‘Silence is violence’

Pastor and author Dr. Brenda Salter McNeil talks about racial justice and faith

Adelle M. Banks/Religion News Service | 8/20/2020, 6 p.m.

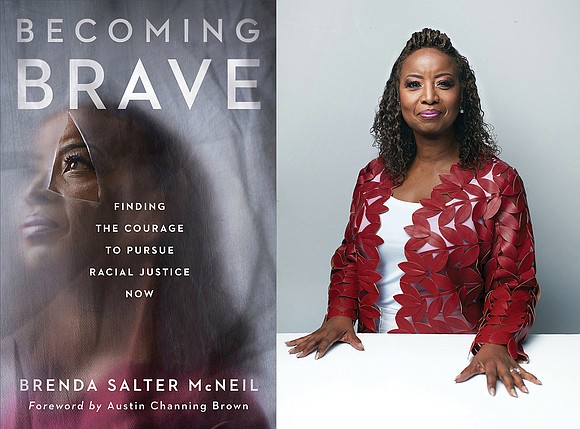

Dr. Brenda Salter McNeil has been on stages, in classrooms and pulpits, preaching for decades about bridging racial divides.

In her new book, “Becoming Brave — Finding the Courage to Pursue Racial Justice Now,” the associate professor of reconciliation at Seattle Pacific University said there is no more time to wait.

She holds up Esther, the queen in the Hebrew Bible who courageously interceded for her fellow Jews, as a role model for Christians to work toward racial justice. Without such steps, said the ordained Evangelical Covenant Church minister, young people could continue to lose confidence in the relevancy and the credibility of the church.

“How we manage this particular time in history is going to tell a lot about the future generations, regardless of their race and ethnicity,” she said. “So I’m saying to everybody, regard- less of our race, ethnic background or culture, this is a time for the church to be the church because people don’t believe us anymore.”

Dr. Salter McNeil, 64, added that protest can take many forms. As a high schooler in New Jersey, Dr. Salter McNeil said her mother forbade her from joining the demonstrations in the late 1960s and 1970s after the assassination of the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Still, she embraced the phrase repeated by her fellow students at demonstrations: “I’m Black and I’m proud.”

Dr. Salter McNeil talked to Religion News Service about joining protests as an adult, why she has become more selective in accepting speaking engagements and how reconciliation includes not only racial issues but language and sexuality.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You open your book “Becoming Brave” with the story of a young seminarian asking you, a longtime speaker on racial reconciliation, when you were going to talk about justice. What was your answer then, and would you answer differently now?

Yeah, I would answer differently now. The answer then was reconciliation, which, for me, included justice. It wasn’t a relational term for me. But what I would say now is that the more specific political, cultural, social justice issues must be addressed — not just alluded to. I’d be much more specific about that right now.

Your book highlights Esther as an example of a “warrior” who responded to a call for justice. How has your study of this Old Testament character affected your work as a Christian social activist?

She finds herself in a moment in history that demands her leadership, whether she was feeling ready to do that or not. I think we are living right now in the midst of a time in history that is demanding Christians to come to the table to speak truth to power, be that in our local congregations, in the way we vote, our social systems. That’s why her story is so compelling — because she was facing a defining moment. And I think we, too, are facing a defining moment.

In the wake of the killing of George Floyd in police cus- tody in Minneapolis, has your message about racial justice and reconciliation changed?

No. Silence is violence. And to watch a person be strangled to death within 9 minutes — I’ve been asked to preach a sermon in 10 minutes, which means nine minutes plus some seconds is enough time for a person to stop doing what they’re doing and reconsider another way. So I haven’t changed what I’ve said. I’m saying it even more clearly.

Are you more in demand or are you refusing certain speaking engagements that you once would have accepted?

Both. I am more in demand. I think there is a growing sense around the country and around the world that this is an unavoidable conversation. People are seeing those kinds of tragedies happen, and they are willing to now say that they have overlooked it and did not know how to respond to it.

With that in mind, I am being invited more. And I’m also saying no to the places where people really just need to have a person of color or a woman speaker to somehow look diverse without grappling with the real issues that require reconciliation and justice.

You wrote about being in Ferguson, Mo., for a clergy consultation after the 2014 death of Michael Brown, a young African-American shot by a white police officer, and unexpectedly being involved in a physical protest with younger activists.

This was unexpected because we didn’t know that there was going to be a decision that was going to affect the country around Eric Garner (when a grand jury decided not to indict the New York police officer who put Mr. Garner into a fatal chokehold).

I think at that point, as clergy, we were coming to learn how we could go back to our various cities and states and advocate around change.

I did not realize that that advocacy would be brought to a breaking point because of the decision around Eric Garner, that then made us go to the streets with the young people that were there in Ferguson.

How did it affect you?

It was life-changing because I do believe that when you get proximate to a situation, you experience it, you see it for yourself and you’re no longer having information filtered to you through people’s perspectives. It also was life-changing because I was in the middle of something that helped me to see the rage and the angst of young people and their need to see the people of God be in solidarity with them. They need to believe that we see injustice and it matters to us. And I felt as if I was on the right side of history in the moment.

You say that all Christians are called to be activists. What do you mean?

The Bible says that we have been entrusted with the ministry of reconciliation, and so it’s not like it’s an option to care or to pursue the work of reconciliation. That’s a part of what we, as Christians, are supposed to be distinguished by.

What does it mean for people to be Christian activists when they often have to be physically distant during the COVID-19 pandemic?

I think it’s challenging the idea that the only way you can protest is by being in the streets or being in a crowd of people. I think how we vote can be an act of protest. I think that the way we show up in our neighborhood and what we do to care for people around us is an act of protest.

COVID-19 is making us re-examine what it means to be present. And it’s not always just physical presence. I think we can show up in other ways.

You also speak of an expansive definition of reconciliation, moving beyond race to language. Why did you decide to learn to speak Spanish?

When we learn another language, we put ourselves in a posi- tion of needing other people’s help. And it puts us into a culture other than our own where we have to be the learner and not always the leader. When I was in Costa Rica, I had a Ph.D.

However, that doctorate does not show me how to go into the bank and make a transaction, because my language skills were limited. So it kind of levels the playing field, and it makes reconciliation reciprocal where there’s stuff I have to offer, but there are also things I need from people.

It also gave me great empathy for people who come to this country, documented or not, who are trying to navigate their way in a culture where they don’t speak the language. It’s extremely difficult.

Likewise, you also served as an advocate for your colleague Judy Peterson at Evangelical Covenant Church disciplinary hearings after she officiated a 2017 same-sex wedding. Why did you take that step?

Because I believe that all people are made in the image of God, and I feel like solidarity really means putting myself in situations where I stand in solidarity with the person or with an issue knowing that I, too, may get in trouble. It’s not a hashtag and I “liked” something on social media. It’s me showing up to be there with people in moments where I know it matters.

You speak about how it’s important for women and people of color who speak on reconciliation to “no longer put a smiley face on it.” How are you able—if you are able — to have a message of hope in the wake of the deaths of George Floyd and other Black people at the hands of police?

I believe that that is what the Bible is all about. That’s why the church can’t abdicate our role in this work because we are the people who have the message that the tomb is empty. That when you think it’s all over, God still brings life out of death.

And that’s the narrative that we have to bring to the world.