An honest accounting

Richmond writer reveals story of her family’s interracial heritage that has been shrouded in history

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 1/6/2022, 6 p.m.

Richmond novelist Ellen Glasgow gained fame for her realistic depictions of women, their relationships and their efforts to gain independence in a male-dominated world.

However, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author went to her grave in 1945 without ever publicly disclosing her family’s big secret — that they had Black relatives.

Now one of those relatives is telling about the complex relationships involving the Glasgows and her family, opening a window into the cross-racial ties that occurred among many Richmond families.

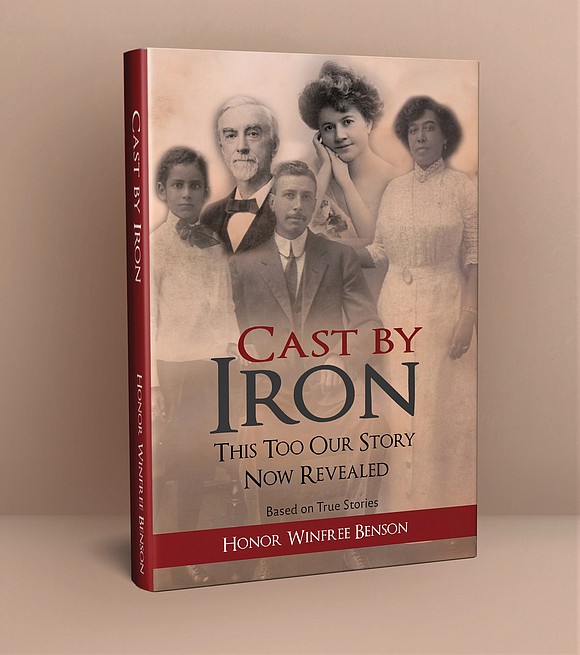

Honor Winfree Benson, a great-great-niece of Ms. Glasgow, grew up listening to her family’s stories about the connections. After years of library research in addition to the family information and document archive, she has recorded the relationship with the Glasgow family in a 650-page genealogy, not yet published, titled “We Are Richmond,” and a historical novel just issued titled “Cast By Iron.”

“This has been an untold story of Richmond,” said Ms. Benson, a proud member of a family of tradesmen, artists and educators. “I promised my family that I would bring it to light.”

What the former Richmond teacher found is that her great-grandfather, William Winfree, was Ms. Glasgow’s half-brother.

Ms. Glasgow’s father, Francis Thomas Glasgow, a manager of Tredegar Iron Works, had a long-running affair with a maid, Emma Jackson, who came from the Pamunkey Indian reservation to work in the Glasgow home.

Mr. Winfree, who lived to age 90, was one of two brothers born from that affair, Ms. Benson said, but was the only one to have children.

While initially part of the Glasgow household, Mr. Winfree was sent at age 3 to live with a Black woman, Mary Winfree, Ms. Benson said.

Mr. Glasgow, though, met regularly with his Black sons to provide social and financial support, she said. Mr. Glasgow and his white children, including Ellen Glasgow, periodically met with his Black offspring, meetings that his white children continued after his death, according to Ms. Benson.

Mr. Glasgow also ensured his Black sons had education and were trained in skilled trades, though he did not include them in his will, Ms. Benson said. She said it is not clear if Mr. Glasgow set up trusts for his two Black sons as he had for Ms. Glasgow and her siblings.

One of Mr. Glasgow’s white sons, Arthur, who became a prominent gas works engineer, sought through his will to benefit any grandchildren of his father and their descendants. But none of the proceeds of Arthur Glasgow’s estate apparently have gone to his Black relatives, Ms. Benson said.

Arthur Glasgow died in 1955, but a trust he had set up provided a combined $125 million to Virginia Commonwealth University and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in 2011, according to Ms. Benson.

Today, Ms. Benson believes that she and her sister, Hope, are the last remaining members of the Glasgow family, which could make them heirs of Arthur Glasgow’s estate. The Richmond Circuit Court authorized DNA tests to verify the connection, and Ms. Benson said legal contact has begun with representatives of Arthur Glasgow’s trust.

Ms. Benson said her family tree also includes ties by marriage to a once prominent Jewish family, the Marx family, who were significant Richmond bankers and physicians.

Ms. Benson has published the first two books of a five-part historical novel titled “Blood of a Rose” about the Marx family and her other blood lines from the American Revolution through the Jim Crow era.

She said that she has found her family’s story is woven into the fabric of a host of ethnic and religious communities, including “the American Indian, Black, white, Calvinist, Catholic, Pentecostal, Episcopal and Jewish.”

“What I am hoping,” she said, “is that what I have written will bring a little more insight into the full story of Richmond and give something to those whose history was completely lost.”