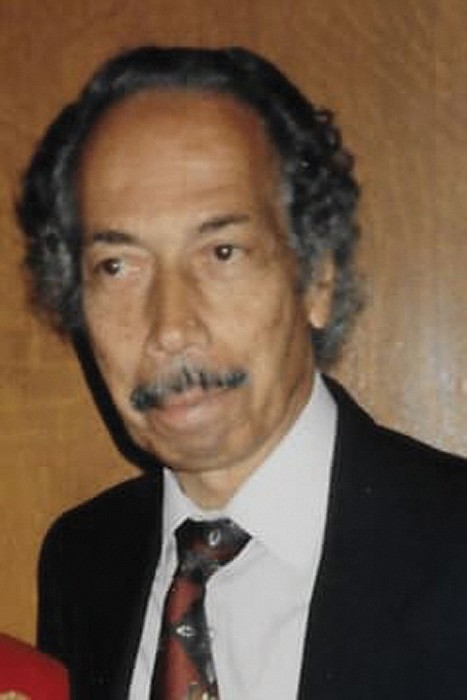

Earle P. Taylor, photographer and cultural arts innovator, dies at 94

Beneficiaries of his work included Last Stop Gallery and Pine Camp

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 1/5/2023, 6 p.m.

Earle Palmer Taylor, a renowned Richmond photographer who ran a nonprofit Shockoe Bottom art gallery for two decades and taught hundreds of people the art of taking and developing pictures at the city’s Pine Camp art center, has died.

Mr. Taylor died Monday, Dec. 26, 2022, according to Scott’s Funeral Home. He was 94.

The Richmond native who grew up in Navy Hill was to be paid final tributes at 10 a.m. Thursday, Jan. 5, at St. Paul’s Catholic Church.

Mr. Taylor was best known for portraits, including of such notables as sculptor Selma Burke, jazz artist Miles Davis and actress Jasmine Guy.

As he put it in a Free Press Personality feature, “I am a serious people watcher. That’s why I do photography.”

Part of a family of six children, he got his start with a camera while taking art lessons in an after-school program that Black sculptor Leslie Garland Bolling offered at the historic Craig House at 19th and East Grace streets.

Mr. Taylor initially took drawing lessons, but found that effort to create art too slow and frustrating. “I wanted to be too good, too fast,” he stated in the feature.

His life changed when he bought a basic photography kit that included a developer and a little light box and began teaching himself the rudiments. “I cannot paint as well as my camera can make picture,” he stated in the feature.

In an article about his life, he stated that he continued to hone his camera skills while serving with the U.S. Army Signal Corps and later took courses at a University of Virginia extension program offered in Richmond.

Turning professional, Mr. Taylor eschewed weddings and other group affairs and focused on developing a portfolio that could be displayed in art exhibits locally and across the country and overseas, particularly in Brazil and the Caribbean islands.

Seeking to help promote the work of what he saw as under-appreciated Black artists, he was a longtime member of the Richmond Chapter of the National Council of the Arts, a Black organization that started in Atlanta in 1959.

Mr. Taylor was instrumental in 1974 in organizing with other artists the Last Stop Gallery on Main Street near the Farmers’ Market to exhibit the works of local, regional, national and international artists.

In 1980, the Last Stop started opening on Fridays to the public, beginning a tradition that other galleries in the city later emulated. He became a key figure in operating the gallery until it closed in 1995. He was most proud of hosting in 1993 a touring show featuring the works of 18 internationally known Black artists.

Mr. Taylor also was well known for the photog- raphy courses he offered at Pine Camp. He began offering instruction in 1978 and continued them until he retired in 2014 at the age of 86. He also taught photography in Virginia State University’s Community College of Fine Arts.

He also was involved in Scouting and the Washington-based Very Special Arts, which provides art education for mentally and physically disabled children and adults.

“I have been about supporting the cultural, political and Catholic life,” he once said.

Mr. Taylor also participated in creating memorials to the Catholic Van de Vyver School and St. Joseph’s Catholic Church that he once attended in Jackson Ward, as well as his former stomping ground of Navy Hill. All were demolished, with Navy Hill razed to make space for government buildings.

He led the effort to create a small park on 1st Street that features a bell from the long-gone church, and wrote the inscription on a stone marker to the neighborhood that now sits at 4th and Jackson streets. The original inscription read: “Love and memories never die as days roll on and years pass by. Deep in our hearts memories are kept of the ones we loved and shall never forget.”

While he promoted Black artists, Mr. Taylor never wanted to be pigeon-holed. He was quick to say his forebears were “African, Cherokee, Powhatan and Irish. We’re all mixed and always have been.”

Mr. Taylor’s only immediate survivor is his brother, Willard Taylor.