On a mission: LifeNet’s quest to increase organ donations

Black Virginians make up half of the patients on the state’s organ transplant waiting list, despite accounting for 19% of the population

George Copeland Jr. | 9/21/2023, 6 p.m.

“Don’t take your organs to heaven — heaven knows we need them here.”

This phrase, commonly used by organ donation advocates, stuck with Donnetta Quarles-Reese when she first saw it on bumper stickers and license plates in her youth. It would stay with her in the decades that followed, when she agreed to donate the organs of her daughter Clarke Danielle and her husband Charles Michael after their deaths in 2007 and 2017, respectively.

“Something good has to come out of this,” said Ms. Quarles-Reese, who attempted to donate the fetal tissue of her first child who died early in life.

Since 2008, Ms. Quarles-Reese has worked to encourage others to become registered donors and spread awareness and information as part of LifeNet Health, a nonprofit that provides organs for transplants.

She credits the organization for helping her endure the grief she faced when her daughter passed.

Ms. Quarles-Reese, however, is a unique voice in a state where African-Americans are less likely to donate organs but are in greater need for these donations than other racial groups.

“There’s so many of us dying because we can’t get a kidney,” Ms. Quarles-Reese said. “There’s so many of us waiting because we can’t get a kidney, and we are the ones who are saying ‘no, no, no’ for whatever reason.”

“I want to dispel those myths and help us help ourselves.”

According to LifeNet Health, Black Virginians make up half of the patients on the state’s organ transplant waiting list, despite accounting for 19 percent of the population. Black Virginians also are less likely to donate the organs of family members to those in need, according to the group.

Also, some majority-Black areas in the state only register about 25 percent of registered donors compared to roughly 50 percent registration across all areas and populations in Virginia. These disparities mean that Black Virginians feel the obstacles associated with organ transplants more acutely than other groups.

Kia White, community affairs director for LifeNet Health, knows how important transplants are for those in need.

“Whenever I discuss what I do for a living, almost every conversation, there’s someone who has been impacted by dona- tion,” Ms. White said. “The chances are (that) many of us know someone that is either in need of an organ, that is on dialysis, or who received a transplant.”

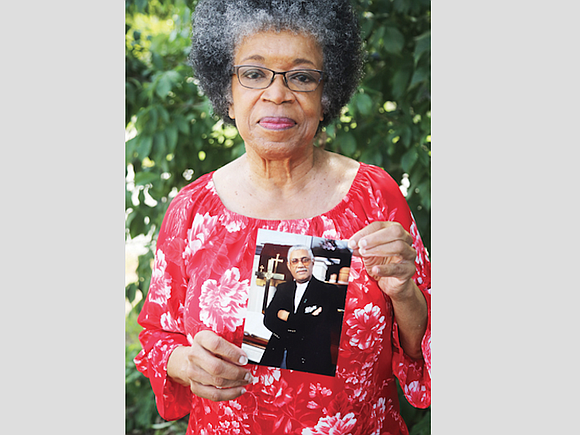

Saundra Rollins also knows firsthand the impact and value of organ donations for Black Virginians. Her husband, the late Dr. Darrel Rollins Sr. who was the pastor of 31st Street Baptist Church for 25 years, received a life-saving liver transplant in November 1994 after being placed on a waiting list earlier that year.

The experience led Dr. Rollins to become an enthusiastic advocate for organ donation in the Black community throughout his life. He died June 5, 2007.

Mrs. Rollins recalled that her husband had no hesitation in taking advantage of available transplants.

“We didn’t have a problem with it,” Ms. Rollins said. “Our view was if this helps someone else to live, we were for it.”

The process of organ donation and replacement has only improved in the decades since Dr. Rollins’ transplant. As explained by David Bruno, interim chair and liver transplant surgical director at VCU Health’s Hume-Lee Transplant Center, acquiring, approving and replacing organs has expanded across the years, thanks to better technology, improved organ screening and increased familiarity with the transplant process.

The end result of these changes has been largely positive, with nearly 43,000 organ transplants performed in the United States alone in 2022 according to the United Network for Organ Sharing. However, Dr. Bruno still sees a need for providers to ensure that marginalized people and communities are not left behind when it comes to life-saving procedures.

“We’ve known all along that we’ve got a problem in terms of disparities in health care,” Dr. Bruno said. “But really figuring out how to fix that, that should be hand-in-glove with the most important mission, which is saving someone’s life.”

Multiple causes for the disparity Black Virginians face with organ donations were suggested by Ms. Quarles-Reese, Ms. White and Ms. Rollins. This includes health conditions that are passed down through families, lack of access to health care and the presence of food deserts in certain communities that can lead to health issues or exacerbate already present issues.

Among reasons why so few Black Virginians agree to be organ donors may be due to a lack of experience and knowledge of the process, said Mrs. Rollins.

“It’s something relatively new when you think of the total scheme of things,” Ms. Rollins said. “Organ donations, I think, is something that people have to become accustomed to.”

Ms. Quarles-Reese said that some Black people also may be reluctant to become organ donors due to their religious beliefs. She also pointed to longstanding distrust between marginalized communities and the medical industry.

Various myths and misconceptions about organ donations require face-to-face advocacy and honesty to resolve, agree Ms. Quarles-Reese, Dr. Bruno and Ms. White.

“We’ve got to shake the notions that that’s the case,” Ms. Quarles-Reese said. “I don’t think you can do it any other way – it’s got to be us talking to us.”

Recent advocacy and outreach for organ donations have helped close the gap and widen acceptance among Black Virginians. LifeNet Health has seen a 19 percent increase in donations in Richmond communities. According to Ms. White, 50 percent of the kidneys that LifeNet Health donates in its Richmond service area now go to Black recipients, compared to 34 percent for other organ procurement operations in the United States.

LifeNet Health also works to engage the community outside its health-focused programs by partnering with organizations such as the Black History Museum & Cultural Center of Virginia and sponsoring back-to-school events to connect with the public.

“I believe the most we’re going to see out of these efforts is down the line when people are making informed decisions or more people are aware of the impact donation has in their community,” Ms. White said. “I think once we make that shift to where organ donation is viewed in a more positive light... that’s where we’re going to see the most improvement.”