Would domestic terrorism law help prevent extremist shootings?

Free Press wire reports | 11/8/2018, 6 a.m.

WASHINGTON

The package bombs sent to Democrats across the country and the killings of Jews at a Pittsburgh synagogue may seem like clear-cut cases of terrorism. But the suspects will almost certainly never face terrorism charges.

The reason: There’s no domestic terrorism law in the United States.

Whether there should be one is a matter of debate. On one hand, there’s the belief that white supremacists who kill for ideology should get the same terrorism label as Islamic State group supporters. On the other, there’s concern about infringing on constitutional guarantees to protect free speech, no matter how abhorrent.

In the absence of domestic terrorism laws, the U.S. Justice Department relies on other statutes to prosecute ideologically motivated violence by people with no international ties. That makes it hard to track how often extremists driven by religious, racial or anti-government bias commit violence in the United States. It also complicates efforts to develop a universally accepted domestic terror definition.

Mary McCord, a former top Justice Department official in the Obama administration, favors a law that “puts domestic terrorism on the same moral plain as international terrorism.”

“Terrorism offenses are done purposely to send a much broader message, and so having that be the charged crime puts that label on that and says, ‘This is someone who committed a terrorism act,’ ” she said.

The discussion in some ways is more about labels than consequences. Even without a specific law, the Justice Department has other tools available, including explosives, hate crime and firearm possession charges. The penalty can easily be every bit as severe as in the international terrorism cases the Justice Department routinely brings against people who align themselves with foreign extremist groups and carry out violence in their names.

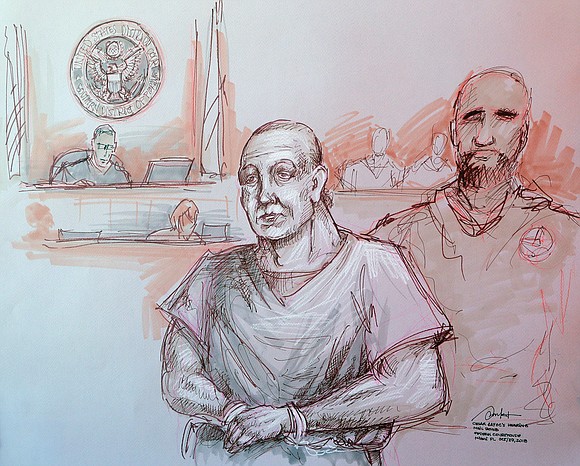

Both Cesar Sayoc, accused of sending more than a dozen explosive packages to high-profile critics of President Trump, and Robert Bowers, accused of killing 11 inside the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, could face decades in prison. In the case of Mr. Bowers, charged in a 29-count complaint with federal crimes including using a firearm to commit murder and obstructing the free exercise of religion, prosecutors intend to seek the death penalty. The same punishment was sought for Dylann Roof in the 2015 shooting at Mother Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, S.C.

Prosecutors are treating the synagogue shooting as a hate crime rather than domestic terrorism. Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein told police officials on Oct. 29 that the Justice Department is aggressively prosecuting hate crimes, saying, “The vile forces of bigotry and hatred will not prevail.”

Opponents of domestic terrorism laws say prosecutors already have enough tools. They worry what would happen if law enforcement were empowered to apply the same tools to a domestic investigation, like a secret warrant to monitor communications, as they have for international investigations. They also contend that increased powers could run afoul of civil liberties protection and lead to groups being classified as terror organizations just because the government didn’t like their ideology.

“You want to be really careful, given the current political context, about who would be put on that list because you don’t want them put on there for purely punitive reasons,” said Karen Greenberg, director of Fordham University Law School’s Center on National Security.

But advocates of a domestic terrorism law say without a specific statute, cases that could all be charged under a single law are instead brought under a hodgepodge of others and sometimes prosecuted as state or local terrorism offenses, making it virtually impossible to identify trends, and tally how many domestic terror acts occur in the United States and how they’re handled by prosecutors.

When an attack occurs, “you have to find the criminal laws that may apply based upon the specific facts that may apply,” said Joshua Zive, outside counsel to the FBI Agents Association.

“When it does that, you’ve then lost the ability to kind of measure those prosecutions from a domestic terrorism standpoint. They’ve been essentially spread to the wind based on what the individual facts might be,” he said.

The Justice Department, acknowledging the homegrown extremism threat, appointed a domestic terrorism counsel in 2015 to coordinate the work of U.S. attorneys. Although ideas for a broader statute have been kicked around, Mr. Zive said he could not recall any “viable” legislative proposal.

The federal code includes a definition of domestic terrorism but has no penalties associated with it. A proposal floated by the FBI association would borrow the language of that definition — the use of violence for political means to intimidate or coerce a government or civilian population — and make it a crime no matter what type of weapon is used.

The Justice Department historically has reserved terrorism prosecutions for cases involving foreign organizations. That’s because the U.S. State Department maintains a list of dozens of foreign terror groups. Actions aimed at helping those organizations, whether traveling abroad to join the Islamic State group or committing an act at home, fall under a broadly construed law that makes it illegal to lend material support to a foreign terror organization.

By comparison, the United States does not make it a crime to associate with organizations like the Ku Klux Klan that have been involved in ideologically motivated crimes.