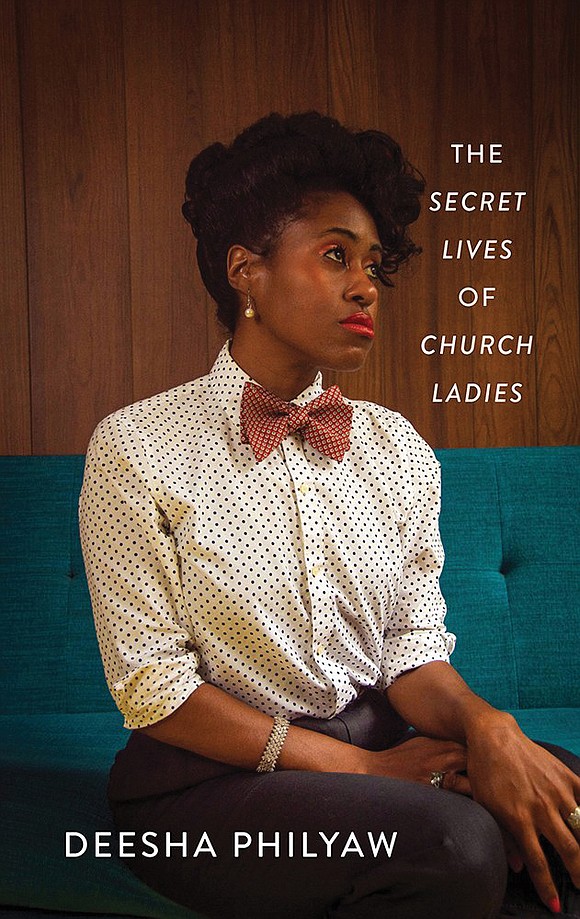

’The Secret Lives of Church Ladies’ is finalist for National Book Award

Adelle M. Banks/Religion News Service | 10/15/2020, 6 p.m.

For years, Deesha Philyaw, a Pittsburgh writer, editor and writing coach, has gradually crafted stories about church ladies — but these are not the stories you’d likely hear sitting in the pew of a Black church.

Now, her new book, “The Secret Lives of Church Ladies,” has been named a fiction finalist for the National Book Award. In it are nine stories that cross generations and families, tales of Black women whose lives are a mixture of religion, sex, love and grief.

There’s the single woman and the married man who first meet in the hospice facility housing their elderly Christian mothers and who later end up in the back seat of a car outside.

And the longtime best girlfriends who as teens dreamed of a double wedding with male mates but now have their

own sexual rendezvous together once a year. One still hopes for a man; the other questions God. And the girl whose mother regularly shares peach cobbler and herself with their married male pastor. The girl, now a teen, begins tutoring lessons and a liaison with the same pastor’s son.

Though the details may be invented, Ms. Philyaw, 49, said her book reflects the real-life “dissatisfaction and struggle” of some Black women raised in the church, but also the comfort and guidance many of them find in God.

“I see the book as centering Black women in their own stories of the tug of war they experience between their desires and what they may have learned at church,” said Ms. Philyaw, who no longer considers herself to be religious. “I want to be sure it’s the women who are centered and the church is sort of in their orbit as opposed to the other way around.”

Hours after learning her book was an award finalist, she spoke to Religion News Service about growing up in the church, writing about affairs and what she thinks her late mother and grandmother would think of a book that she would definitely give an “R” rating.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Congratulations on being named a finalist for the National Book Award. How did you react to that news?

Oh, the scream that I let out, let me tell you. I am so honored and thankful and just excited that people have connected with it the way they have. And I’m going to try not to start crying again.

Of all the topics you could have chosen for your first short story collection, why did you pick the secret sex lives of Black women and girls who had close or distant connections with the Black church?

They live in my imagination because I was a church girl. I grew up in the church. I grew up in the South. How do you navigate the really tight space that church can often bind us in when it comes to many things, but our sexuality in particular?

I was raised by my mother and my grandmother. And it was just their stories, their voices, their contradictions and all of my curiosity about them that has stayed with me.

In your acknowledgments, you thank “my mama and Nay-Nay for sending me to church and Sunday school all those years.” Where was that church?

