Farewell to the champ

Muhammad Ali fought for justice, equality and title

Free Press staff, wire reports | 6/10/2016, 5:38 a.m.

More than 62 years ago, an anonymous bicycle thief in Louisville, Ky., unknowingly set in motion the amazing career of a boxing legend and remarkable world figure who would live up to his self-billing as “The Greatest.”

Muhammad Ali • The Greatest

Farewell to the champ

A shaken and angry 12-year-old Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., wanting to report the crime, was introduced to Joe Martin, a police officer who doubled as a boxing coach at a local gym..

The officer advised the youth to learn to box first before seeking revenge, and young Cassius, who would later change his name to Muhammad Ali and his religion to Islam, found his future at Martin’s Gym.

Mr. Ali would rise to become a repeat heavyweight champion and much more.

Bold, charismatic and outspoken, the defiant one dubbed the “Louisville Lip” also would became a symbol of black liberation as he successfully stood up to the U.S. government by refusing to go into the Army as a violation of his adopted Muslim faith, adding his name to the roll call of black activists like baseball great Jackie Robinson, football and singing great Paul Robeson and tennis star and Richmond’s own Arthur Ashe.

Later, Mr. Ali would travel the world, raising money for charity and relief efforts, despite battling Parkinson’s disease that made him shake uncontrollably, becoming one of the most recognizable figures across the globe on par with Nelson Mandela.

Always a devout Muslim after his conversion, he would at one point use his celebrity to secure the release of 15 American hostages from Iraq, when it was still under the rule of Saddam Hussein.

Tributes to Mr. Ali’s stature, courage, generosity and character have poured in following his death at 9:10 p.m. Friday, June 3. He died in a hospital in his adopted home of Scottsdale, Ariz., of “septic shock,” a complication of the Parkinson’s he had fought for three decades.

As the world mourns, his family plans to carry out his funeral wishes in his hometown of Louisville this Friday, June 10.

Following a private funeral the day before, his body will travel in a motorcade along the avenue that bears his name. The procession will wind through his boyhood neighborhood and down Broadway, the same avenue where a parade 56 years ago celebrated the brash young man who had won a gold boxing medal at the 1960 Olympics, opening the way to his professional career.

The procession is to be followed by a memorial service open to the public that will be held at Louisville’s KFC Yum! Center in downtown. Eulogists will include former President Bill Clinton, comedian Billy Crystal and sports television host Bryant Gumbel.

The ceremony will be led by an imam in the Muslim tradition but include representatives of other faiths. Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch, for example will represent Mormons.

“Muhammad Ali was clearly the people’s champion,” family spokesman Bob Gunnell said, “and the celebration will reflect his devotion to people of all races, religions and nationalities.”

As one of the best-known figures of the 20th century, Mr. Ali did not believe in modesty and proclaimed himself not only “the greatest” but “the double greatest” during his heyday. In 1978, DC Comics even featured Mr. Ali and Superman as partners in a comic book.

Americans had never seen an athlete like him, a man with lightning-fast feet, a quick knockout punch and unrepentant words.

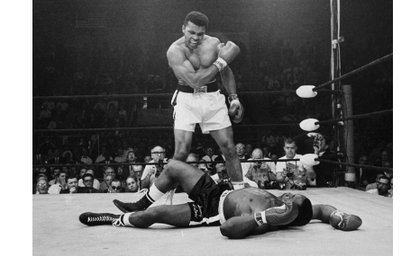

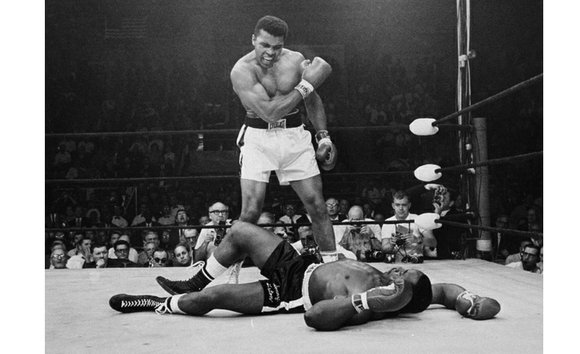

He was heavyweight champ a record three times between 1964 and 1978, taking part in some of the sport’s most epic bouts, dethroning and eclipsing champions like Sonny Liston and George Foreman and winning boxing immortality with his battles with former champion Joe Frazier.

In his heyday, Mr. Ali was cocky and rebellious and psyched himself up by taunting opponents and reciting original poems that predicted the round in which he would knock them out. The audacity caused many to despise Mr. Ali but endeared him to millions who adored him for his ability “to float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.”

“He talked, he was handsome, he did wonderful things,” said George Foreman, a prominent rival, who lost the heavyweight title to Mr. Ali in the 1974 “Rumble in the Jungle” in Zaire “If you were 16 years old and wanted to copy somebody, it had to be him.”

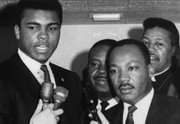

Mr. Ali’s emergence coincided with the American civil rights movement and his persona of a rebel offered youths something they did not get from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and most other leaders of the era.

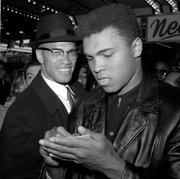

The day after conquering then-champion Sonny Liston and winning his first world heavyweight championship in 1964, Mr. Ali announced he had joined the Nation of Islam under the guidance of Malcolm X and had shed his ‘’slave’’ name of Cassius Clay, shocking the country.

