Songs of redemption

Documentary film captures noted hip-hop artist ‘Speech’ of Arrested Development helping men incarcerated at the Richmond City Justice Center make strides toward better lives through music

By Samantha Willis | 10/18/2018, 6 a.m.

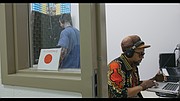

For 10 days, hip-hop artist Todd “Speech” Thomas, the front man for Arrested Development, worked inside the Richmond City Justice Center helping inmates to tell their stories via music.

They sang, rapped and played out their pain in music, part of a method to unearth the past and open new chapters in the lives.

It was all captured on film in a documentary, “16 Bars,” that will premiere locally on Monday, Nov. 4, at the Byrd Theatre in Carytown.

Several years ago, “I was watching a TV show, and saw Sheriff (C.T.) Woody’s work at the jail and the different organizations giving their time and efforts trying to rehabilitate the incarcerated men in positive, healthy ways, and I respected that,” said Mr. Thomas, a Grammy Award-winning artist and activist who has been internationally regarded for his socially conscious lyrics for more than three decades.

That television program, “This Is Life with Lisa Ling,” originally aired on CNN in 2015 and spotlighted innovative rehabilitation programming at the Richmond City Jail, now known as the Richmond City Justice Center.

Want to go?

What: Screening of the documentary “16 Bars,” featuring four participants in the Richmond City Justice Center’s REAL LIFE program who worked with Todd “Speech” Thomas of Arrested Development to write and record music reflecting their lives.

When: 1:30 p.m. Sunday, Nov. 4.

Where: Byrd Theatre, 2908 W. Cary St.

Details: The screening is free and open to the public, but tickets are recommended because seating is limited.

Register: www.eventbee.com/v/…

Mr. Thomas said he felt compelled to get involved. And after about two years of dialogue with administrators at the jail, decided to come to Richmond, spend a week and a half the incarcerated men and record music with them in the jail’s makeshift recording studio.

Mr. Thomas’ team contacted filmmaker Sam Bathrick of the Brooklyn, N.Y.-based Resonant Pictures to take the idea further. Mr. Bathrick and his film crew were responsible for adding sight to the sound Mr. Thomas and the inmates created.

The filming started in April 2017, with the last filming in December 2017, which coincided with the end of Sheriff Woody’s administration. The current sheriff, Dr. Antionette V. Irving, took office in January.

“We were thrilled to work with Speech, of course, but I don’t think we knew exactly what we were going to do,” said Mr. Bathrick, whose film “200 Miles” premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival last year. “Once we started working together though, the creative process just took hold. (The film) piloted itself.”

Four men participating in the jail’s REAL LIFE program appear in “16 Bars.” Their struggles show plainly on the screen: Substance abuse and addiction, criminal actions that landed them behind bars, complicated relationships with their families, to name a few.

In the documentary, the men work to identify and correct negative patterns of behavior and learn to make positive choices to benefit their futures, said Dr. Sarah Scarborough, founder of REAL LIFE, a nonprofit that began in 2013 as a rehabilitation and recidivism reduction program for the incarcerated and former inmates at Richmond City Jail.

“The whole premise of the REAL LIFE program is behavior modification. (We) address the behaviors associated with why the person became incarcerated, why they did what they did, why they continue to do what they do,” Dr. Scarborough said.

Part of that rehabilitation process requires creativity, said Dr. Scarborough, who has worked full time as program director at the jail since 2013.

The jail studio’s recording equipment had been donated by Virginia Commonwealth University a few years prior, she noted, and is used as part of the music education component of the REAL LIFE program.

Mr. Thomas “spent the better part of 10 days in the jail, working with the guys, listening to their stories,” Dr. Scarborough recounted. “He even spent a night in the jail.”

The result was a collection of music composed and performed by the inmates. Mr. Thomas coached and produced as the men sang and rapped their stories or played them on instruments.

It was a transformative experience, said Mr. Thomas, underscoring how he has long been concerned about how America over-corrects criminality in a way that is unhealthy and unjust, especially toward African-Americans.

“There is a disproportionate number of black men in jail and prison,” Mr. Thomas said in a telephone interview from Atlanta, his longtime base.

“My son is 23. He knows four or five people who have done time in prison. At that young age, he knows that many black men — personally — who have been sent away. There’s something very wrong in that, something very broken.”

According to a report issued in January by the U.S. Justice Department’s Bureau of Justice Statistics, roughly 486,900 African-Americans were incarcerated in state and federal prisons at the end of 2016. While African-Americans comprise 12 percent of the U.S. population, they made up 33 percent of the number of sentenced prisoners.

The REAL LIFE program helps current and former inmates at the Richmond jail and others suffering adverse circumstances rebuild their lives and perspectives.

The men’s music-making in the documentary reflects their desire for change, Dr. Scarborough said, and offers viewers a different perspective of the incarcerated and a chance to expand their perspective.

“The film really shows the human side to these men who are behind bars — that they made bad decisions, but that they are real people with real emotions, real talent, who have real families,” she said. “The message goes even deeper than the music.”

Mr. Bathrick said the documentary also sheds light on the many challenges people face when re-entering society after incarceration, and the impact that process has not only on individuals, but their families and communities.

“It’s one thing to be in jail, but when you come back, the world you left is still there,” he said. “The environment that led you to criminal activity is still there.”

The film, he said, shows “coming back to your old life and transforming it into your new life.”

Tennyson “Teddy” Jackson, who appears in the film mere days after his release from jail, echoes that sentiment on screen as he recounts his dark past and bright future.

“I feel guilt; I feel a little shame,” he said. “At the same time, I feel empowered. Because I feel like, if I can change, anybody could.”