Black Music: Often Appropriated Can’t Be Duplicated

Yesha Callahan | 1/8/2014, 5:04 p.m.

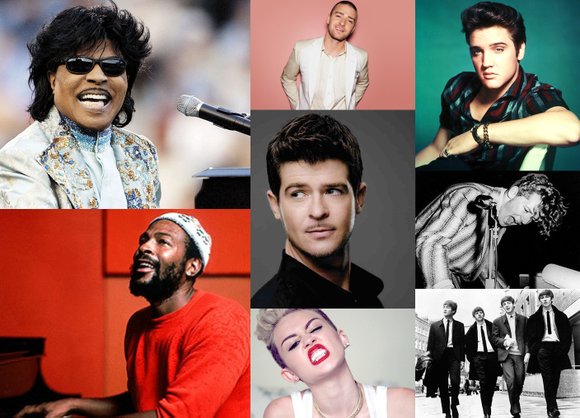

2013 could be considered the year where black music was not only heavily appropriated, but also appropriated to the point of no return. Miley Cyrus proved to be the Queen of Appropriation when she shocked the world with her gold grills and twerking, or what she thought was twerking, in the video for her song, “We Can’t Stop”. From there we entered the world of Justin Timberlake, fresh off a musical hiatus, along with Robin Thicke, both of whom have been dubbed the new “blue eyed soul”.

But Cyrus, Thicke and Timberlake aren’t doing anything new. In the words of Paul Mooney, "Everybody wants to be a n word, but nobody wants to be a n word”.

Appropriation in music and pop culture started way before any of these stars were even born, or probably their parents.

The music from the 1940s and 1950s that was done by African Americans, has basically laid the ground work for today’s music. Before Rock and Roll, there was the delta blues sound that eventually was called rhythm and blues. Some of the biggest appropriators of black music back in the day were Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, The Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin.

The unfortunate facts that remain, is that although most of these artists, besides Jerry Lee Lewis, made a fortune off the sounds of blackness, the originators rarely saw a cent. In order for record labels to make money and market R&B to white audiences, companies used a practice called “mainlining”. Record labels hired white artists to take songs that were performed by black artists and “clean them up”. The lyrics were rewritten to make them suitable for radio and the instrumentals were reworked. This mixing of rhythm and blues from black people and country music from white people was eventually known as rock ‘n’ roll.

One of the first big hits from mainlining was “Shake, Rattle and Roll”. In 1954, Jesse Stone wrote the song under his alias Charles E. Calhoun, and it was then sung by “Big” Joe Turner. Although Turner’s song hit the rhythm and blues charts back in June 1954, it wasn’t until the following month when the Comets recorded their version and released it in August. That version was on the top 40 charts for twenty-seven weeks. No one heard a peep from Turner’s version again.

Whether it’s mainlining or appropriation, regardless of the decade, there’s no mistaking that black music and our culture is something to be in awe of.

One of 2013’s biggest R&B hits came from Robin Thicke and his song “Blurred Lines”. At first listen, many people might have thought the music sounded familiar, but music aficionados quickly recognized a sample from Marvin Gaye’s “Got To Give It Up” and Funkadelic’s “Sexy Ways” in the song. Instead of fessing up to using the samples, Robin Thicke, T.I and Pharrell Williams filed a lawsuit against Gaye’s estate, before they had a chance to file one against them. The lawsuit claimed that there were no similarities between Blurred Lines and the other songs “other than commonplace musical elements.” The trio sought a declaration that the “Gayes do not have an interest in the copyright to the composition ‘Got To Give It Up’ sufficient to confer standing on them to pursue claims of infringement of that composition.”

The Gaye family followed up with a countersuit against Thicke, alleging that he not only infringed upon “Got to Give it Up,” but also committed copyright infringement on “After the Dance,” for the title track from his 2011 album, Love After War. The siblings claimed that Thicke practically admitted to copying “Got to Give it Up” in interviews with GQ and Billboard. In interviews with the publications, Thicke admitted to getting “inspiration” from Marvin Gaye.

Although many present day artists get “inspiration” from black artists from the past, the thin line of appropriating and appreciation is something that has been repeatedly crossed.