Three years later, he propelled the anti-war movement to new heights by refusing to be drafted into the U.S. military to fight in Vietnam. He was convicted of draft evasion, banned from boxing and stripped of his heavyweight title.

When asked about his stance on the North Vietnamese, Mr. Ali famously said, ‘’They never called me nigger. They never lynched me. They didn’t put no dogs on me. They didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father.’’

His decision to stay out of the war later won a major decision from the U.S. Supreme Court upholding his position and wiping out his conviction, and with that, Mr. Ali had defeated what many saw as a racist system.

It would have been easier and more lucrative for Mr. Ali to keep quiet and go along with what many in white society wanted from him, said his longtime friend and sports commentator Howard Cosell. They wanted ‘’a white man’s black man,’’ Mr. Cosell once said.

Mr. Ali didn’t do deference.

“I am America. I am the part you won’t recognize,” Mr. Ali said. “But get used to me. Black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own; get used to me.”

He “made people accept him as a man, as an equal, and he was not afraid to represent himself in that way,’’ said Jim Brown, a football great who in 1967 was a among a group of black athletes who came together in the “Ali Summit” to support the boxer’s anti-war stance.

President Obama, the nation’s first black president, keeps a set of Mr. Ali’s boxing gloves on display in his study at the White House.

“He stood with King and Mandela, stood up when it was hard, spoke out when others wouldn’t,’’ the president stated after learning of Mr. Ali’s death.

“His fight outside the ring would cost him his title and his public standing. It would earn him enemies on the left and the right, make him reviled and nearly send him to jail,” stated President Obama, who is not planning to attend the service. “But Ali stood his ground. And his victory helped us get used to the America we recognize today.’’

The Rev. Al Sharpton, a longtime friend, said Mr. Ali “went from one of the most despised figures in the world to one of the most popular men in the world because people respected that he believed and sacrificed for what he believed in.’’

Mr. Ali, a one-time Baptist, could be considered the most famous convert to Islam in American history, though he later rejected Malcolm X during a power struggle within the Nation of Islam.

His battle with the government began after Mr. Ali was twice rejected for service because the draft board rated him retarded with an IQ of 78. However, under revised standards, he was declared fit for service. When he refused induction in April 1967 and was convicted of draft evasion, the World Boxing Association stripped him of his title.

He did not get his title back after the U.S. Supreme Court ruling upheld his “conscientious objector” status and was forced to start over, his boxing career having been at a standstill for nearly four years while he appealed the conviction because state boxing officials would not grant him licenses to fight.

But he put the gloves back on and would win the title back after knocking out Mr. Foreman, lose it later and briefly regain it in 1978 before losing it to Larry Holmes in 1980 at the close of his career. He retired with a record of 56 wins, including 37 knockouts, and five losses.

After Mr. Ali’s boxing career ended, he became an even more “powerful force for peace and reconciliation around the world,” President Obama stated, recalling that Mr. Ali visited sick children and those with disabilities and told them that they, too, could become the greatest.

Mr. Ali’s death held special meaning in Louisville, where he was the city’s favorite son.

Cars lined the street outside his childhood home, a bright pink single-story house that was recently renovated and turned into a museum.

Visitors piled flowers and boxing gloves around the marker designating it a historical site. They were young and old, black and white, friends and fans.

Another memorial grew outside the Muhammad Ali Center downtown, a museum built in tribute to Mr. Ali’s core values: Respect, confidence, conviction, dedication, charity, spirituality. He chose his hometown as the place for the center.

“He was a really sweet, kind, loving, giving, affectionate, wonderful person,” said his younger brother, Rahaman Ali.

Louisville Mayor Greg Fischer summed up Ali’s deep ties to the city.

‘’Muhammad Ali belongs to the world, but he only has one hometown,’’ he said. ‘’The ‘Louisville Lip’ spoke to everyone, but we heard him in a way no one else could.’’

Mr. Ali did not have to be in a boxing ring to command the world stage. In 1990, a few months after Iraq invaded Kuwait, Iraqi ruler Saddam Hussein held dozens of foreigners hostages in hopes of averting an invasion of his country. Mr. Ali flew to Baghdad, met Saddam and left with 15 American hostages.

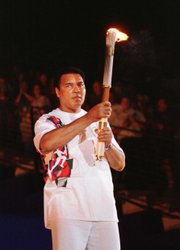

A nation that once questioned his patriotism cheered loudly in 1996 when he made a surprise appearance at the Olympic games in Atlanta, stilling the Parkinson’s tremors in his hands enough to light the Olympic flame. He also took part in the opening ceremony of the London Olympics in 2012, looking frail in a wheelchair.

In November 2002, he went to Afghanistan on a goodwill visit after being appointed a U.N. “messenger of peace.”

Mr. Ali was married four times, most recently to the former Lonnie Williams, who knew him when she was a child in Louisville. He had nine children, including daughter Laila, who became a boxer.

The diagnosis of Parkinson’s, which has been linked to head trauma, came about three years after Mr. Ali retired from boxing in 1981. He helped establish the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center at a hospital in Phoenix.

Those who knew and admired him still see him as the young man who stood up for principle.

“At a time when blacks who spoke up about injustice were labeled uppity and often arrested under one pretext or another,” basketball great Kareem Abdul-Jabbar wrote of him, “Muhammad willingly sacrificed the best years of his career to stand tall and fight for what he believed was right.

“In doing so, he made all Americans, black and white, stand taller. I may be 7’2” but I never felt taller than when standing in his shadow.”