Sculpture honors 1st Black president of U.S. college

Free Press wire reports | 12/31/2020, 6 p.m.

RUTLAND, Vt. - The first Black president of an American college is being honored with a sculpture installed in the Vermont city where he was born in 1826.

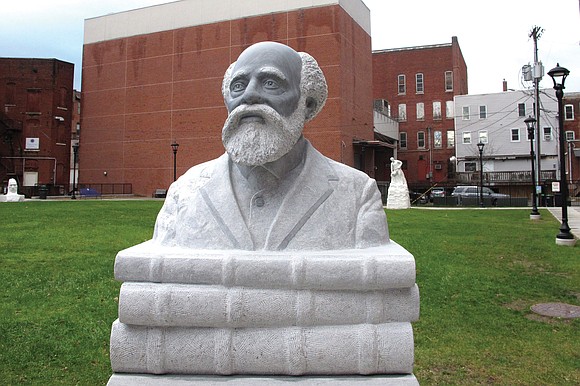

The larger-than-life marble bust of scholar Martin Henry Freeman sits on a stack of books in a downtown square as part of the Rutland Sculpture Trail.

“It’s a very soft, gentle portrayal of Martin Freeman,” said Al Wakefield, one of the sponsors of the piece that was installed in November. “I don’t know how many people remember either through historical writings what kind of person he was, but he’s depicted as a very gentle, kind, literary, artsy kind of a guy.”

It’s the eighth sculpture to be added to the city’s sculpture trail aimed at celebrating local history and drawing more people to visit the working-class community. Among the pieces is a marble relief honoring the Vermont volunteers who served in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, made up of African-Americans soldiers, during the Civil War.

Mr. Freeman attended Middlebury College in Vermont, graduating at the top of his class in 1849. His father fought in the American Revolution, one way for enslaved men to win their freedom.

Following his graduation, Mr. Freeman moved to Pittsburgh, where he taught science and mathematics at the newly opened Allegheny Institute and Mission Church north of Pittsburgh that was founded to provide elementary and advanced education to free Black people. Mr. Freeman became president of the institute, later named Avery College, in 1856.

The Freeman sculpture, designed by Mark Burnett, who is African-American, and carved by Don Ramey, was installed at a time when some cities are reconsidering and even removing sculptures or monuments related to the Confederacy or to other historical figures, such as Columbus.

Last week, Virginia removed a statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee that has represented the state in the U.S. Capitol for 111 years. A state commission has recommended replacing it with a statue of Barbara Johns, who protested conditions at her all-Black high school in 1951. Her court case became part of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision by the U.S. Supreme Court striking down racial segregation in public schools.

Mr. Wakefield, a Black man who moved to Vermont from New York City 30 years ago and whose family helped sponsor the sculpture of Mr. Freeman, said it was “really, really relevant,” in the context of the nationwide protests for racial justice and the reassessment of public statues.

Mr. Freeman’s academic success took hold at Middlebury College, where he was the only Black student in a state that was the first to abolish adult slavery in 1777. Abolitionists in town had urged Middlebury to enroll Black students as a demonstration that the school really stood against slavery, said Dr. William Hart, an emeritus professor of history of Black studies at Middlebury College.

Mr. Freeman, who supported the colonization of Liberia for Black Americans, abruptly resigned as president of Avery College in 1863 with a plan to teach at Liberia College.

He went to Liberia, as he often said, to be a man, which he felt he could not be in the United States, Dr. Hart said. It was an act of self-determination, he said.

But unlike Mr. Freeman, many of the Black Americans who went to Liberia were biracial, the sons and daughters of former enslavers, Dr. Hart said. Being dark complexioned, Mr. Freeman felt discrimination there, too, according to Dr. Hart.

Mr. Freeman taught at Liberia College and subsequently became its president. He died in Monrovia, Liberia, in 1889.

“I think that what is important for Vermonters to know is that there has always been a place for persons of African descent in the state of Vermont,” said Curtiss Reed, executive director of the Vermont Partnership for Fairness & Diversity. He would like to see more public works of art like the sculpture of Mr. Freeman.

“There are those who would say that we can deny the existence of folks of color as well as their contributions, whether as pastors, or as legislators, or as business people, as abolitionists, as veterans,” he said. “There’s a lot of education to be done.”