New book reveals details about Mary Lumpkin and the slave jail that became VUU

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 4/7/2022, 11 p.m.

The stories of enslaved Black women largely have been erased from American history. While a majority of Americans likely know the name of a few exceptional women such as escapee Harriet Tubman, who returned to Maryland to lead others to freedom, the lot of ordinary women who bore children who often were seized and sold is unknown.

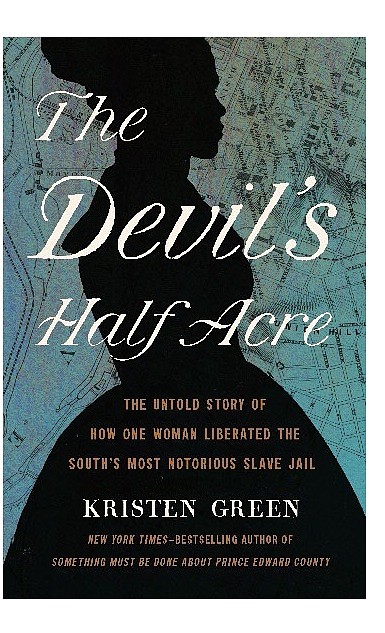

Journalist-turned-historian Kristen Nichole Green is filling in the blanks with her new book, “The Devil’s Half-Acre: The Untold Story of How One Woman Liberated The South’s Most Notorious Slave Jail.”

To be released Tuesday, April 12, the book explores the life and times of Mary Lumpkin, the enslaved concubine of Robert Lumpkin, the formidable and often brutal slave trader whose operation in Richmond’s Shockoe Bottom was so notorious for the horrific conditions in which slaves were kept that it was dubbed the “Devil’s Half-Acre.”

As Ms. Green recounts, Ms. Lumpkin inherited the jail after Mr. Lumpkin died following the Civil War. And she helped a white Baptist missionary turn the slave jail into “God’s Half-Acre,” a school for freed Black people that, by the turn of the century, would become Virginia Union University.

Today, the school recognizes Ms. Lumpkin as the “Mother of VUU.”

But the story also is about enslaved women and the slave trade. Because so little is known about Ms. Lumpkin, Ms. Green has interwoven a rich narrative about the trials and tribulations that Black women faced in general during that period and about the slave trade itself, which impacted and continues to impact the lives of tens of millions of people.

Ms. Green provides a portrait of Ms. Lumpkin, while also helping people understand the emotional and physical challenges that such women endured, including the all too common experience of being raped by their masters.

The book is already winning praise.

“Every Black woman must read (this) phenomenal book,” stated Jodie Patterson, author and chair of the Human Rights Campaign Foundation. “It is our story – a true story, an erased story – of sisterhood and resistance.”

“A remarkable achievement,” stated Beth Macy, author of the bestseller “Dopesick,” in praising Ms. Green for reconstructing Mary Lumpkin’s life “from a historical record that has sought to erase the contributions of Black women at every turn.”

A Farmville native now living in Richmond, Ms. Green said the research for her book was a challenge.

“During slavery, white enslavers intentionally erased the lives of enslaved people, changing their names and omitting them from important documents,” she said.

Ms. Lumpkin also “left no personal records, no diary of her thoughts – none that I could find anyway,” Ms. Green continued. “I spent years gathering tiny tidbits about her,” including letters that Ms. Lumpkin wrote and books that referenced her.

Ms. Green learned that Ms. Lumpkin, a Black woman with a light complexion, was born around 1832 on a plantation in Hanover County and apparently was sold to Mr. Lumpkin when she was around 8. By age 13, she had borne Mr. Lumpkin’s first child and would have four more.

The author also tracked Ms. Lumpkin through U.S. Census records to learn about her relocation to Philadelphia before the Civil War and the education of two of her daughters at a Massachusetts school. That allowed Ms. Green to describe how Black women sometimes were able to negotiate with their enslavers to secure a measure of independence and even freedom for themselves and their children.

“I used property records to determine that she bought a house in her name in Philadelphia where she would move her children to freedom,” Ms. Green said.

Ms. Lumpkin, however, returned to Richmond after the Civil War and remained with Mr. Lumpkin until his death in 1866 during an outbreak of typhoid.

Ms. Green also searched newspaper advertisements to learn about Mr. Lumpkin’s business and tracked down his will in the Richmond Circuit Court records. He left all of his property to Ms. Lumpkin, including the slave jail that had been converted to a hotel after Richmond’s capture by Union troops on April 3, 1865, just days before the Confederates’ formal surrender at Appomattox on April 9, 1865.

“Little by little, I was able to stitch together the life of a woman about whom very little was previously known,” Ms. Green said. She built a family tree and tracked down the descendants of the intrepid woman, who would later move to New Orleans and then live out her days in an Ohio community. Ms. Lumpkin died in New Richmond, Ohio, in 1905, six years after VUU began operating on its newly built campus in a section of Richmond known as Sheep Hill.

Ms. Green said she first learned about Ms. Lumpkin while on a newspaper assignment to report on the African Burial Ground that sits across from the now buried site of Lumpkin’s Jail at 15th and Broad streets. She said a magazine article she read for background described the jail and noted that Mr. Lumpkin had children with an enslaved woman who acted as his “wife.”

“I wondered what that meant,” Ms. Green said, “and I set out to learn more about her.”

Her extensive research provided her with insight and enabled her to see how remarkable Ms. Lumpkin was despite spending much of her life in Richmond living in the residence at the slave jail.

“I marveled at Mary Lumpkin’s ability to educate her daughters and to free her children. I thought about what it was like to live in a slave jail and encounter the people who passed through it,” Ms. Green said.

The book, which is being published by Seal Press, an imprint of the Hatchette Book Group, one of the nation’s major publishers, is the second for Ms. Green.

Her first book, “Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County,” made the New York Times list of best sellers after its release in 2015. A combination memoir and history, the book focused on the five-year shutdown of the Virginia county’s public schools and Ms. Green’s family’s role in creating a private academy for white children like herself.

A graduate of the University of Mary Washington, Ms. Green said she became smitten by journalism while earning her bachelor’s degree in American studies. She would later earn a master’s in public administration from Harvard’s Kennedy School.

Now the married mother of two daughters, Ms. Green’s career in journalism took her to newsrooms in Virginia, Oregon, California and Massachusetts. She found her niche in reporting on inner-city and minority communities, writing on everything from gang violence to the lives of immigrants and refugees and the vital businesses they created.

During a stint with the San Diego Tribune, she spent four months in Guatemala learning Spanish in order to cover the inner city for the paper.

Friends have described her as fearless and willing to tackle unpleasant topics.

Her book on the public school shutdown in Prince Edward County that she said she lived through with little awareness is an example of her willingness to probe even her own family’s role.

She said when that book was published, “it is important to own the mistakes of the past. We have a lot of work to do in this country, grappling with unpleasant history.

“I felt there is nothing wrong with feeling shame or guilt about things your family has done in the past, to fess up and to talk about it,” she said. “I thought it was the right thing to do, to say what my family did was wrong and I’m sorry.”

In her new work, she is able to plumb the depths of slavery’s horrors, but also tell the ultimately positive story of “an enslaved woman who did something incredible. She used her agency to free her children and herself and to leave a lasting legacy in the school that she enabled to get a start in a slave jail she ended up owning.”