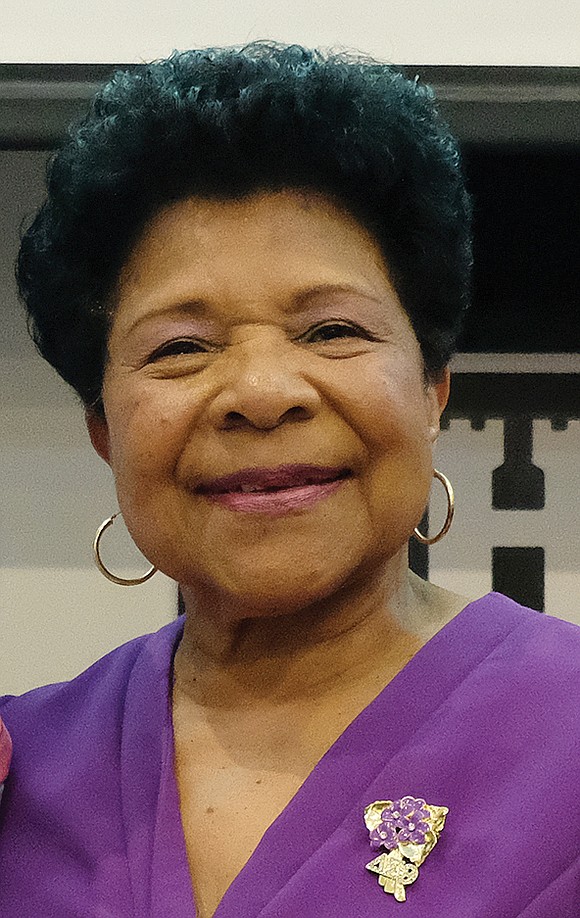

Personality: Dr. Erma L. Freeman

Spotlight on VCU School of Dentistry ‘First 100’ Trailblazer Award winner

7/4/2019, 6 a.m. | Updated on 7/9/2019, 6 a.m.

When she started studying dentistry, Dr. Erma Freeman wanted to be a dentist for fairly simple reasons: good work, good money and time for family.

“I had an interest in the health professions, and I felt dentistry would provide the in- come I desired, the flexibility of work hours I desired and more time to raise children and have a family,” Dr. Freeman says of her decision to enter the Medical College of Virginia School of Dentistry in 1973.

However, fewer restraints and more financial security weren’t why dentistry ultimately proved to be the right choice for her.

Rather, the experience of helping patients in pain, boost- ing their self-esteem by im- proving their appearance and helping them become more informed on their dental needs proved to be far more valuable and fulfilling for Dr. Freeman, a Chase City native.

The benefits of that decision have carried over for decades as Dr. Freeman had a private dental practice in Ettrick for 20 years, was appointed by former Gov. L. Douglas Wilder to the Virginia Board of Dentistry in 1993, worked for 13 years as a dentist with the state Depart- ment of Corrections before retiring and has spent hours in volunteer service, including providing dental exams from the Colgate Van in towns through- out Southside Virginia.

Dr. Freeman was honored with a Trailblazer Award in late April as the Richmond dental school’s first black female graduate as part of the school’s “First 100 Dentists of Color” initiative.

The initiative seeks to pro- vide schoolarships, mentor- ships and fellowship for the next 100 dental students of color at Virginia Commonwealth University, formerly known as MCV.

“I was sailing high, soaring for a while from the honor,” Dr. Freeman says of the ex- perience.

But it was a long road to reach that point.

Dr. Freeman, who had earned her undergraduate and master’s degrees in the late 1960s, was in her fourth year teaching at Linkhorne Jr. High School in Lynchburg when a professor from her graduate school days at Virginia State College alerted her to an op- portunity for minority students at MCV’s dental school. Dr. Freeman reached out, applied, was accepted and started her education in the fall of 1973.

It was not the most welcom- ing place, Dr. Freeman frankly recalls. She spent her four years with a faculty comprised entirely of white men, faced with unfamiliar and unyield- ing learning structures and a lack of minority counselors for guidance.

The more than 400 fellow students in the dental school had fewer than 10 black men and fewer than 10 women, she says.

While she managed to make connections with other students that blossomed into long-term friendships, she also faced racist and sexist rhetoric from school staff members that belittled her intelligence and ambition all the way to the day of her graduation.

“I felt like I was constantly in a jar on display for everyone to see,” Dr. Freeman says.

However, for all the trouble she was put through, Dr. Freeman looks back on her time at VCU with a variety of emotions, describing the time as “challenging, lonely, scary, fast-paced, highly visible and also fun!”

Now volunteering with vari- ous health groups, Dr. Freeman is hopeful more young people of color join the profession.

“The First 100” initiative is helping with that, she notes, adding that VCU has added minorities to its faculty and staff and increased minority participation on the school’s admission committee.

Dr. Freeman recognizes the high bar to admission and the exorbitant cost that come with dentistry education likely have turned off many people of color from pursuing a dental career. But she sees engaging students starting in elementary school, alongside increased scholarship and mentorship programs, as key to creating a more equitable and inclusive field in the profession.

Dr. Freeman hopes her work ensures that dentistry becomes as common an aspiration for the today’s youths as doctors, nurses and other medical professions.

“The more they see people of color — especially women — about in the community, the more younger people know that they can do that as well,” Dr. Freeman says about her volunteer dentistry work.

This comprehensive effort is necessary in Dr. Freeman’s view, given just how important dentistry is in general health care, from infections and disorders that can be gleaned from what is found during dental exams to the connec- tion between gum disease and afflictions ranging from heart attacks to strokes.

