Impact of attending Million Man March 25 years ago still felt today

Ronald E. Carrington | 10/22/2020, 6 p.m.

Twenty-five years ago on Oct. 16, 1995, an estimated 1 million African-American men from across the United States descended on the Washington Mall for the historic Million Man March.

The march was called by Minister Louis Farrakhan, head of the Nation of Islam, who believed Black men of all faiths should gather for preaching, prayers and promise for the future.

However, media publicity during the yearlong run-up pushed politics onto the agenda, and the Million Man March became different things for different people.

Washington was panic-stricken.

At the time, African-American unemployment was nearly twice that of white Americans, with 40 percent of Black people in poverty and a median family income about 58 percent that of the median for Caucasians.

However, many white Americans and Washington business owners anticipated a threat — looting and damage to property — and they closed their stores in the area around the mall, consequently missing potential booming sales.

How wrong they were on all counts.

Minister Farrakhan gave a two-and-a-half-hour keynote speech that day, centering on self-improvement, Black lib- eration and racism in America. Other speakers included Martin Luther King III, Rosa Parks, Maya Angelou, the Rev. Jeremiah Wright and the Rev. Jesse L. Jackson Sr., founder of the national Rainbow PUSH Coalition.

At one point, comedian-activist Dick Gregory shouted from the podium, “I love you!” and the audience sang the Black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

Black men came together during the march to address their power as husbands, fathers, business and community leaders, as well as to discuss the pain of historic condemnation by the country’s judicial system, economic limitation and housing discrimination.

That sunny, yet brisk autumn day is remembered by hundreds of thousands of African-American men. The communal feelings of unity, warmth and calmness — stretching across all ages and socioeconomic classes from working class men, professionals, grandfathers, teens, cousins and little boys — radiated throughout the day as Black men from across the country met, shook hands, hugged, talked and prayed together.

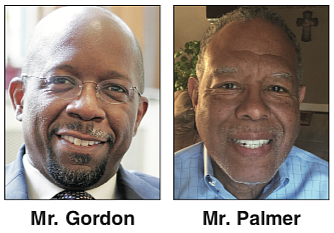

The significance of that day is still present with two Richmonders, one of whom now lives in Maryland.

Both were moved to action to make an impact in their respective communities.

Reginald “Reggie” Gordon, Richmond’s director of the Office of Community Wealth Building, was senior associate general counsel of the National Red Cross in Washington at that time. As one of two Black attorneys at the Red Cross, he attended the march because he felt the need for Black men to come together during a time of so much negative news about African-American men. The media was reporting then 1 out of 4 Black men were in the prison system and they were the source of violence in their communities.

“This was an opportunity for Black men to come together to tell our story and be together,” Mr. Gordon recalled in a Free Press interview. The night before the march, his brother and friends arrived in Washington from Richmond and discussed the plight of Black men.

“The march was a ‘Day of Atonement,’ a pro-black male event, and it was reverent from beginning to end,” Mr. Gordon said. “Minister Farrakhan wanted us to focus on ourselves — our lives, our history, our background and values — rather than on what the world was saying about us.

“The march’s message was crystal clear: What is your place for healing our people? Start with yourself, then your family and then your community,” he said.

Richmond native Jerry H. Palmer had moved to Maryland two years earlier in 1993 and attended the march with two friends, one, his Omega Psi Phi Fraternity brother, Lionel Lathan, and the other, Charles Mann.

Mr. Palmer, now retired as a DuPont business leader, compared the Mil- lion Man March to the famous 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his historic “I Have a Dream Speech.”

Mr. Palmer was 12 during the 1963 march and didn’t attend. But the impact of attending the march in 1995 remains with him to this day.

“To be part of an event with almost a million Black men from different fraternal organizations and churches from across the United States was powerful and impactful as it focused on togetherness,” Mr. Palmer said. “More importantly was the march’s spiritual nature and focus on how we could help each other.”

Mr. Palmer went back to his church, New Antioch Baptist Church of Randallstown, Md., and developed men’s groups — “Men with a Mission” and men’s fellowships with other churches exploring the spiritual nature of being a man—to help address Black men’s responsibilities to themselves, their families and their communities, which was brought up during the Million Man March. The groups he started are still vital today.

When Mr. Gordon returned to work, he had to explain the march to his white colleagues who were disturbed by his participation. He said he told them that the march had nothing to do with white America.

He left the Red Cross and moved in 1997 to Richmond, finding his voice in many ways. He became a fund developer with the United Way of Greater Richmond and Petersburg, helping to boost critical programs in both largely Black communities. In 2016, he became director of the city’s anti-poverty effort.

Now 25 years later, Mr. Gordon and Mr. Palmer both said they are grateful for experiencing the historic and uplifting march. They said they will always remember the ocean of Black men across the Washington Mall as far as the eye could see, hold- ing each other’s hands, praying and crying with joy, laughing and smiling, standing together in silence, understanding 3 out 4 Black men were not in jail and were assets to their communities.

“There was an afterglow from the march,” Mr. Gordon said. “Many of us felt like elders. Many men I talked to told me that they would walk up to young brothers on the street and tell them to pull up their pants—sagging was popular— or talk to them and tell them how to carry themselves. That responsibility was amplified after the march.”