Latest Baseball Hall of Famer shares history with No.42

4/21/2017, 6:45 a.m.

African-American baseball Hall of Famers Tim Raines and Jackie Robinson have more in common than just immense baseball skills.

Both also are linked geographically to steamy Sanford, Fla.

And then there’s the coincidental connection to the Canadian chill of Montreal.

Raines, who was voted into the prestigious Baseball Hall of Fame in early January during his 10th and final year of eligibility, has mostly fond memories of Sanford, where he was born and grew up.

As a fleet young athlete, he established himself at Sanford Memorial Stadium playing for Seminole High School and other youth teams, attracting droves of pro scouts.

By contrast, Robinson’s memories were not as warm and fuzzy regarding the Central Florida city.

It was in Sanford in 1946 that Robinson was denied the right to take the diamond for fear of arrest during a spring training exhibition game at Sanford Field, located at the same site as the current Sanford Stadium.

The bigoted, embarrassing incident drew much attention in the biopic “42” about Robinson’s heroic rise against oppression to break the color barrier in Major League Baseball.

But more on that later.

First, some background on Raines.

Known as “Rock,” the 5-foot-8, 160-pound switch-hitting outfielder played most of his 13-season career with the Montreal Expos. A seven-time All-Star, Raines led the National League in hitting in 1986 (.334) and was a four-time stolen base champion, with a whopping 90 in 1983.

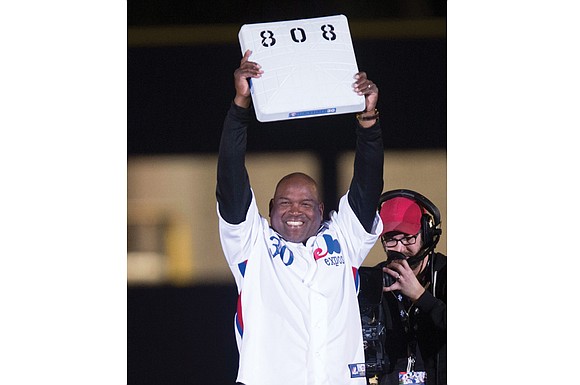

In 2,502 games, Raines collected 2,605 hits and 808 stolen bases, while hitting .294.

Raines was welcomed into the Hall of Fame on Jan. 18, along with infielder Jeff Bagwell, who played mostly with the Houston Astros, and Puerto Rican-born catcher Ivan Rodriguez, who played mostly with the Texas Rangers.

Formal induction ceremonies will be July 30 in Cooperstown, N.Y., home of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

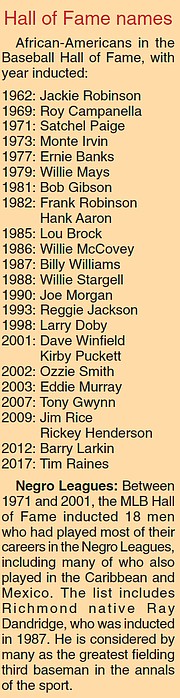

While Raines is the most recent African-American to be voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, Robinson was the first in 1962.

Success wasn’t guaranteed for Robinson along his hazardous path of shattering baseball’s color barrier in 1947 with the Brooklyn Dodgers. While resistance was tough in Sanford, Robinson wasn’t the lone African-American on Brooklyn’s AAA farm team, the Montreal Royals.

Robinson signed with Brooklyn in October 1945. In January 1946, another African-American player, pitcher John Wright, signed with Dodgers owner Branch Rickey. Both Robinson and Wright were assigned to the Royals roster for 1946 spring training.

There were a few Brooklyn-Montreal intrasquad-type games at Island Ballpark in Dayton Beach, Fla., before the infamous March 5 exhibition game in Sanford. City officials warned the Dodgers brass that white and black players would not be allowed on the same field. The Dodgers knuckled under to city officials and neither Robinson nor Wright played.

The team’s remaining spring games were moved to Daytona Beach, 44 miles northeast.

Soon after, Robinson went with the Royals to Montreal while Wright, who had not adjusted well to conditions on and off the field, rejoined the Negro League’s Homestead Grays.

In his one season in Montreal, Robinson hit .349, stole 40 bases and led the Royals to the International League pennant.

The next year, in 1947, he joined the Dodgers in Brooklyn as a 28-year-old rookie.

By comparison, Raines was just 21 when he made his debut with the Montreal Expos in 1979. Raines’ ascent to the top of the sport couldn’t have gone more smoothly. For that, he can thank Robinson, among others.