Asked why young women of color should want to be- come dentists, Dr. Freeman’s response returns to the reasons that started her own journey down that path: Good work, good money and time for family.

“Dentistry was never in my career plan. It was a shot in the dark that resulted in the most fulfillment and joy I could ever have imagined,” Dr. Freeman says.

“I did not make a fortune, but I was comfortable and have been blessed in many other ways.”

Meet a VCU trailblazer and this week’s Personality, Dr. Erma L. Freeman:

Occupation: Retired dentist.

Latest award: VCU School of Dentistry “First 100 Dentists of Color” Trailblazer Award.

Date and place of birth: Jan. 30 in Chase City in Mecklenburg County.

Current residence: South Hill.

Alma maters: Bachelor’s, Saint Paul’s College in Law- renceville, 1968; master’s in biology, Virginia State College, 1969; and doctor of dental surgery degree, Medical College of Virginia, 1977.

Family: Divorced with one son, W. Warren Hubbard, 37.

My experience at the school as the first African-American female was: Challenging, lonely, scary, fast-paced, highly visible and also fun! Additionally, I had to develop a thick skin.

Years I attended dental school: 1973-1977.

Acceptance at school: I felt I was constantly in a glass jar on display for everyone to see. I made friends in my lab, where we were assigned alphabetically and remained four years, as well as with some other students who had come to dental school from various careers and not straight from college. Some long-term friendships developed from that group. There were others, however, such as a faculty member from the academic campus, who told me I would never get through dental school because I couldn’t read. On my graduation day, a dental school faculty member came up to congratulate me and said that of all the people in my dental school class, I was the one he least expected to graduate. There was an expectation from some that I would fail, but there was encouragement from others.

Why young women of color should consider dentistry: Because it continues to offer many more practice options, more scheduling flexibility than many other professions and the potential for lucrative incomes.

Why so many do not: Dental school may be too cost prohibitive at this particular time. Also, the entrance requirements are very high and the competition for available slots is tremendous.

What can be done to change that: Begin the recruitment process in elementary schools by increasing dental career information, mentorship programs similar to the one currently established locally by the Peter B. Ramsey Dental Society and increased participation in scholarships to help defray the high costs of dental education.

What VCU Dental School is doing to increase diversity: VCU has increased minority faculty and staff and also has increased minority participation on the school’s admission committee that screens and selects applicants. “The First 100” initiative at the school has increased minority involvement in recruiting, providing scholarship funding and encouraging minority students to consider a career in dentistry.

What more needs to be done: More private funding for scholarships for minority students would allow the school to better compete with other dental schools for minority student talent. Mentoring as young as elementary school also is a great way to develop interest in the profession. Dentistry, as a profession, should be on the radar of school-age children just like medicine, nursing and all the other health care professions.

Importance of dentistry in health care: In addition to the evidence that links certain systemic diseases to periodontal disease, there are other diseases that present with oral manifes- tations or symptoms that the dentist often detects during routine dental examinations.

Role dentists play in educating people about teeth: In addition to talking to patients when they are present in the office, dentists can speak at churches, school events and organized community activities, as well as in casual conversations when the subject is appropriate.

Dental care recommendations for parents and children: Decrease the amount of processed sugars given to children and substitute with fruits. Limit soda and practice drinking more water until it becomes a habit. Don’t forget to brush and floss at least as often as you shower!

Many people have bad teeth because: Lack of adequate den- tal health education; inadequate information on proper diet and the limiting of processed sug- ars; perpetuation of negative experiences of others; using dental treatment as a negative reinforcement tool in children to promote positive behaviors; not taking full advantage of dental insurance that is avail- able; or lack of ability to pay co-payments or the full cost of dental care.

Children have cavities and tooth problems because: All of the reasons listed in the pre- vious question, in addition to the fact that many parents are unaware of the importance of good dental care of the primary (baby) teeth because they feel they will lose them anyway and grow new ones. The reality is primary teeth are of the utmost importance because they guide the secondary (adult) teeth into the proper positions. Diseased primary teeth can adversely affect the permanent teeth.

What needs to change: Increased knowledge of proper diet; scheduling dental appoint- ments regularly with the dentist, beginning as soon as the child begins to get teeth, so that by the time there is a full dentition, the child is comfortable with the dental office, the staff and routine dental health preventive procedures.

Role schools could play in dental health: Dental disease should be viewed and managed as any other childhood disease and the schools should be more proactive in the prevention component. In-service courses could be implemented annually to help administrators and classroom teachers understand the direct relationship between dental disease and poor academic performance.

How I unwind: Puzzles, such as Sudoku, Muddled or Hidden Words, either on my electronic devices or in puzzle books. I enjoy game shows, murder mysteries and some situation comedies on television.

A quote that I am inspired by: “Minds are like parachutes. They only function when they are open.” – Anonymous

Something I love to do that most people would never imagine: Digging in the dirt. I love growing and nurturing plants.

At the top of my “to-do” list is: Remembering to consis- tently thank God for all my blessings.

Best late-night snack: A Fuji apple and roasted almonds.

The best thing my parents ever taught me: To take pride in the quality of my work.

Person who influenced me the most: My mother, Jennie E. Wood Freeman, Dr. Carolyn C.W. Hines, my best friend, and my recently deceased older brother who was like a father to me.

Book that influenced me the most: “The Secret” by Rhonda Byrne.

What I’m reading now: “Traveling Light” by Max Lucado.

My next goal: To travel more.