Electoral college reform group eyes Virginia’s elections with hope

Charlotte Rene Woods | 6/26/2025, 6 p.m.

Could Virginia become part of a growing national movement to elect presidents based on securing the popular vote?

Though America is in its 47th presidency (with many presidents serving multiple terms), just five times has a candidate won the popular vote but lost the election. Although the majority of Americans voted for the losing candidate in those contests, the winners garnered enough Electoral College votes to ascend to the White House.

The most recent example of this came in 2016, when Democrat Hillary Clinton lost the presidency to Republican Donald Trump in 2016, despite winning the popular vote. In 2000, Democrat Al Gore was also defeated despite earning the popular vote, and lost to former President George W. Bush.

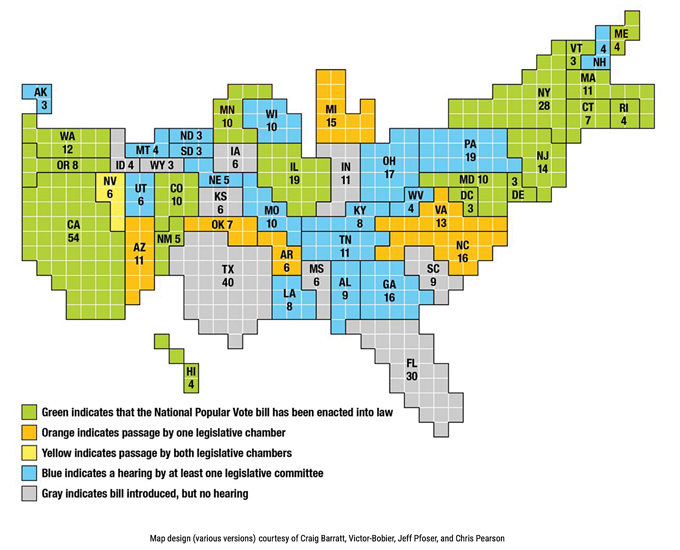

National Popular Vote, a bipartisan network of advocates nationwide, is examining whether the outcome of Virginia’s gubernatorial and House of Delegates elections could influence the state to join a growing coalition of states to support the popular vote. The organization has advocated for an interstate compact where participating states agree to honor whichever presidential candidate wins the national popular vote.

Any potential movement on the matter in Virginia would not get started until next year when the 2026 legislative session convenes. However it is a debate, typically led by Democrats, that Virginia’s legislature has explored before.

An effort for Virginia to join the interstate compact cleared the House of Delegates in 2020 before falling in the state Senate.

Lawmakers have also presented the measure again in subsequent years, but it has failed to advance.

So far, 17 states and the District of Columbia have agreed to a compact modeled by National Popular Vote. The agreement outlines how states’ electoral colleges would award all of their votes to whichever candidate gets the most votes nationwide.

Currently, presidential candidates need to win 270 electoral college votes to win — and each amount of electoral college votes is apportioned by the population size of each state. Enough states have signed onto the NPV measure to account for 209 electoral college votes, and should Virginia join, it would add 13 more.

Democratic gubernatorial nominee Abigail Spanberger declined to weigh in on whether or not she would sign a bill to join the compact and staff for Republican nominee Winsome Earle-Sears did not respond by the time of publication.

The popular vote proposal is not without pushback. The electoral college process often receives fresh scrutiny each time a presidential election occurs — and particularly when it benefits a candidate who failed to win the popular vote. But the electoral college is meant to be the counterweight to states with larger populations; each state, large or small, has a different number of electoral college votes allotted to them.

The conservative think tank The Heritage Foundation has defended the electoral college process. “Large cities like New York City and Los Angeles should not get to unilaterally dictate policies that affect more rural states, like North Dakota and Indiana,” the statement said. The Heritage Foundation has been a policy recommendation source for Republicans including Trump for the past several decades.

More than a rural/urban divide, sometimes electoral college debates fall along partisan lines too.

National Popular Vote has bipartisan members, while groups such as The Heritage Foundation support conservative and Republican candidates and coalitions nationwide. Cities such as New York City and Los Angeles represent predominantly liberal-leaning large localities in large U.S. states, which proponents of the electoral college argue could carry too much weight without it.

But former chairman of Michigan’s Republican Party Saul Anuzis said the idea of reform shouldn’t be partisan. He also serves as a National Popular Vote advisor.

“This isn’t a Republican or Democratic idea — it’s a small-d democratic one,” he said. Anuzis noted that presidential candidates focus on states that are considered swing states during election cycles, instead of engaging more deeply with voters nationwide.

Though a politically purple state, having oscillated between partisan control of its legislature and governorship, Virginia has not been as frequent a campaign destination for presidential hopefuls as other states have been.

“When the compact kicks in, you’d see candidates campaigning for votes in Richmond, Roanoke and throughout Virginia, not just Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Arizona,” Anuzis suggested.

“That’s how you rebuild trust and make elections feel like they belong to everyone.”

This story originally appeared on VirgniaMercury.com.