Jacksonville, Fla., is where I was born and raised. And it was many churches. We talk about “the church” and we know the Black church isn’t a monolith, but in my collection, it’s sort of the traditional evangelical Black church. But for me growing up, it was numerous churches, numerous denominations: AME (African Methodist Episcopal); Baptist; Pentecostal; COGIC, which stands for Church of God in Christ; Missionary Baptist Church.

Though these are works of fiction, how would you describe them as far as how true to life they are and what they say about Black church women in general?

I’ll defer to the Black women who have said to me, “I know these women,” or “I am these women,” or “I used to be that woman,” or “I knew exactly who you were talking about in this story.” So I think it’s very true to life.

More than one of the nine stories features lesbian love, whether two grown women or a girl with a crush on her male pastor’s wife. Do you consider attitudes about LGBTQ people to be one of the bigger issues that Black churches continue to grapple with?

It’s one, but I really want to put it in context. Because there’s often these conversations that somehow Black people or the Black church are more homophobic than other folks. And so I don’t want to really put a fine point on that particular area. I think it’s part of a larger continuum of the binaries of who we can be. We can be the Madonna or the whore. We’re in God’s will or we’re outside of God’s will. It’s really a larger question of the church giving us so few options about who we can be and how we can be in the world and what it means to be good, what it means to be a man, what it means to be a woman. And certainly part of that is in terms of how you identify as queer or not queer. So that would be one factor.

On top of the many secrets in the sex lives of these characters, there also are what seem like superstitions, especially among their relatives — like the grandmother who dreams of fish and is then sure someone in her family is pregnant. What does that say about the influence of factors other than faith in the minds of some church ladies?

What’s revealed to us in dreams, those things we typically call superstition or old wives’ tales, they are drawn from our African roots. They get all tangled up when enslaved and formerly enslaved people adapted to Christianity and folded those practices in. So sometimes we can’t tell where one starts and one (ends). But as Black people, we own all of it. But too often, what we point to as superstition is presented as antithetical to Christianity or to godliness and many of us know that’s simply not true.

There are so many traditions of the Black church that you touch on in this collection — from the specific pews people sit in Sunday after Sunday to the special flower worn on Mother’s Day. What are you hoping to reveal about the ethos of these congregations?

I hope people see those things as the ways in which I am not bashing the church, that I still have fond memories of those kinds of traditions and that the church in and of itself isn’t the problem and so there’s a lot of good. There are reasons people cling to the church, very good reasons. There are reasons I have these memories and it’s not because I had bad experiences at church. It’s because I looked forward to Mother’s Day and knowing what those flowers meant and seeing who had the red flowers and who had the white flowers.

For those who are less familiar with these traditions, would you explain that tradition about the red and white flowers?

On Mother’s Day, you would wear a flower on your collar or your lapel, or you pin it to your dress. And you wear a red flower if your mother is still living and a white flower if your mother has passed away. Mother’s Day is a day where a lot of people come to church, usually or perhaps at the request of their mother. Maybe they don’t come any other time, but you know, mama or grandmama wants you to be there so you go and you wear your flower.

There is a story titled “Instructions for Married Christian Husbands.” It’s written in a different style than the others, a literal list that starts with “park at least one block away” from the home of the serial mistress. Why did you choose to include this?

I liked the concept of this serial mistress. But in the triad, if there’s a husband and there’s a wife and there’s this woman, she’s the one we hear from the least. She’s the most vilified. So I thought, what if I kind of subverted that and what if instead of her being the person on the margins, what if she controlled the narrative? I’m a big fan of what is called hermit crab essays in nonfiction, where you write an essay, but it takes the form of something ordinary. So I thought what if I did that with fiction and she wrote a little instruction manual for these guys? Now I can be creative and a little clever, but still tackle something that’s pretty serious.

How do you think your mother and grandmother would react to your fictional take on the secrets in the pews of churches — churches like the ones you attended with them?

I think they would be proud of me because they were just always proud of me. I don’t think there would be any exception about this book. Now, it gives me pause because there is a lot of sex in the book. But even with some of the more provocative content, I think they’d still be very proud and very happy about it.