From slave to legislator

Virginia’s early black lawmakers honored

Joey Matthews | 7/9/2015, 11:49 a.m.

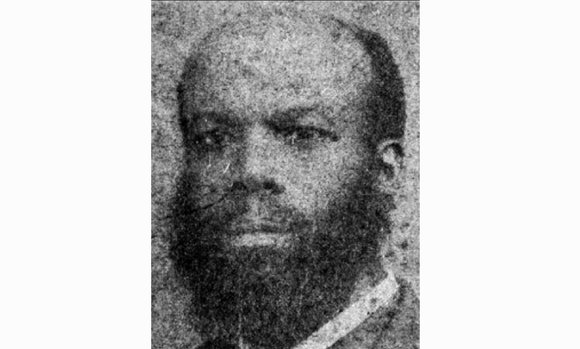

James Apostle Fields started life in Virginia as a slave in Hanover County.

By his death in 1903, he had gone to Hampton University, earned a law degree at Howard University and been elected to the Virginia House of Delegates.

From 1889 to 1890, he represented James City, Williamsburg, Warwick (now Newport News) and York counties and Elizabeth City in the General Assembly.

His great-great-granddaughter, Ajena Rogers, was among about 200 descendents of Mr. Fields and other trailblazing African-Americans who served in the General Assembly from 1867 though Reconstruction that attended a “Family Reunion” Monday at the State Capitol to honor their descendants’ legacy.

At the reunion, they took the Slave Trail Walk, toured the State Capitol, viewed the “Remaking Virginia: Transformation through Emancipation” exhibit at the Library of Virginia, and enjoyed a private reception and a public forum to discuss their descendants’ legacy.

The group hailed from as far away as California and Arizona to New York, South Carolina and Virginia and ranged in age from 2 to 92. The descendants were buoyed by the recognition of their ancestors and the legacy they left.

“That legacy has come down through all generations of my family,” Ms. Rogers said. “All of us, except one, have worked in some form of civil service.”

Robert Lipscomb of Cumberland County said he came to honor his descendant, James F. Lipscomb, who represented Cumberland County from 1869 to 1877 in the General Assembly.

“It’s an honor and it’s a privilege to know he was one of the forefathers, someone who cared about his country and took his time to see that his country was put on the right path,” he said.

Milton Brown of Richmond paid tribute to his great-grandfather, Goodman Brown, who served in the House of Delegates from 1887 to 1888.

“I’m very proud to say that, during those times, there were courageous people like him who stepped up to serve,” he said.

State records show that African-Americans served as early as the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867-1868. They were elected to the constitutional convention that was required by Congress after the Civil War as a condition of Virginia’s re-admission into the Union. It required the state to create a reconstructed government and establish a new constitution.

Known as the Underwood Convention for federal Judge John Underwood who served as the convention’s president, it created a new Virginia Constitution ratified in 1869 that gave all men, including African-American men, the right to vote. Women did not get the right to vote until 1919.

As a result of the new Constitution, about 100 African-American men served in the Virginia Assembly between 1869 and 1890.

Panelists at the forum were Ms. Rogers, a historian and supervisor ranger with the National Park Service at the Maggie Walker National Historic Site; Viola O. Baskerville, a former member of the Virginia House of Delegates and former state secretary of administration; Hampton Sen. Mamie E. Locke, chair of the Virginia Legislative Black Caucus; and Juanita Owens Wyatt, a member of the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Commission and also a descendant of Mr. Lipscomb and Peter G. Morgan of Petersburg, who served in the Underwood Convention and in the House of Delegates from 1869 to 1871.

The event was co-sponsored by the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Commission, the Library of Virginia, the Virginia House of Delegates and the Senate of Virginia.

Richmond Delegate Jennifer L. McClellan, who chairs the King Commission, delivered opening remarks and called the event an opportunity “to fill out more of Virginia’s full history.”

“They paved the way for those of us who came later,” she added.

Ms. Baskerville outlined the history of the early African-American legislators and the hard-fought battle for civil rights that followed. She said she had sought to have their story told since her first year in the General Assembly in 1998.

She called it “a labor of love and inquiry.”

She said they “had to have been very courageous men” to endure what they did at the time.

Sen. Locke said racism today is more of “a quiet bias,” but it still exists.

“We may no longer have Jim Crow, but he’s now James Crow, Esquire,” she said.

She cited the “assault on unarmed black boys and men,” including Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown Jr. and Eric Garner, and the disparities against African-Americans in the criminal justice system.

She assailed the Confederate flag and what it represents. “It’s about not wanting African-Americans to have equal rights or to desegregate the South,” she said.

“We’re faced with a ‘Massive Resistance,’” she added, citing legislative efforts to stymie voting rights, resistance to President Obama’s policies and the U.S. Supreme Court decision that struck down part of the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965.