Anguish of a nation

From memorial services to protests, numerous questions arise after senseless killings

Free Press staff, wire reports | 7/15/2016, 7:17 a.m.

“Can we all get along? Can we get along? Can we stop making it, making it horrible …?”

The late Rodney King spoke those memorable words as he called for calm in 1992 after the acquittal of four white police officers who were videotaped savagely beating him triggered riots in Los Angeles.

His questions still hang over a nation reeling from more horrific violence involving police and African-Americans, like a terrible movie in which the story line remains the same and only the participants change.

This time, the uproar was triggered last week by police shootings of African-American men in Louisiana and Minnesota, the graphic images from which were spread through social media. The violence then was capped last Thursday evening by an embittered African-American war veteran’s stunning ambush of police in Dallas that left five law enforcement officers dead and seven other officers and two civilians wounded.

Nearly two years after the slaying of teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., turned the spotlight on police killings and mistreatment of African-Americans, the wrenching debate over race and criminal justice seems as intense as ever.

On Tuesday, President Obama used a memorial service in Dallas for the slain officers to appeal to Americans to do more to overcome the racial divisions and mutual suspicions that undermine police-community relations.

But the president seemed uncertain whether he and the country are up to the task.

“I am not naive. I have spoken at too many memorials during the course of this presidency,” he said in a reflective address at the Dallas service. “I have seen how inadequate my own words have been.

“Can we find the character, as Americans, to open our hearts to each other? Can we see in each other a common humanity and a shared dignity, and recognize how our different experiences have shaped us?” President Obama asked.

“I don’t know. I confess that sometimes I, too, experience doubt.”

The task of finding a calm center that emphasizes shared values and the important work of racial reconciliation has become all the more difficult in a bitter and polarized presidential election season.

President Obama praised police officers for doing difficult and dangerous work, even as he called attention to broader problems with policing practices in many communities.

Even as he consoled the mourners, he also addressed what he sees as the problem: “If we’re honest, perhaps we’ve heard prejudice in our own heads and felt it in our own hearts,” and that needs to be acknowledged and addressed.

“None of us is entirely innocent,” he said of the bias and discrimination that still afflicts the nation. “No institution is entirely immune, and that includes our police departments.”

Even in Richmond, the police relationship with residents remains a work in progress, although complaints about police use of excessive force reportedly have dropped to a low — along with crime — as a recent succession of police chiefs and officers have made strengthening community ties a priority.

One indication came Tuesday evening after a community conversation led by Richmond Mayor Dwight C. Jones and city Police Chief Alfred Durham at Martin Luther King Middle School. Even as area residents were given space to vent their concerns, that did not stop vandalism of the city’s memorial statue to fallen police officers in Byrd Park that was found Wednesday marred with red spray paint.

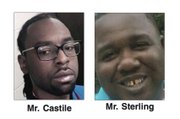

The events that gripped national attention were spread over three days of bloodshed, all made more vivid by streaming video on Facebook. The troubles began early Tuesday, July 5, with the graphic images of two Baton Rouge, La., police officers grabbing Alton B. Sterling and one of them shooting him at point-blank range after both apparently had pinned him to the ground. Baton Rouge police quickly turned the investigation over to the U.S. Justice Department and the FBI.

The spray painters who marred the police memorial in Richmond included the message, “Justice for Alton” on the stones in front of the statue.

Then, during the evening of Wednesday, July 6, more than 1,000 miles away in Falcon Heights, Minn., outside St. Paul, a police officer opened fire during a traffic stop and killed Philandro Castile, 32, as he apparently reached for his ID. He was in the car with his girlfriend and her 4-year-old daughter at the time. His girlfriend had the presence of mind to turn on her cell phone video and streamed to the nation her boyfriend’s death and her remarks to the officer.

The shootings in Louisiana and Minnesota follow a long string of deaths of African-Americans at the hands of the police — in Staten Island; Cleveland; Baltimore; and North Charleston, S.C., among others — that have kept outrage on boil, particularly after most officers involved were cleared of wrongdoing.

