Richmond Police detectives indicted on misdemeanor charges

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 10/8/2020, 6 p.m.

The Richmond Police Department appears to have largely dodged a legal bullet from the actions of its officers during the spate of protests over police brutality and racial injustice during late spring.

Capping at least a 90-day investigation, Richmond Commonwealth’s Attorney Colette W. McEachin on Monday presented 18 charges against eight officers to a Richmond grand jury.

But the grand jury sent back only two indictments against two Richmond officers for misdemeanor assault and battery — charges considered relatively minor, although conviction carries the potential for up to a year of jail time and a fine and would open the door for possibly expensive civil lawsuits.

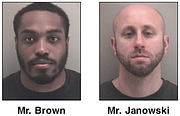

The two officers who were indicted are Detective Christopher Brown, 28, who has been on the Richmond police force for five years, and Detective Mark Janowski, 34, who has been on the force for six years.

Because the charges presented to the grand jury were sealed, and state law requires grand jury proceedings to be secret, nothing is known about the six other officers and why charges were sought against them.

Detectives Brown and Janowski were processed Monday night and released on their own recognizance. They both appeared in Richmond Circuit Court on Wednesday, but the setting of a trial date was postponed until early November to allow them to confer with their attorneys to decide whether to have a jury trial or have a judge decide their guilt or innocence.

Both have been placed on administrative duties.

“These events are unfortunate,” Richmond Police Chief Gerald M. Smith said in a statement. “However, we must allow the legal process to work. The officers will be placed on administrative assignment until a verdict is reached.”

He declined further comment.

For now, all that is known is that something happened involving the two men around 5:24 a.m. Sunday, May 31, in the 200 block of West Grace Street outside Richmond Police Headquarters, at the end of a rampage by protesters in which windows along Broad Street were broken and buildings were set ablaze and looted.

No other details are available on the specific incident, including whether there is any connection between the detectives’ arrests and two civil lawsuits from bystanders alleging that police officers pepper-sprayed them without cause on May 31.

A defense attorney noted in court on Wednesday that there is video of the event. That video is likely to play a major role in the case, depending on its quality.

What is known is that both detectives were part of a large contingent of police from Richmond and at least four other law enforcement agencies who were engaged for hours trying to control the sudden protests and riots that erupted after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25.

Protests broke out in cities across the country and the globe, with the first of a wave occurring in Richmond on Friday, May 29. Richmond protests began peacefully during the day and turned violent at night, mostly in the first few days.

On Saturday, May 30, protesters marched through Richmond and converged on Richmond Police Headquarters, resulting in a chaotic and raucous demonstration. Officers ultimately fired tear gas at least twice in a bid to disperse the crowd that some believed were trying to take over police headquarters.

According to reports, protesters lighted and threw firecrackers and pelted officers with bottles and other objects. Dumpsters were set on fire near the headquarters.

After the tear gas was fired, the protesters scattered, breaking into large, virtually uncontrollable groups. Through the early hours of Sunday, the protesters sought to burn down an apartment building at 309 W. Broad St., as well as the headquarters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy on Arthur Ashe Boulevard.

Windows were smashed along Broad Street, the Rite Aid drug store at Belvidere and Broad streets was torched, as were a group of retail stores located further west at Bowe Street. The damage went on past the Boulevard, where a state liquor store and another drug store had windows smashed.

The damage led Gov. Ralph S. Northam to declare a state of emergency to authorize a short-lived curfew and became a key document in enabling Mayor Levar M. Stoney, a month later, to order the removal of the city’s Confederate statues.