Water consumption is down but not the cost

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 8/18/2022, 6 p.m.

Why is the cost of drinking water going up?

One surprising reason is that people are using less water in their homes, businesses and factories in Richmond and across much of the country.

Consumption of public water has dropped an astonishing 28 percent in Richmond in the past two decades, according to the April Bingham, director of the Department of Public Utilities, reducing revenue and forcing the utility to raise rates to maintain financial stability.

The American Waterworks Association reports that consumption has remained flat or declined for two-thirds of the member companies in the face of population growth as consumers embrace the conservation philosophy.

Conservation or the concept of using less of a resource to get the same result has been all the rage in recent decades. Finding ways to reduce water use has fueled an engineering revolution, resulting in more efficient water-using appliances like washing machines and an overhaul of water-wasting industrial processes.

Today, efficient low-flow toilets can tackle the job with 1.5 gallons of water compared to old-fashioned toilets that used 5 gallons — a big deal given that flushing can account for up to 30 percent of a household’s water use, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Such efficiency draws praise and claims of savings for consumers who jump on the conservation bandwagon. For example, those who install low-flow toilets are told they could cut $230 a year from their water bills.

But there is little mention that the savings are illusory because the efficiencies create benefits for customers, but do not affect the expenses that producers of the water or the other resources must lay out to create the product.

But water, which everyone must have, is one of the best examples.

In 1999, DPU sold about 11.2 billion gallons of water, Ms. Bingham stated. Fast forward 23 years and sales have dropped to around 8 billion gallons as of June 30, she stated.

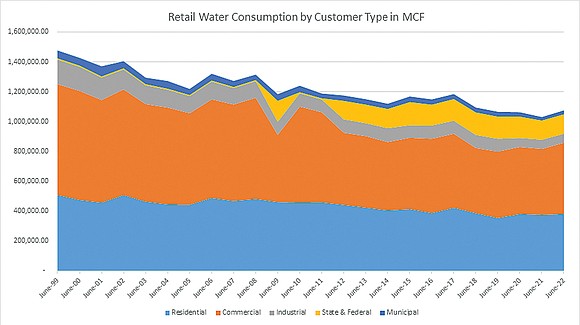

The chart shows that the big declines have occurred among three categories of customers: residential, industrial and commercial.

Ms. Bingham noted that such savings do not travel to DPU’s bottom line or change the costs of operating a plant that can generate 132 million gallons of drinking water daily

Estimates based on the 1999 rate for water indicate the decline in use has cost DPU a minimum of $8 million a year.

One the one hand, DPU is “committed to protecting the environment,” Ms. Bingham stated, “which includes promoting conservation and responsible water stewardship.”

One the other hand, it also needs to sell more water or raise the price to account for the reduction in use if the plant is to continue to produce quality water.

“A large portion of the water utility’s costs are fixed,” Ms. Bingham stated. The utility needs a certain amount of income to cover such expenses as chemicals, power, operations and maintenance, none of which fall because less water is sold.

Wages for DPU employees also do not go down when consumers reduce water use. Nor does DPU’s need to borrow and repay the debt to replace the aging network of piping, some of which dates back 100 years or more.

“Even if costs are held current levels,” Ms. Bingham stated, the utility would need to raise the monthly service charge or increase the price of the water” if volumes continue to fall, a trend DPU expects to continue “for the foreseeable future.”

She stated that the rate re-structure could reduce the impact on residential customers. DPU plans to conduct a study of the cost of service in 2023.

“We will work diligently to ensure rates are fair and adequate to cover costs,” she said.

There has been an impact already.

Water rates have increased three to seven times since 1999, though the cost is still negligible compared with the $1 a gallon that consumers pay for filtered, bottled water.

In 1999, residential customers paid 72.8 cents for 748 gallons, or .0009 per gallon, or one-ten thousands of a penny.

This year, the cheapest rate for residential is $2.85 for 748 gallons, or .0038 — essentially about one-third of center. (748 gallons is equal to 100 cubic feet of water or 1 ccf; city water meters measure use in ccfs.)

The impact also is felt on the cost of treating the water after it goes down the drain and into sewer piping. In 1999, the residential charge was $1.185 per ccf of wastewater; today the charge is $7.985 per ccf.

Overall, according to DPU, residential customers can expect to pay bills of more than $100 a month for tap water and wastewater service.