In context

Protesters and politicians alike are redefining Richmond by removing racist and obsolete symbols of oppression and inequality from public spaces

Brian Palmer | 6/11/2020, 6 p.m.

Editor’s note: The statue of Confederate President Jefferson Davis was toppled from its stand at Monument and Davis avenues about 11 p.m. Wednesday after Free Press deadline. Police watched, and a crowd cheered, as a tow truck hauled it away. The statue was erected on the site in 1907.

The daily explosion of young activists on Richmond streets is forcing a reckoning with Virginia’s racist past and the symbols of oppression that hang over it.

With their voices — and their feet and hands — demonstrators have seized control of the stalled conversation about police brutality from politicians and pundits, their myth-busting starting almost immediately after the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis by a white police officer.

Confederate monuments became targets of rage by people who see them as symbols of systemic racism, which allows lethal police violence and abuse of black people to go unchecked.

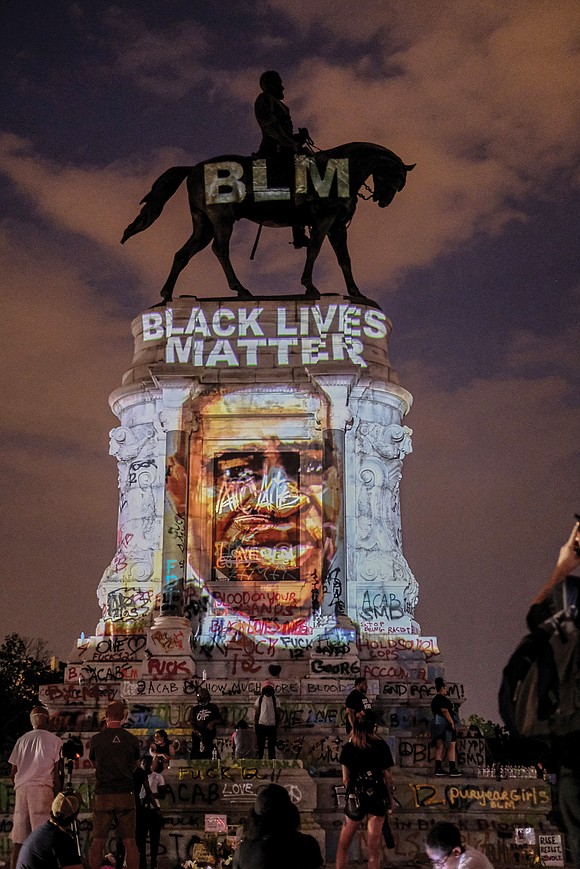

Even as Gov. Ralph S. Northam announced last week that the 21-foot-tall, 12-ton bronze statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee would be removed from Monument Avenue, graffitists already had covered its base — as well as the statues of Confederates J.E.B. Stuart, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and Confederate president Jefferson Davis on Monument Avenue with hundreds of colorful tags such as “Black Lives Matter” and profanity aimed at the police.

On Saturday night, protesters knocked down the statue of Williams Carter Wickham, a Confederate general and enslaver, in Monroe Park. By Sunday morning, that statue was gone, reportedly taken by the National Guard for safekeeping.

And late Tuesday night, activists wrenched Byrd Park’s bronze statue of Christopher Columbus from its base and dumped it in Fountain Lake. On Wednesday morning, city workers hauled it away like a corpse.

Textbook history portrays Columbus as the “discoverer” of the New World, ignoring his genocidal acts against the indigenous Taino people he “discovered.”

Elected officials are playing catch-up, but even they are starting to recognize the handwriting on the pedestal.

The Lee statue, said the governor, represents a “system that was based on the buying and selling of enslaved people” and “false version of history, one that pretends the Civil War was about state rights and not the evils of slavery. No one believes that any longer.” And so in the governor’s words, “we’re taking it down.”

In a statement to the Free Press, Lt. Gov. Justin E. Fairfax called the events of last 10 days “inspiring,” but said there’s more to do.

