‘Forgotten First:’ A look at four – and more – NFL trailblazers

9/16/2021, 6 p.m.

In this era of racial reckoning, it’s not only appropriate but significant that the stories of NFL trailblazers be told.

Keyshawn Johnson, the 1996 top overall draft pick by the New York Jets and now a host of ESPN’s morning program “Keyshawn, JWill and Max,” has done so.

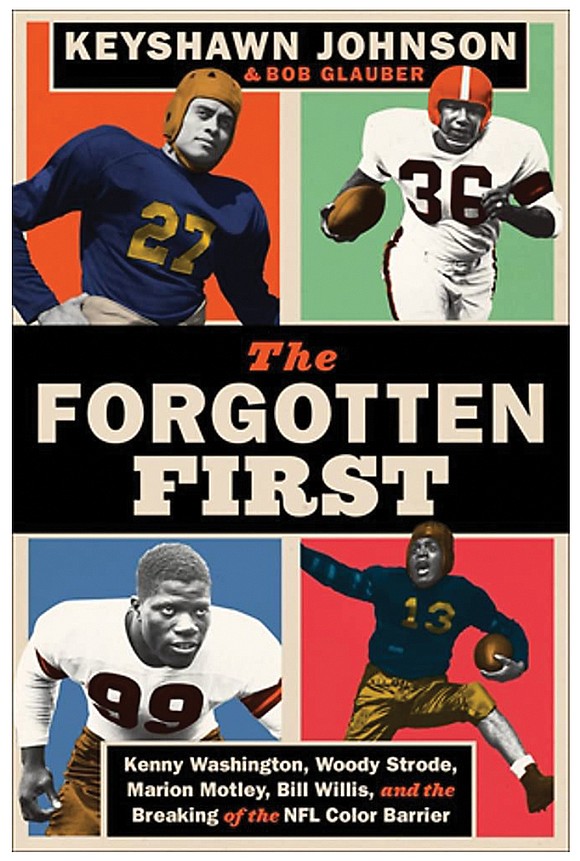

Collaborating with Bob Glauber, the Newsday columnist and 2021 recipient of the Bill Nunn Jr. Award by the Pro Football Writers of America for outstanding longtime reporting, Johnson has authored “Forgotten First.” The book is an enlightening and often anger-inducing documentation of an ugly period in pro football history.

And it’s a tribute to four men who broke the color barrier in a sport in which 70 percent of the players now are African-American: Kenny Washington, Woody Strode, Marion Motley and Bill Willis.

“It’s close to home. It’s an educational vehicle for those that have a lack of education on how minorities were reintegrated into the National Football League a long time ago,” Johnson says.

Johnson and Glauber pay tribute to others who helped integrate the game, particularly Paul Brown, probably the greatest football coach and innovator. Brown never saw color, and in 1946 he recruited Motley and Willis for his Cleveland team in the All-America Football Conference even as Washington and Strode were about to make a breakthrough in the NFL.

“He never thought of himself as doing anything other than signing the best players,” Bengals owner Mike Brown, the son of Paul Brown, says in the book. “He didn’t think of (himself) as someone who merited credit as a civil rights leader. He did it just because he thought he was doing the right thing.”

The authors also make cogent observations about those who blocked integration, notably former Washington franchise owner George Preston Marshall, the leader of the anti-minority movement within the league that other owners silently backed. A monument outside of RFK Stadium in Washington honoring Marshall was taken down last year.

“George Preston Marshall was an unapologetic segregationist who greatly impacted the NFL in terms of keeping African-American players out of the league,” Glauber says. “At the time he owned the team, Washington was the southern- most franchise in the country, and Marshall was adamant about not having Black players because he believed they would alienate his fan base.

“The other owners simply did not push back, and after the 1933 season, there were no Black players in the league. In hindsight, Art Rooney Sr. called it the biggest mistake of his life as an owner.”

Even after reintegration began in 1946, Mar- shall refused to sign African-American players. It was only after pressure from the upper reaches of President John F. Kennedy’s administration in 1961 he finally relented.

One of the best chapters of the book, published by Grand Central Publishing and available on Sept. 21, discusses the relationship between Jackie Robinson, famously the first Black player in Major League Baseball in 1947, and his UCLA teammates Washington and Strode. At one point, the trio were referred to as “Three Dark Horsemen” in a play off of Notre Dame’s “Four Horsemen.” They were that good.

For all of their success, particularly by Wash- ington, the first Bruin to lead the nation in total offense and an All-American, the NFL wasn’t about to draft an African-American in 1939. Not even the best player in the country.

There would, of course, be success on the pro level for Washington and Strode, though not like Motley and Willis, who were inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame after their exemplary careers. Strode became better known as an actor. Washington, plagued by knee woes, was the forerunner of backs such as Bo Jackson and Gale Sayers, who also were other-worldly athletes with shortened careers due to injuries.

But Jackson and Sayers faced nothing like the racism the “Forgotten First” men did. Thanks to Johnson and Glauber, their stories — and hopefully some lessons learned — will register with readers.

“We didn’t write this book because of the country’s racial reckoning over the last two years,” Glauber explains. “We wrote it because these four pioneers truly have been forgotten by history, and people need to know the names Washington, Strode, Willis and Motley as much as they know Jackie Robinson.”