, primarily through U.S. Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall.

A haunting set of circumstances served as a prelude to the 1962 season.

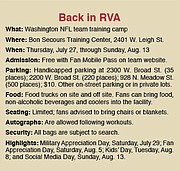

With the overall No. 1 draft pick after finishing last (1-12-1) in 196, Washington selected Ernie Davis of Syracuse University, the first African-American Heisman Trophy winner.

A native New Yorker, Davis quickly announced he would not play for Washington because of Marshall’s hateful racial stance.

Quickly, Washington traded Davis to the Cleveland Browns for Mitchell, a proven star, and newcomer Jackson, who was the Browns’ first round draft pick — 11th overall — out of Western Illinois University.

Nisby came to Washington in another trade with the Pittsburgh Steelers.

One of the NFL’s saddest stories ensued.

Davis was diagnosed with leukemia during the summer of 1962 and never played a regular season down for the Browns. He died May 18, 1963, at age 23, and is the subject of the inspiring 2008 movie, “The Express.”

In the nation’s capital, the dynamic Mitchell, who is regarded as one of football’s best receivers, went on to gain entry into the NFL Hall of Fame in 1983.

Nisby would earn his third All-Pro selection in 1962, and played two more seasons in Washington.

And Jackson?

From Chicago Heights, Ill., Jackson was a three-time Illinois state 100-yard dash champ at Bloom High School. He then enjoyed much success in football and track — 100 yards in 9.4 seconds — at Western Illinois University and became Cleveland’s top draft pick.

His rookie season in Washington went well. He rushed for 112 yards, caught passes for 253 yards and ran back kickoffs for a 27.2 yard average. In a game against Baltimore, Jackson made the longest play of the season by catching a swing pass from Norman Snead and racing 85 yards to the end zone.

Then came his second season in D.C., which was followed by controversy.

In five games before being mysteriously cut, Jackson carried just three times, but for an impressive 30 yards. He also ran back five kickoffs for a 23-yard average. There also were two fumbles.

There may have been more to this story, however. This was 1963 at the NFL’s Southern-most city. Apparently, it didn’t set well with D.C. brass when Jackson, a bachelor at the time, was caught with a white woman in his hotel room.

In a 2013 interview with Yahoo! Sports writer Les Carpenter, Jackson stated: “I think (being cut) was probably because of the woman … the interracial thing and not being able to hold onto the ball.”

He was told his release was because of the fumbles.

Jackson would never play again for Washington, despite being just one season removed from first round draft pick status and ranking among the NFL’s fastest men.

More telling, perhaps, is that no other team ever picked him up. He was through.

Was it the fumbles? Or was he blackballed?

Times have changed, fortunately.