NFL team owner, human trafficking and faith-based communities

Religion News Service | 3/8/2019, noon

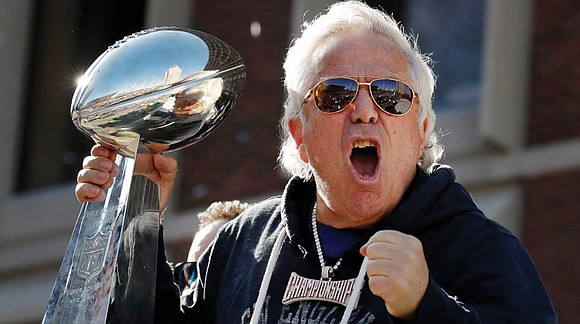

The news that New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft has been charged with soliciting sex and prostitution in a spa as part of a monthslong investigation into a massive human trafficking ring is dominating headlines for its shocking revelation about a legendary owner and current Super Bowl champion.

Mr. Kraft has denied any wrongdoing, but the scandal of human trafficking at the heart of the allegations is not any single person’s story.

Exposing and eradicating this global — and local — problem has been a primary goal for Raleigh Sadler, founder of Let My People Go Network, which works to engage churches in combating human trafficking. He is also the author of the new book “Vulnerable: Rethinking Human Trafficking,” which he wrote from his perspective as an evangelical Christian.

Religion News Service contributor Jamie Aten, executive director of the Humanitarian Disaster Institute at Wheaton College, asked Mr. Sadler about the Kraft scandal and about how faith communities can respond to human trafficking. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What was your reaction when you heard about Robert Kraft being charged with solicitation?

A: It’s easy to think that the only people that solicit prostitution are those who don’t fit Mr. Kraft’s mold — especially someone who seemingly has it all. It’s not clear if Mr. Kraft knew about the spa’s connection to a human trafficking ring. Regardless, the news (that came out of a police investigation into prostitution and sex trafficking) shines a light on the fact that those in prostitution can be victims of trafficking.

We must re-examine our assumptions. Many see nothing wrong with the solicitation of those in prostitution. Yet, this case highlights a horrible truth that many of those who are “in the life” are not there on purpose, or would not have chosen it if they had other viable options.

Anyone can be trafficked and anyone can be involved in trafficking. Trafficking happens when there is someone with power exploiting someone who is powerless.

Q: What might motivate someone like Mr. Kraft to be involved in something like this?

A: Though we are still finding out more details about this situation, in general, people’s misplaced desires can drive them to exploit others’ vulnerabilities. People who buy sex are often trying to fill loneliness or desire for companionship. However, others do so out of a need for power or control.

Q: How widespread is human trafficking?

A: According to the Global Slavery Index, as many as 40.3 million people are impacted by various forms of human trafficking. Whether they are trafficked for sex in an illicit massage parlor, forced to work in an orange grove or coerced to be a live-in domestic servant for little to no pay, people are commercially exploited around the world. Cases have been reported in every country as well as every state.

Q: How do you hope the NFL will respond?

A: The NFL is facing a dilemma. With all of the players that have been involved in domestic abuse situations, and now with this sex trafficking situation, the NFL needs to stand for the dignity of people who are suffering. They need to require more from their owners, have higher expectations and expect more from their players. No matter how good a player is, people’s lives are of more value than any game.

Q: What can faith-based groups do about human trafficking?

A: First, as communities of faith, we must become adept at identifying those in our communities who are most susceptible to the lures of a trafficker. Once we discover those who are marginalized or stigmatized and enter into their lives, it makes us better positioned to identify where force, fraud or coercion — the means of human trafficking — intersects with their vulnerability.

We can learn the red flags. We have to stop seeing people through a transactional lens, where we view people as problems to be solved. Instead, through the context of relationship, we can see our vulnerable neighbors as people — people who can be loved.

Q: Can you give me an example of how a faith community has helped stop human trafficking?

A: A friend of mine is a pastor whose church in Ridgewood, Queens, in New York, works with immigrants in his community. One day he was handing out coats to the most vulnerable in the area. A young woman came in for assistance. He found out that she had a job at a massage parlor next door.

About a month later, someone told him about a brothel advertisement that had been shared on their community Facebook page. It was the same woman to whom he had given a coat.

He connected with local law enforcement who began an investigation. His suspicions were right. What began with one pastor recognizing a need eventually led to 24 illicit massage parlors closing.

Q: Anything else you’d like to share?

A: I want to see people all over the country realize that we may not be able to do everything, but we can all do something. But before I could ever be a part of the solution to human trafficking, I had to realize that I was part of the problem. I, too, was investing in a culture of brokenness, not through soliciting prostitution, but in the food I ate, the clothing I wore and the entertainment I consumed. I needed to repent from that.

Mr. Kraft may have been unintentionally perpetuating a larger systemic issue.

We have to really have our eyes open to the vulnerable around us. You will see most clearly the exploitation of vulnerability when you are focused on loving the vulnerable.