Smithsonian’s Quran exhibit aims to dazzle, while offering opportunity for understanding

11/4/2016, 6:40 p.m.

By Lauren Markoe

Religion News Service

Islam prohibits the depiction of God or prophets, and some Muslims believe drawing any animate being is also forbidden. Certainly no such images appear in the Quran, its central holy book.

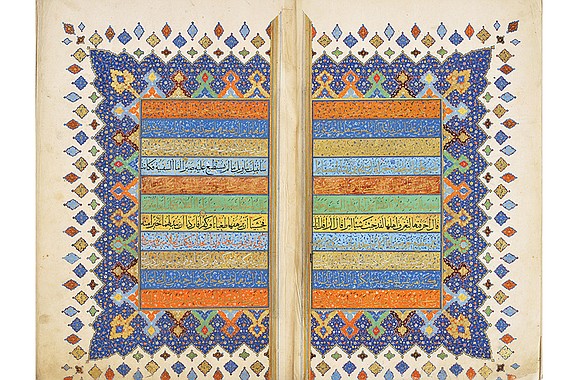

So there are no pictures per se in “The Art of the Qur’an,” the first major exhibit of Qurans in the United States. It is on display at the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery on the National Mall until Feb. 20. What visitors to the exhibit can expect to see is words, thousands of Arabic words.

But these words, within the more than 60 Qurans on display, present a visually stunning tour of more than 1,000 years of Islamic history, told through the calligraphy and ornamentation that grace the sacred folios.

“We can convey a sense of how artists from North Africa to Afghanistan found different ways to honor the same text, the sacred text of Islam,” said Sackler Gallery director Julian Raby.

“They found different forms of illumination and binding to beautify the manuscripts they had copied. But above all, they developed different forms of script to express in a dazzling array of calligraphic variety the very same text. The results could be intimate, or they could be imposing. But in every case, the scribe invested his calligraphy with piety.”

The Qurans in the exhibit come almost exclusively from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts in Istanbul. Intricate calligraphy and rich ornamentation made these Qurans cherished possessions of some of the most powerful people of the Muslim world. Each comes with a rich story of those who commissioned it, copied it, entombed it or preserved it. Many were offered as gifts to forge military and political alliances.

Essentially though, Qurans are religious objects, the word of God that Muslims believe was transmitted through the Angel Gabriel to the Prophet Muhammad in the 7th century, when Islam was founded. Details within the text and on the margins of the parchment convey the pronunciation of words and the cadence of the verses.

Intricate ornamentation — geometric illuminations in gold, azure and other brilliant colors — beautify the pages, but also serve a function, said Simon Rettig, assistant curator of Islamic art at the Sackler Gallery.

“They help the readers locate themselves within the Quranic text. They tell you when you have to prostrate yourself,” he said, pointing to a complex geometric emblem in an early 14th century manuscript by Abdallah al-Sayrafi, a master calligrapher who worked in Tabriz, a historical capital of Iran.

Mr. Al-Sayrafi was trained in six Arabic scripts, and uses three — sometimes writing in gold, sometimes in black — in one of Mr. Rettig’s favorite Qurans in the exhibit. His illuminations look like multicolored sunbursts and gilded foliage blossoms.

The exhibit, on two floors of the Sackler Gallery, also aims to explain the Quran as scripture meant to be heard. Written down shortly after the founding of Islam, the Quran is verses to chant.

“Calligraphy is a way to capture the beauty of the orality,” said Dr. Massumeh Farhad, chief curator at the Sackler and Freer galleries, which form the Smithsonian’s Asian art collections and exhibits.

Scholars don’t know exactly how scribes wrote Qurans centuries ago. Dr. Farhad said it is possible they would inscribe verses as they were recited, each showing reverence through his skill and style.

“That’s why the work of Yaqut is considered so supreme,” Dr. Farhad added, referring to the 13th century master scribe who worked in Baghdad for the last caliph of the Abbasid dynasty. “It has this sort of lightness. It seems to float on the page.”

The exhibit is not intended as commentary on today’s politics, its organizers said. Work started on the project six years ago, before sharp rises in Islamophobic rhetoric and violence in the United States and Europe, and before Muslim immigration and culture became a flashpoint in American and European politics.

But the Smithsonian is not sorry for the timing, and hopes the exhibit can help quell fears of Islam and its followers.

“The Art of the Qur’an” comes at “a difficult moment” in world affairs, said Mr. Raby, who said it may lead some to “reflect on their own assumptions.”

As the exhibit makes clear, Muslims refer to Jews and Christians as “ahl al-kitab” — people of the book. The curators show how the Quran, the Torah and the Christian Bible share variations of the same stories, and the same prophets’ teachings. One Quran at the Sackler Gallery is turned to a sura, or chapter, that explains:

“Step by step, He has sent the Scripture down to you [Prophet] with the Truth, confirming what went before: He sent down the Torah and the Gospel earlier as a guide for people and He has sent down the distinction [between right and wrong].”

The Turkish multinational Koc Holdings is the principal sponsor of “The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts.”