The situation turned upside down after night fell on Thursday, July 7, with the shootings in Dallas, as police officers provided protection and security for people peacefully, but loudly demonstrating against the killings of Mr. Sterling and Mr. Castile.

The shooting of police generated an outpouring of support for officers and made little sense to most people in Dallas, given the efforts of the department to overcome a reputation for brutality. Even President Obama noted the Dallas department “is doing it the right way.”

Since taking over in 2010, the current police chief, David O. Brown, has overhauled policies, pushed community policing and improved training for officers. He has secured body cameras and improved accountability. During his tenure, complaints of excessive force have fallen by 83 percent as a result of the changes he has made.

None of that seemed to impress the embittered, heavily armed shooter, Micah Xavier Johnson, 25, who authorities said was a devotee of the New Black Panther Party. He was later cornered and then killed with a bomb delivered by a robot when he refused to surrender. Chief Brown said that Mr. Johnson went on the spree “to kill white police officers” apparently in payback for the killings in Louisiana and Minnesota.

Aboard Air Force One en route to Texas, President Obama called family members of Mr. Sterling and Mr. Castile to offer his condolences and those of First Lady Michele Obama.

Former President George W. Bush, who lives in Dallas, also addressed the mourners at the service for the five officers and sought to project a common purpose beyond politics.

“Too often we judge other groups by their worst examples, while judging ourselves by our best intentions,” Mr. Bush said in urging more work on race relations.

During his tenure, President Obama has spoken at more than a dozen memorial services, most of which involved mass killings by an armed perpetrator determined to wreak havoc.

In June, he and Vice President Joe Biden traveled to Orlando, to console families and meet survivors of a tragic massacre at a gay nightclub.

And just a year ago, President Obama stood before another packed house of mourners in Charleston, S.C., to remember nine black parishioners killed by a white gunman during Bible study.

In Charleston, President Obama expressed hope that the killings at Emanuel A.M.E. Church could be a turning point for the nation to address some of its most entrenched problems — guns, racial discrimination and poverty.

Since then, there have been more mass shootings, including in Roseburg, Ore., and San Bernardino, Calif.

But he has found it frustratingly difficult to advance gun control legislation or secure criminal justice reform that he sees as essential to ending the bloodshed.

Meanwhile, racial tensions also seem to have increased on his watch as the first African-American president, with police shootings adding to the anxiety.

During his address in Dallas, President Obama called on police and their supporters not to ignore the complaints of protesters who point to racial disparities in encounters with police, including searches, arrests, shootings and sentencing as evidence of continuing bias.

“To have your experience denied like that, dismissed by those in authority, dismissed perhaps even by your white friends … it hurts,” President Obama said. “Surely we can see that, all of us.”

At the same time, he said that protesters and civil rights activists must show more understanding of the plight of police officers, who are often assigned to patrol dangerous and forgotten neighborhoods without sufficient resources.

“We flood communities with so many guns that it is easier for a teenager to buy a Glock than get his hands on a computer or even a book,” President Obama said. “We tell them to keep those neighborhoods in check at all costs and do so without causing any political blowback or inconvenience. … These things we know to be true.”

If Americans cannot speak “honestly and openly,” President Obama warned, the problems will fester, and “we will never break this dangerous cycle.”

Still, he rejected the notion that the country was overly polarized. “As tough, as hard, as depressing as the loss of life was (last week), we’ve got a foundation to build on.”

“It’s hard not to think sometimes that the center won’t hold and that things might get worse,” President Obama said. “I understand how Americans are feeling. … we must reject such despair. In the end, it’s not about finding policies that work, it’s about forging consensus and fighting cynicism and finding the will to make change.”

In Richmond, Chief Durham made it clear that Richmond Police has gotten the message and pointed out that the department developed 22 programs to mentor kids.

“We’re all about the business of the preservation of life,” he said at Tuesday’s meeting. “It’s as simple as that,” he continued in citing the department’s priorities: “Building relationships, preserving life and making the community strong to drive our crime down.”