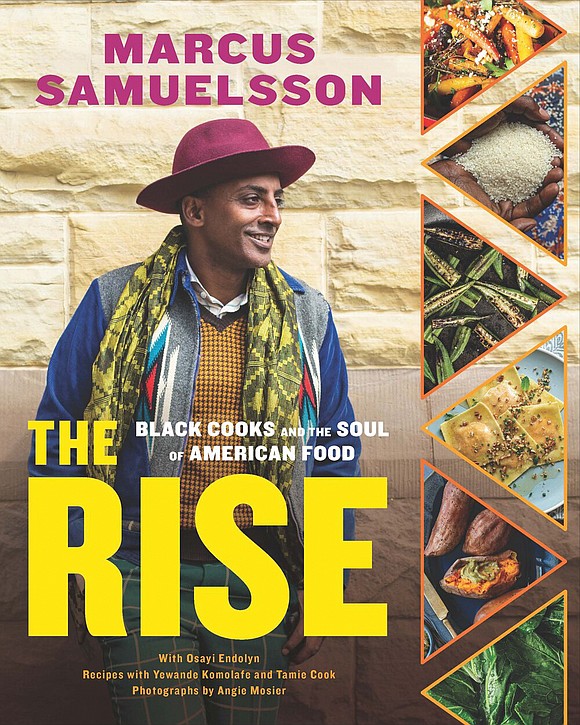

Chef Marcus Samuelsson celebrates Black chefs, food in new book

Free Press wire reports | 11/5/2020, 6 p.m.

NEW YORK - If anyone asks chef Marcus Samuelsson what African food taste like, he has a ready answer: Have you ever had barbeque? Rice? Collard greens? Okra? Coffee?

“All of that food comes from Africa, has its roots in Africa,” said the Ethiopian Swedish writer and restaurateur. “Everyone has had African-American dishes, whether they know it or not.”

Mr. Samuelsson is hoping to educate Americans and champion Black chefs in “The Rise: Black Cooks and the Soul of American Food” from Little, Brown and Company’s Voracious imprint.

The book has 150 recipes inspired by Black chefs, writers and activists, and includes profiles of 26. The recipes celebrate the legacy of Africa, the influence of migration and integration and where cutting-edge Black chefs are going next.

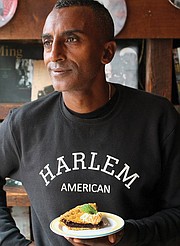

“When I look at American food and I look at the Black experience, we’ve done so much but almost got erased,” said Mr. Samuelsson, the chef of Harlem’s famed Red Rooster restaurant. “There’s never been a better time to tell those stories.”

The book — with essays by Osayi Endolyn and recipe development by Yewande Komolafe — is a rich mix of stories and food, from citrus scallops with hibiscus tea to oxtail pepperpot with dumplings. As Mr. Samuelsson writes in the introduction: “This isn’t an encyclopedia. It’s a feast. And everyone’s invited.”

Readers will learn how Los Angeles-based chef Nyesha Arrington’s cooking draws on family history from Mississippi and South Korea. They’ll learn it takes just 45 minutes to make Eric Gestel’s chicken liver mousse with croissants, a dish informed from his years cooking at the acclaimed Le Bernardin. And they’ll learn how Mashama Bailey is reinventing traditional Southern dishes.

“Our pasts are so unique and it’s so important to tell,” Mr. Samuelsson said. “We needed to tell our very layered and beautiful, non-monolithic journey.”

Mr. Samuelsson noted that many cookbooks celebrate European and Asian foods but hardly bring up Black dishes, meaning we know more about ricotta than ayib, the fresh cheese of Ethiopia.

“This is America’s past. So for me, as much as we learn about Japan, as much as we learn about Italy and Spain and so on, wouldn’t it be great to learn about our own food? This is America’s food,” he said.

Mr. Samuelsson compares the food in the book to popular music. He looks at New Orleans and hears the influence of France, Haiti, Africa and Spain — he hears jazz. Black food is no different.

“It comes from the continent first and then it lands here. And then, whether we went North or stayed in the South or went out West, it’s going to have a different journey — a different flavor profile to it — depending on who we met and who we got together with,” he said.

The book took four years to make and had to grapple with the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement. Mr. Samuelsson said in his author’s note that the effects of COVID-19 will stay in the Black community longer than elsewhere and that the nation must also fight the virus of systemic racism. But he marvels at the resiliency of the Black community and writes, “Black food matters.”

“We still will cook,” he vowed. “Black food has always been controversial because the way we were brought here to work, the food and the land. We have always had to do it through different lengths and a different set of rules.”

Readers will learn how wide and rich the food rooted in Africa can be, from the use of venison to pine nut chutney to roti. They’ll learn that benne seeds are a delicious alternative to sesame seeds and make a vinaigrette sing.

“Whether this is your first experience making African-inspired dishes or you’re familiar with them, my hope is this book will spark an interest — or continue one — and you’ll want to learn more about the people redefining and celebrating this cuisine,” Ms. Endolyn said.