Richmond man seeks parole after nearly four decades in prison

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 8/24/2023, 6 p.m.

Since 2002, the Virginia Parole Board has approved the release of 69 people who were convicted of murder, including some serving two life sentences.

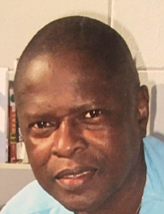

Marvin M. Mundy, who already has served 36 years for his role in the 1988 murder of the night manager and a guest at a Henrico County hotel, is keeping his fingers crossed that he will be next.

“I believe I’ve served long enough,” said the 60-year-old Richmond native, one of the dwindling number of inmates who remain eligible for release as their convictions occurred before 1994 when Gov. George Allen gained General Assembly approval to abolish parole.

He is one of more than 3,000 incarcerated people who are applying for parole in a state with a tough policy of rarely granting release, even to those who no longer pose a threat to others.

Mr. Mundy, whose supporters include Department of Corrections employees, is one example.

He believes he has a powerful case to be granted freedom and has put it in writing with help from the Virginia Capital Case Clearinghouse (VCCC) at Washington and Lee University Law School.

According to the VCCC report, there are multiple reasons why Mr. Mundy should no longer be in prison.

Among them is the key role he played in saving the lives of two Department of Corrections employees, including a former warden at the Buckingham Correctional Center and a guard at the Greensville Correctional Center.

In 1996, he closed a door to keep inmates from further injuring Buckingham Warden Eddie Pearson, whose face had been slashed with a knife. Three years earlier, Mr. Mundy pulled away an inmate as the inmate tried to choke the life out of a Greensville guard.

Mr. Mundy also has expressed deep remorse for his crimes in a personal letter to the board, in which he stated that he left behind the immature person he was when came.

Instead, by his actions, he wrote, he has shown that he has been “on a journey of self improvement.”

Along with becoming a licensed barber and cutting other prisoners’ hair, the Muslim convert has obtained his GED, taken all the counseling programs the Department of Corrections has offered and completed vocational training for administrative clerk, auto detailer, cosmetologist, computer operator, drywall installer, forklift driver, paralegal and sound system installer.

Mr. Mundy also is credited with developing self-help counseling programs to enable fellow prisoners to take responsibility for the actions that put them behind bars, prepare for release and deal with parole rejection, according to the VCCC report.

The Parole Board has received emails and letters of support for his release from U.S. Congresswoman Jennifer L. McClellan and 14 employees of the Department of Corrections, including the assistant warden at Greensville, T. Jarrell, whose email to the Parole Board described Mr. Mundy as a “model offender and a man of excellent character.”

In addition, the VCCC report suggests that Mr. Mundy might have been wrongly sentenced to two life terms plus 36 years based on his conviction of being the mastermind of the botched robbery in which two were killed.

As the report details, two of the people convicted with him, Norris Timmons and Keith Cox, who already have been paroled, have recanted in statements to law enforcement their testimony pinning the blame for the killings on Mr. Mundy. They now say that Mr. Mundy did not shoot anyone that terrible night.

If he were released, he has a fully developed plan for where he would live. He has a fiancée waiting for him as well as a supportive family. He has a transitional residence waiting for him through the REAL LIFE program in Richmond that helps released individuals adjust to life outside prison walls.

And now that he is 60, he also is eligible for geriatric parole, about the only type of parole for adult prisoners that was not abolished.

But his chances of leaving prison anytime soon, despite his health issues, appear to be slim.

According 2022 statistics, the state Parole Board received more than 3,300 applications for parole, but granted only 78 releases or less than 3%. The board currently receives about 280 applications a month, but grants an average of only eight releases per month.

One reason the pace has slowed is that the Parole Board has only seven investigators to review cases, meaning that applications pile up. More than 2,000 still await review, board statistics show.

In addition, the five-member Parole Board has two vacancies. Given that at least three members must approval parole, that means an inmate currently must receive unanimous support to secure release.

The cost of keeping Mr. Mundy and others with records indicating they would not be a public safety risk is expensive. The Department of Corrections reports spending an average of $42,000 a year to house each of the more than 25,000 inmates currently in the various state prisons. That compares to the average annual cost of $1,600 for parole supervision, according to the department.

Other states push parole because of the cost differential, including rock-ribbed Republican Texas, where parole is granted to about 30% of applicants, or 10 times the Virginia percentage.

Mr. Mundy, who has seen the Parole Board release others with two life sentences and far less positive records than his, has made his annual application for parole.

He is still waiting to hear back from the board, but remains confident that he will one day receive the life-changing word that he will be allowed another chance to live in civil society.

“It can’t come soon enough,” he said.