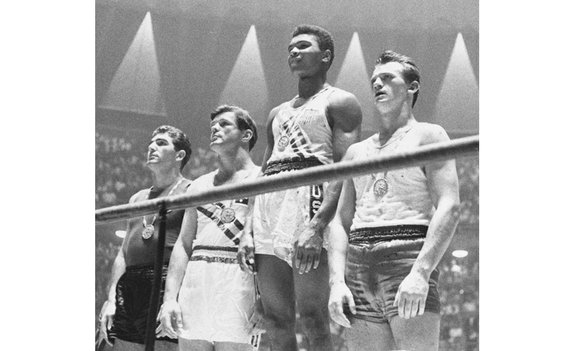

Ali was golden starting in 1960 Olympics

Fred Jeter | 6/10/2016, 6:51 a.m.

The 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome were held during the height of the bitter Cold War.

Helping to ease world tension was 18-year-old Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., just two months after his graduation from Central High School in Louisville, Ky., where he was a bit of a class clown.

Clay’s playful antics included racing the school bus down neighborhood streets, losing ground when the bus was moving and then gaining the lead — to the delight of the student passengers — when the bus stopped for pick ups.

Running was central to his boxing regimen.

Clay reportedly was introduced to the sport after his bicycle was stolen at age 12. While reporting the theft to police, young Clay vowed to “whip” whoever stole it. The officer, Joe Martin, told him he had to learn how to box first and invited Clay to the local Police Athletic Club.

Quickly, Clay became the Kentucky Golden Gloves champ, a title he won six times, along with the national Golden Gloves title, which he won twice.

He carried his Hollywood smile and his jaw-dropping athleticism across the Atlantic Ocean to the Olympics in August 1960.

Once in Rome, Clay, who later would change his name to Muhammad Ali, was so intent on shaking everyone’s hand he was dubbed the “mayor of the Olympic Village.”

The outgoing teen became particularly chummy with U.S. sprinter Wilma Rudolph, the long-legged, 20-year-old from Tennessee State University who won three gold medals in the competition. The two were frequently photographed together and became life-long friends.

Young Clay, competing in Olympic boxing’s light heavyweight class, warmed hearts with his smile and broke opponent’s dreams with a quick-fisted, quick-footed boxing style that later would be dubbed the “Ali shuffle.”

In claiming the gold medal before capacity crowd of more than 16,000 at Palazzo dello Sport, Clay won four bouts, all against Europeans. He defeated Belgium’s Yvon Becaus by technical knockout, and then Gennadiy Shatkov of the Soviet Union, Australia’s Anthony Madigan and, finally, Poland’s three-time European champ, Zbigniew Pietrzykowski.

Clay won the quarterfinal, semifinal and final matches all by 5-0 unanimous decisions.

Winning in the ring was the easy part. After all, Clay was 100-5 as an amateur and was the lone American to score a knockout at the U.S. Olympic Trials finals earlier in California.

However, getting to Rome posed a problem. Clay endured bouncy flights to and from the U.S. Olympic Trials and developed a flying paranoia. He vowed not to board a jet to Rome, and instead requested to travel by ship.

When he learned he couldn’t sail to Europe, he agreed to fly — but only with a parachute strapped on his back during the entire trip.

Clay wasn’t alone in the Italian Olympic spotlight.

Two other U.S. gold medalists in boxing were African-American. Wilbert McClure won the light middleweight division and Eddie Crook struck gold in the junior middleweight division.

Also during the Rome Olympics in 1960, Rafer Johnson, who would become famous as a bodyguard for Robert F. Kennedy, won the decathlon.

And Ethiopian Abebe Bikila became the first sub-Sahara African to earn Olympic gold by finishing first in the marathon. Astonishingly, Bikila ran the 26.2 miles barefoot.

Clay wasn’t the first U.S. Olympic champ to become the world’s heavyweight champion. Floyd Patterson used his Olympic win in 1952 in Helsinki, Finland, to launch his illustrious pro career.

George Foreman, who would lose to Ali in the 1974 “Rumble in the Jungle” in Zaire, won the Olympic heavyweight title in 1968 in Mexico City.

Just two months after the 1960 Olympic Games, Clay turned pro and began an ascent to the world heavyweight throne.

He became famous for his fast fists, fancy feet and rhyme-laced predictions of upcoming bouts. Before challenging champion Sonny Liston in 1963, Clay got poetic with reporters:

“He’s big and tough and his name is Clay,

He calls the round and puts ‘em away;

The hide he wants is Sonny Liston’s,

To win, his fists must work like pistons.”

He would go on to become known as heavyweight champion of the world, Associated Press athlete of the century, the greatest of all time, cultural icon, philanthropist and beloved senior citizen.