“We must focus on tearing down other monuments to systematic racism,” he said. “Those include rebuilding crumbling schools, changing a justice system that has always been racially biased against African-Americans and continuing to build a health care system that serves all equitably.

“The Confederate monuments must come down,” he continued. “But the monuments to bias and racism that have endured for decades must also be replaced with hard policy that results in systemic change.”

Supporting Gov. Northam’s stance at his June 4 announcement were more than a dozen people, among them Lt. Gov. Fairfax and other descendants of enslaved people; the Rev. Robert W. Lee IV, the great-great-grandnephew of the Confederate commander; state Attorney General Mark R. Herring; and Robert Johns, brother of the late Barbara Johns who, in 1951, led a student walk-out to protest inferior educational facilities in segregated Prince Edward County. Her efforts sparked a lawsuit that became part of the landmark 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education striking down separate and unequal public schools.

On Monday morning, state employees, contractors, and others in neon vests buzzed around the monument’s heavily graffitied — some would say contextualized — base, while a trio of men inspected the sculpture from a cherry picker as part of the effort to draw up a removal plan.

But just a few hours later on Monday, Richmond Circuit Court Judge Bradley B. Cavedo issued a 10-day injunction halting the removal. A complaint filed with the court by William C. Gregory, a descendant of people who in the late 1800s donated the land for the statue, asserts “that there is the likelihood of irreparable harm to the statue if removed.” This would be in violation of the Commonwealth’s legal obligation to protect the statue made in 1890, Mr. Gregory’s complaint asserts.

The Monument Avenue Preservation Group, a loosely organized group of Monument Avenue residents and others dedicated to preserving the street and sculptures, stated on Facebook that it supports the injunction.

But the governor reiterated his plan to take the statue down, noting in a statement to the Free Press and at a media briefing on Tuesday that the administration is on “very legal, solid ground” and anticipated a court challenge to a removal plan that has been in the works for at least a year.

While the administration is reviewing the order, “Gov. Northam remains committed to removing this divisive symbol from Virginia’s capital city, and we’re confident in his authority to do so,” his office said in a statement to the Free Press.

During the weekend, members of Richmond City Council unanimously said they will back a plan announced by Mayor Levar M. Stoney and Councilman Michael J. Jones to remove the other four Confederate statues on Monument Avenue that are under city control.

This response by city and state leaders — along with the hands-on approach by some protesters — goes far beyond what Mayor Stoney’s Monument Avenue Commission called for in

its 2018 final report, which recommended removal only of the Jefferson Davis statue and for contextual signs to be erected around the others.

The reaction from less radical quarters has been more traditional, but just as clear.

“The Virginia State Conference (of the NAAP) stands with Gov. Northam,” Robert N. Barnette Jr., president of the statewide branch of the civil rights organization, said in a statement released last Friday.

“White supremacy is personified in these Confederate monuments. And while Klansmen, neo-Nazis and white nationalists defend them as an innocent representation of a mythologized ‘American Heritage,’ we know that these symbols glorify treason and a hateful history of black subjugation, reinforced through domestic terrorism.

“In order for our Commonwealth to move forward — to become a state united and free from inequity and bigotry — we must remove, not protect, Confederate symbols from the parks, schools, streets, counties and military bases that define America’s landscape and culture. These monuments are not history and (their) continued presence in this country is a signal to people of color that America has not repudiated racism.”

Meanwhile, state Republicans had a different take on the governor’s announcement.

The state Senate Republican Caucus expressed its “outrage” at Mr. Floyd’s killing, but said the removal of the Lee statue “was not in the best interests of Virginia.” They added: “Attempts to eradicate instead of contextualizing history invariably fail.”

The caucus also questioned Gov. Northam’s motives and took a swipe at one of their own, GOP Sen. Amanda Chase of Chesterfield, a far right candidate for governor, for her “idiotic, inappropriate and inflammatory response” calling the governor’s action a “cowardly capitulation to looters and domestic terrorists.”